72 KiB

+++ title = "ページングの実装" weight = 9 path = "ja/paging-implementation" date = 2019-03-14

[extra] chapter = "Memory Management" translation_based_on_commit = "27ab4518acbb132e327ed4f4f0508393e9d4d684" translators = ["woodyZootopia"] +++

この記事では私達のカーネルをページングに対応させる方法についてお伝えします。まず物理ページテーブルのフレームにカーネルがアクセスできるようにする様々な方法を示し、それらの利点と欠点について議論します。次にアドレス変換関数を、ついで新しいマッピングを作るための関数を実装します。

このブログの内容は GitHub 上で公開・開発されています。何か問題や質問などがあれば issue をたててください (訳注: リンクは原文(英語)のものになります)。またこちらにコメントを残すこともできます。この記事の完全なソースコードはpost-09 ブランチにあります。

導入

1つ前の記事ではページングの概念を説明しました。セグメンテーションと比較することによってページングのメリットを示し、ページングとページテーブルの仕組みを説明し、そしてx86_64における4層ページテーブルの設計を導入しました。ブートローダはすでにページテーブルの階層構造を設定してしまっているので、私達のカーネルは既に仮想アドレス上で動いているということを学びました。これにより、不正なメモリアクセスは、任意の物理メモリを書き換えてしまう代わりにページフォルト例外を発生させるので、安全性が向上しています。

記事の最後で、ページテーブルにカーネルからアクセスできないという問題が起きていました。この問題は、ページテーブルは物理メモリ内に格納されている一方、私達のカーネルは既に仮想アドレス上で実行されているために発生します。この記事ではその続きとして、私達のカーネルからページテーブルのフレームにアクセスするための様々な方法を探ります。それぞれの方法の利点と欠点を議論し、カーネルに採用する手法を決めます。

この方法を実装するには、ブートローダーからの補助が必要になるので、まずこれに設定を加えます。その後で、ページテーブルの階層構造を移動して、仮想アドレスを物理アドレスに変換する関数を実装します。最後に、ページテーブルに新しい対応関係を作る方法と、それを作るための未使用メモリを見つける方法を学びます。

ページテーブルにアクセスする

私達のカーネルからページテーブルにアクセスするのは案外難しいです。この問題を理解するために、前回の記事の4層ページテーブルをもう一度見てみましょう:

ここで重要なのは、それぞれのページテーブルのエントリは次のテーブルの物理アドレスであるということです。これにより、それらのアドレスに対しても変換することを避けられます。もしこの変換が行われたとしたら、性能的にも良くないですし、容易に変換の無限ループに陥りかねません。

問題は、私達のカーネル自体も仮想アドレスの上で動いているため、カーネルから直接物理アドレスにアクセスすることができないということです。例えば、アドレス4KiBにアクセスしたとき、私達は仮想アドレス4KiBにアクセスしているのであって、レベル4ページテーブルが格納されている物理アドレス4KiBにアクセスしているのではありません。物理アドレス4KiBにアクセスしたいなら、それに対応づけられている何らかの仮想アドレスを通じてのみ可能です。

そのため、ページテーブルのフレームにアクセスするためには、どこかの仮想ページをそれに対応づけなければいけません。このような、任意のページテーブルのフレームにアクセスできるようにしてくれる対応付けを作る方法にはいくつかあります。

恒等対応

シンプルな方法として、すべてのページテーブルを恒等対応させるということが考えられるでしょう:

この例では、いくつかの恒等対応したページテーブルのフレームが見てとれます。こうすることで、ページテーブルの物理アドレスは仮想アドレスとしても正当になり、よってCR3レジスタから始めることで全てのレベルのページテーブルに簡単にアクセスできます。

しかし、この方法では仮想アドレス空間が散らかってしまい、より大きいサイズの連続したメモリを見つけることが難しくなります。例えば、上の図において、ファイルをメモリにマップするために1000KiBの大きさの仮想メモリ領域を作りたいとします。28KiBを始点として領域を作ろうとすると、1004KiBのところで既存のページと衝突してしまうのでうまくいきません。そのため、1008KiBのような、十分な広さで対応付けのない領域が見つかるまで更に探さないといけません。これはセグメンテーションの時に見た断片化の問題に似ています。

同様に、新しいページテーブルを作ることもずっと難しくなります。なぜなら、対応するページがまだ使われていない物理フレームを見つけないといけないからです。例えば、メモリマップトファイルのために1008KiBから1000KiBにわたって仮想メモリを占有したとしましょう。すると、すると、物理アドレス1000KiBから2008KiBまでのフレームは、もう恒等対応を作ることができないので、使用することができません。

固定オフセットの対応づけ

仮想アドレス空間を散らかしてしまうという問題を回避するために、ページテーブルの対応づけのために別のメモリ領域を使うことができます。ページテーブルを恒等対応させる代わりに、仮想アドレス空間で一定のオフセットをおいて対応づけてみましょう。例えば、オフセットを10TiBにしてみましょう:

10TiBから10TiB+物理メモリ全体の大きさの範囲の仮想メモリをページテーブルの対応付け専用に使うことで、恒等対応のときに存在していた衝突問題を回避しています。このように巨大な領域を仮想アドレス空間内に用意するのは、仮想アドレス空間が物理メモリの大きさより遥かに大きい場合にのみ可能です。x86_64で用いられている48bit(仮想)アドレス空間は256TiBもの大きさがあるので、これは問題ではありません。

この方法では、新しいページテーブルを作るたびに新しい対応付けを作る必要があるという欠点があります。また、他のアドレス空間のページテーブルにアクセスすることができると、新しいプロセスを作るときに便利なのですがこれも不可能です。

物理メモリ全体を対応付ける

これらの問題はページテーブルのフレームだけと言わず物理メモリ全体を対応付けてしまえば解決します:

この方法を使えば、私達のカーネルは他のアドレス空間を含め任意の物理メモリにアクセスできます。用意する仮想メモリの範囲は以前と同じであり、違うのは全てのページが対応付けられているということです。

この方法の欠点は、物理メモリへの対応付けを格納するために、追加でページテーブルが必要になるところです。これらのページテーブルもどこかに格納されなければならず、したがって物理メモリの一部を占有することになります。これはメモリの量が少ないデバイスにおいては問題となりえます。

しかし、x86_64においては、通常の4KiBサイズのページに代わって、大きさ2MiBのhuge pagesを対応付けに使うことができます。こうすれば、例えば32GiBの物理メモリを対応付けるのに、レベル3テーブル1個とレベル2テーブル32個があればいいので、たったの132KiBしか必要ではありません。huge pagesは、トランスレーション・ルックアサイド・バッファ (TLB) のエントリをあまり使わないので、キャッシュ的にも効率が良いです。

一時的な対応関係

物理メモリの量が非常に限られたデバイスについては、アクセスする必要があるときだけページテーブルのフレームを一時的に対応づけるという方法が考えられます。そのような一時的な対応を作りたいときには、たった一つだけ恒等対応させられたレベル1テーブルがあれば良いです:

この図におけるレベル1テーブルは仮想アドレス空間の最初の2MiBを制御しています。なぜなら、このテーブルにはCR3レジスタから始めて、レベル4、3、2のページテーブルの0番目のエントリを辿ることで到達できるからです。8番目のエントリは、アドレス32 KiBの仮想アドレスページをアドレス32 KiBの物理アドレスページに対応付けるので、レベル1テーブル自体を恒等対応させています。この図ではその恒等対応を32 KiBのところの横向きの(茶色の)矢印で表しています。

恒等対応させたレベル1テーブルに書き込むことによって、カーネルは最大511個の一時的な対応を作ることができます(512から、恒等対応に必要な1つを除く)。上の例では、カーネルは2つの一時的な対応を作りました:

- レベル1テーブルの0番目のエントリをアドレス

24 KiBのフレームに対応付けることで、破線の矢印で示されているように0 KiBの仮想ページからレベル2ページテーブルの物理フレームへの一時的対応付けを行いました。 - レベル1テーブルの9番目のエントリをアドレス

4 KiBのフレームに対応付けることで、破線の矢印で示されているように36 KiBの仮想ページからレベル4ページテーブルの物理フレームへの一時的対応付を行いました。

これで、カーネルは0 KiBに書き込むことによってレベル2ページテーブルに、36 KiBに書き込むことによってレベル4ページテーブルにアクセスできるようになりました。

任意のページテーブルに一時的対応付けを用いてアクセスする手続きは以下のようになるでしょう:

- 恒等対応しているレベル1テーブルのうち、使われていないエントリを探す。

- そのエントリを私達のアクセスしたいページテーブルの物理フレームに対応付ける。

- そのエントリに対応付けられている仮想ページを通じて、対象のフレームにアクセスする。

- エントリを未使用に戻すことで、一時的対応付けを削除する。

この方法では、同じ512個の下層ページを対応付けを作成するために再利用するため、物理メモリは4KiBしか必要としません。欠点としては、やや面倒であるということが言えるでしょう。特に、新しい対応付けを作る際に複数のページテーブルの変更が必要になるかもしれず、上の手続きを複数回繰り返さなくてはならないかもしれません。

再帰的ページテーブル

他に興味深いアプローチとして、再帰的にページテーブルを対応付ける方法があり、この方法では追加のページテーブルは一切不要です。発想としては、レベル4ページテーブルのエントリのどれかをレベル4ページテーブル自体に対応付けるのです。こうすることにより、仮想アドレス空間の一部を予約しておき、現在及び将来のあらゆるページテーブルフレームをその空間に対応付けているのと同じことになります。

これがうまく行く理由を説明するために、例を見てみましょう:

この記事の最初での例との唯一の違いは、レベル4テーブルの511番目に、物理フレーム4 KiBすなわちレベル4テーブル自体のフレームに対応付けられたエントリが追加されていることです。

CPUにこのエントリを辿らせるようにすると、レベル3テーブルではなく、そのレベル4テーブルに再び到達します。これは再帰的関数(自らを呼び出す関数)に似ているので、再帰的ページテーブルと呼ばれます。レベル4テーブルのすべてのエントリはレベル3テーブルを指しているとCPUは思っているので、CPUはいまレベル4テーブルをレベル3テーブルとして扱っているということに注目してください。これがうまく行くのは、x86_64においてはすべてのレベルのテーブルが全く同じレイアウトを持っているためです。

実際に変換を始める前に、この再帰エントリを1回以上たどることで、CPUのたどる階層の数を短くできます。例えば、一度再帰的エントリを辿ったあとでレベル3テーブルに進むと、CPUはレベル3テーブルをレベル2テーブルだと思い込みます。同様に、レベル2テーブルをレベル1テーブルだと、レベル1テーブルを対応付けられた(物理)フレームだと思います。CPUがこれを物理フレームだと思っているということは、レベル1ページテーブルを読み書きできるということを意味します。下の図はこの5回の変換ステップを示しています:

同様に、変換の前に再帰エントリを2回たどることで、階層移動の回数を2回に減らせます:

ステップごとにこれを見てみましょう:まず、CPUはレベル4テーブルの再帰エントリをたどり、レベル3テーブルに着いたと思い込みます。同じ再帰エントリを再びたどり、レベル2テーブルに着いたと考えます。しかし実際にはまだレベル4テーブルから動いていません。CPUが異なるエントリをたどると、レベル3テーブルに到着するのですが、CPUはレベル1にすでにいるのだと思っています。そのため、次のエントリはレベル2テーブルを指しているのですが、CPUは対応付けられた物理フレームを指していると思うので、私達はレベル2テーブルを読み書きできるというわけです。

レベル3や4のテーブルにアクセスするのも同じやり方でできます。レベル3テーブルにアクセスするためには、再帰エントリを3回たどることでCPUを騙し、すでにレベル1テーブルにいると思い込ませます。そこで別のエントリをたどりレベル3テーブルに着くと、CPUはそれを対応付けられたフレームとして扱います。レベル4テーブル自体にアクセスするには、再帰エントリを4回辿ればCPUはそのレベル4テーブル自体を対応付けられたフレームとして扱ってくれるというわけです(下の青紫の矢印)。

この概念を理解するのは難しいかもしれませんが、実際これは非常にうまく行くのです。

下のセクションでは、再帰エントリをたどるための仮想アドレスを構成する方法について説明します。私達の(カーネルの)実装には再帰的ページングは使わないので、これを読まずに記事の続きを読み進めても構いません。もし興味がおありでしたら、下の「アドレス計算」をクリックして展開してください。

アドレス計算

We saw that we can access tables of all levels by following the recursive entry once or multiple times before the actual translation. Since the indexes into the tables of the four levels are derived directly from the virtual address, we need to construct special virtual addresses for this technique. Remember, the page table indexes are derived from the address in the following way:

Let's assume that we want to access the level 1 page table that maps a specific page. As we learned above, this means that we have to follow the recursive entry one time before continuing with the level 4, level 3, and level 2 indexes. To do that we move each block of the address one block to the right and set the original level 4 index to the index of the recursive entry:

For accessing the level 2 table of that page, we move each index block two blocks to the right and set both the blocks of the original level 4 index and the original level 3 index to the index of the recursive entry:

Accessing the level 3 table works by moving each block three blocks to the right and using the recursive index for the original level 4, level 3, and level 2 address blocks:

Finally, we can access the level 4 table by moving each block four blocks to the right and using the recursive index for all address blocks except for the offset:

We can now calculate virtual addresses for the page tables of all four levels. We can even calculate an address that points exactly to a specific page table entry by multiplying its index by 8, the size of a page table entry.

The table below summarizes the address structure for accessing the different kinds of frames:

| Virtual Address for | Address Structure (octal) |

|---|---|

| Page | 0o_SSSSSS_AAA_BBB_CCC_DDD_EEEE |

| Level 1 Table Entry | 0o_SSSSSS_RRR_AAA_BBB_CCC_DDDD |

| Level 2 Table Entry | 0o_SSSSSS_RRR_RRR_AAA_BBB_CCCC |

| Level 3 Table Entry | 0o_SSSSSS_RRR_RRR_RRR_AAA_BBBB |

| Level 4 Table Entry | 0o_SSSSSS_RRR_RRR_RRR_RRR_AAAA |

Whereas AAA is the level 4 index, BBB the level 3 index, CCC the level 2 index, and DDD the level 1 index of the mapped frame, and EEEE the offset into it. RRR is the index of the recursive entry. When an index (three digits) is transformed to an offset (four digits), it is done by multiplying it by 8 (the size of a page table entry). With this offset, the resulting address directly points to the respective page table entry.

SSSSSS are sign extension bits, which means that they are all copies of bit 47. This is a special requirement for valid addresses on the x86_64 architecture. We explained it in the previous post.

We use octal numbers for representing the addresses since each octal character represents three bits, which allows us to clearly separate the 9-bit indexes of the different page table levels. This isn't possible with the hexadecimal system where each character represents four bits.

In Rust Code

To construct such addresses in Rust code, you can use bitwise operations:

// the virtual address whose corresponding page tables you want to access

let addr: usize = […];

let r = 0o777; // recursive index

let sign = 0o177777 << 48; // sign extension

// retrieve the page table indices of the address that we want to translate

let l4_idx = (addr >> 39) & 0o777; // level 4 index

let l3_idx = (addr >> 30) & 0o777; // level 3 index

let l2_idx = (addr >> 21) & 0o777; // level 2 index

let l1_idx = (addr >> 12) & 0o777; // level 1 index

let page_offset = addr & 0o7777;

// calculate the table addresses

let level_4_table_addr =

sign | (r << 39) | (r << 30) | (r << 21) | (r << 12);

let level_3_table_addr =

sign | (r << 39) | (r << 30) | (r << 21) | (l4_idx << 12);

let level_2_table_addr =

sign | (r << 39) | (r << 30) | (l4_idx << 21) | (l3_idx << 12);

let level_1_table_addr =

sign | (r << 39) | (l4_idx << 30) | (l3_idx << 21) | (l2_idx << 12);

The above code assumes that the last level 4 entry with index 0o777 (511) is recursively mapped. This isn't the case currently, so the code won't work yet. See below on how to tell the bootloader to set up the recursive mapping.

Alternatively to performing the bitwise operations by hand, you can use the RecursivePageTable type of the x86_64 crate, which provides safe abstractions for various page table operations. For example, the code below shows how to translate a virtual address to its mapped physical address:

// in src/memory.rs

use x86_64::structures::paging::{Mapper, Page, PageTable, RecursivePageTable};

use x86_64::{VirtAddr, PhysAddr};

/// Creates a RecursivePageTable instance from the level 4 address.

let level_4_table_addr = […];

let level_4_table_ptr = level_4_table_addr as *mut PageTable;

let recursive_page_table = unsafe {

let level_4_table = &mut *level_4_table_ptr;

RecursivePageTable::new(level_4_table).unwrap();

}

/// Retrieve the physical address for the given virtual address

let addr: u64 = […]

let addr = VirtAddr::new(addr);

let page: Page = Page::containing_address(addr);

// perform the translation

let frame = recursive_page_table.translate_page(page);

frame.map(|frame| frame.start_address() + u64::from(addr.page_offset()))

Again, a valid recursive mapping is required for this code. With such a mapping, the missing level_4_table_addr can be calculated as in the first code example.

Recursive Paging is an interesting technique that shows how powerful a single mapping in a page table can be. It is relatively easy to implement and only requires a minimal amount of setup (just a single recursive entry), so it's a good choice for first experiments with paging.

However, it also has some disadvantages:

- It occupies a large amount of virtual memory (512GiB). This isn't a big problem in the large 48-bit address space, but it might lead to suboptimal cache behavior.

- It only allows accessing the currently active address space easily. Accessing other address spaces is still possible by changing the recursive entry, but a temporary mapping is required for switching back. We described how to do this in the (outdated) Remap The Kernel post.

- It heavily relies on the page table format of x86 and might not work on other architectures.

Bootloader Support

All of these approaches require page table modifications for their setup. For example, mappings for the physical memory need to be created or an entry of the level 4 table needs to be mapped recursively. The problem is that we can't create these required mappings without an existing way to access the page tables.

This means that we need the help of the bootloader, which creates the page tables that our kernel runs on. The bootloader has access to the page tables, so it can create any mappings that we need. In its current implementation, the bootloader crate has support for two of the above approaches, controlled through cargo features:

- The

map_physical_memoryfeature maps the complete physical memory somewhere into the virtual address space. Thus, the kernel can access all physical memory and can follow the Map the Complete Physical Memory approach. - With the

recursive_page_tablefeature, the bootloader maps an entry of the level 4 page table recursively. This allows the kernel to access the page tables as described in the Recursive Page Tables section.

We choose the first approach for our kernel since it is simple, platform-independent, and more powerful (it also allows access to non-page-table-frames). To enable the required bootloader support, we add the map_physical_memory feature to our bootloader dependency:

[dependencies]

bootloader = { version = "0.9.8", features = ["map_physical_memory"]}

With this feature enabled, the bootloader maps the complete physical memory to some unused virtual address range. To communicate the virtual address range to our kernel, the bootloader passes a boot information structure.

Boot Information

The bootloader crate defines a BootInfo struct that contains all the information it passes to our kernel. The struct is still in an early stage, so expect some breakage when updating to future semver-incompatible bootloader versions. With the map_physical_memory feature enabled, it currently has the two fields memory_map and physical_memory_offset:

- The

memory_mapfield contains an overview of the available physical memory. This tells our kernel how much physical memory is available in the system and which memory regions are reserved for devices such as the VGA hardware. The memory map can be queried from the BIOS or UEFI firmware, but only very early in the boot process. For this reason, it must be provided by the bootloader because there is no way for the kernel to retrieve it later. We will need the memory map later in this post. - The

physical_memory_offsettells us the virtual start address of the physical memory mapping. By adding this offset to a physical address, we get the corresponding virtual address. This allows us to access arbitrary physical memory from our kernel.

The bootloader passes the BootInfo struct to our kernel in the form of a &'static BootInfo argument to our _start function. We don't have this argument declared in our function yet, so let's add it:

// in src/main.rs

use bootloader::BootInfo;

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn _start(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! { // new argument

[…]

}

It wasn't a problem to leave off this argument before because the x86_64 calling convention passes the first argument in a CPU register. Thus, the argument is simply ignored when it isn't declared. However, it would be a problem if we accidentally used a wrong argument type, since the compiler doesn't know the correct type signature of our entry point function.

The entry_point Macro

Since our _start function is called externally from the bootloader, no checking of our function signature occurs. This means that we could let it take arbitrary arguments without any compilation errors, but it would fail or cause undefined behavior at runtime.

To make sure that the entry point function has always the correct signature that the bootloader expects, the bootloader crate provides an entry_point macro that provides a type-checked way to define a Rust function as the entry point. Let's rewrite our entry point function to use this macro:

// in src/main.rs

use bootloader::{BootInfo, entry_point};

entry_point!(kernel_main);

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

[…]

}

We no longer need to use extern "C" or no_mangle for our entry point, as the macro defines the real lower level _start entry point for us. The kernel_main function is now a completely normal Rust function, so we can choose an arbitrary name for it. The important thing is that it is type-checked so that a compilation error occurs when we use a wrong function signature, for example by adding an argument or changing the argument type.

Let's perform the same change in our lib.rs:

// in src/lib.rs

#[cfg(test)]

use bootloader::{entry_point, BootInfo};

#[cfg(test)]

entry_point!(test_kernel_main);

/// Entry point for `cargo test`

#[cfg(test)]

fn test_kernel_main(_boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// like before

init();

test_main();

hlt_loop();

}

Since the entry point is only used in test mode, we add the #[cfg(test)] attribute to all items. We give our test entry point the distinct name test_kernel_main to avoid confusion with the kernel_main of our main.rs. We don't use the BootInfo parameter for now, so we prefix the parameter name with a _ to silence the unused variable warning.

Implementation

Now that we have access to physical memory, we can finally start to implement our page table code. First, we will take a look at the currently active page tables that our kernel runs on. In the second step, we will create a translation function that returns the physical address that a given virtual address is mapped to. As the last step, we will try to modify the page tables in order to create a new mapping.

Before we begin, we create a new memory module for our code:

// in src/lib.rs

pub mod memory;

For the module we create an empty src/memory.rs file.

Accessing the Page Tables

At the end of the previous post, we tried to take a look at the page tables our kernel runs on, but failed since we couldn't access the physical frame that the CR3 register points to. We're now able to continue from there by creating an active_level_4_table function that returns a reference to the active level 4 page table:

// in src/memory.rs

use x86_64::{

structures::paging::PageTable,

VirtAddr,

};

/// Returns a mutable reference to the active level 4 table.

///

/// This function is unsafe because the caller must guarantee that the

/// complete physical memory is mapped to virtual memory at the passed

/// `physical_memory_offset`. Also, this function must be only called once

/// to avoid aliasing `&mut` references (which is undefined behavior).

pub unsafe fn active_level_4_table(physical_memory_offset: VirtAddr)

-> &'static mut PageTable

{

use x86_64::registers::control::Cr3;

let (level_4_table_frame, _) = Cr3::read();

let phys = level_4_table_frame.start_address();

let virt = physical_memory_offset + phys.as_u64();

let page_table_ptr: *mut PageTable = virt.as_mut_ptr();

&mut *page_table_ptr // unsafe

}

First, we read the physical frame of the active level 4 table from the CR3 register. We then take its physical start address, convert it to an u64, and add it to physical_memory_offset to get the virtual address where the page table frame is mapped. Finally, we convert the virtual address to a *mut PageTable raw pointer through the as_mut_ptr method and then unsafely create a &mut PageTable reference from it. We create a &mut reference instead of a & reference because we will mutate the page tables later in this post.

We don't need to use an unsafe block here because Rust treats the complete body of an unsafe fn like a large unsafe block. This makes our code more dangerous since we could accidentally introduce an unsafe operation in previous lines without noticing. It also makes it much more difficult to spot the unsafe operations. There is an RFC to change this behavior.

We can now use this function to print the entries of the level 4 table:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

use blog_os::memory::active_level_4_table;

use x86_64::VirtAddr;

println!("Hello World{}", "!");

blog_os::init();

let phys_mem_offset = VirtAddr::new(boot_info.physical_memory_offset);

let l4_table = unsafe { active_level_4_table(phys_mem_offset) };

for (i, entry) in l4_table.iter().enumerate() {

if !entry.is_unused() {

println!("L4 Entry {}: {:?}", i, entry);

}

}

// as before

#[cfg(test)]

test_main();

println!("It did not crash!");

blog_os::hlt_loop();

}

First, we convert the physical_memory_offset of the BootInfo struct to a VirtAddr and pass it to the active_level_4_table function. We then use the iter function to iterate over the page table entries and the enumerate combinator to additionally add an index i to each element. We only print non-empty entries because all 512 entries wouldn't fit on the screen.

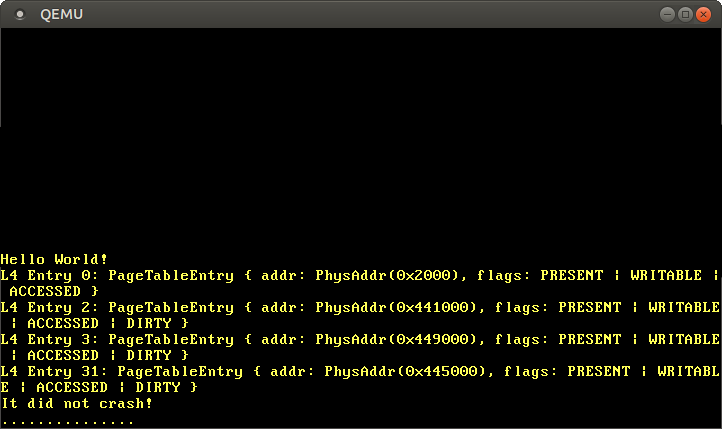

When we run it, we see the following output:

We see that there are various non-empty entries, which all map to different level 3 tables. There are so many regions because kernel code, kernel stack, the physical memory mapping, and the boot information all use separate memory areas.

To traverse the page tables further and take a look at a level 3 table, we can take the mapped frame of an entry convert it to a virtual address again:

// in the `for` loop in src/main.rs

use x86_64::structures::paging::PageTable;

if !entry.is_unused() {

println!("L4 Entry {}: {:?}", i, entry);

// get the physical address from the entry and convert it

let phys = entry.frame().unwrap().start_address();

let virt = phys.as_u64() + boot_info.physical_memory_offset;

let ptr = VirtAddr::new(virt).as_mut_ptr();

let l3_table: &PageTable = unsafe { &*ptr };

// print non-empty entries of the level 3 table

for (i, entry) in l3_table.iter().enumerate() {

if !entry.is_unused() {

println!(" L3 Entry {}: {:?}", i, entry);

}

}

}

For looking at the level 2 and level 1 tables, we repeat that process for the level 3 and level 2 entries. As you can imagine, this gets very verbose quickly, so we don't show the full code here.

Traversing the page tables manually is interesting because it helps to understand how the CPU performs the translation. However, most of the time we are only interested in the mapped physical address for a given virtual address, so let's create a function for that.

Translating Addresses

For translating a virtual to a physical address, we have to traverse the four-level page table until we reach the mapped frame. Let's create a function that performs this translation:

// in src/memory.rs

use x86_64::PhysAddr;

/// Translates the given virtual address to the mapped physical address, or

/// `None` if the address is not mapped.

///

/// This function is unsafe because the caller must guarantee that the

/// complete physical memory is mapped to virtual memory at the passed

/// `physical_memory_offset`.

pub unsafe fn translate_addr(addr: VirtAddr, physical_memory_offset: VirtAddr)

-> Option<PhysAddr>

{

translate_addr_inner(addr, physical_memory_offset)

}

We forward the function to a safe translate_addr_inner function to limit the scope of unsafe. As we noted above, Rust treats the complete body of an unsafe fn like a large unsafe block. By calling into a private safe function, we make each unsafe operation explicit again.

The private inner function contains the real implementation:

// in src/memory.rs

/// Private function that is called by `translate_addr`.

///

/// This function is safe to limit the scope of `unsafe` because Rust treats

/// the whole body of unsafe functions as an unsafe block. This function must

/// only be reachable through `unsafe fn` from outside of this module.

fn translate_addr_inner(addr: VirtAddr, physical_memory_offset: VirtAddr)

-> Option<PhysAddr>

{

use x86_64::structures::paging::page_table::FrameError;

use x86_64::registers::control::Cr3;

// read the active level 4 frame from the CR3 register

let (level_4_table_frame, _) = Cr3::read();

let table_indexes = [

addr.p4_index(), addr.p3_index(), addr.p2_index(), addr.p1_index()

];

let mut frame = level_4_table_frame;

// traverse the multi-level page table

for &index in &table_indexes {

// convert the frame into a page table reference

let virt = physical_memory_offset + frame.start_address().as_u64();

let table_ptr: *const PageTable = virt.as_ptr();

let table = unsafe {&*table_ptr};

// read the page table entry and update `frame`

let entry = &table[index];

frame = match entry.frame() {

Ok(frame) => frame,

Err(FrameError::FrameNotPresent) => return None,

Err(FrameError::HugeFrame) => panic!("huge pages not supported"),

};

}

// calculate the physical address by adding the page offset

Some(frame.start_address() + u64::from(addr.page_offset()))

}

Instead of reusing our active_level_4_table function, we read the level 4 frame from the CR3 register again. We do this because it simplifies this prototype implementation. Don't worry, we will create a better solution in a moment.

The VirtAddr struct already provides methods to compute the indexes into the page tables of the four levels. We store these indexes in a small array because it allows us to traverse the page tables using a for loop. Outside of the loop, we remember the last visited frame to calculate the physical address later. The frame points to page table frames while iterating, and to the mapped frame after the last iteration, i.e. after following the level 1 entry.

Inside the loop, we again use the physical_memory_offset to convert the frame into a page table reference. We then read the entry of the current page table and use the PageTableEntry::frame function to retrieve the mapped frame. If the entry is not mapped to a frame we return None. If the entry maps a huge 2MiB or 1GiB page we panic for now.

Let's test our translation function by translating some addresses:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// new import

use blog_os::memory::translate_addr;

[…] // hello world and blog_os::init

let phys_mem_offset = VirtAddr::new(boot_info.physical_memory_offset);

let addresses = [

// the identity-mapped vga buffer page

0xb8000,

// some code page

0x201008,

// some stack page

0x0100_0020_1a10,

// virtual address mapped to physical address 0

boot_info.physical_memory_offset,

];

for &address in &addresses {

let virt = VirtAddr::new(address);

let phys = unsafe { translate_addr(virt, phys_mem_offset) };

println!("{:?} -> {:?}", virt, phys);

}

[…] // test_main(), "it did not crash" printing, and hlt_loop()

}

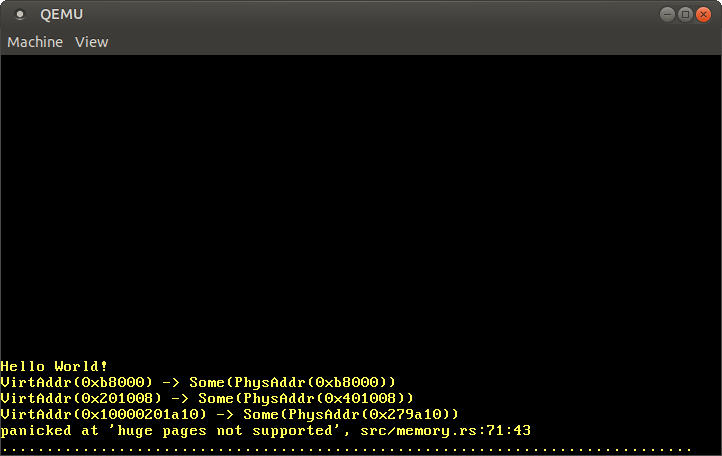

When we run it, we see the following output:

As expected, the identity-mapped address 0xb8000 translates to the same physical address. The code page and the stack page translate to some arbitrary physical addresses, which depend on how the bootloader created the initial mapping for our kernel. It's worth noting that the last 12 bits always stay the same after translation, which makes sense because these bits are the page offset and not part of the translation.

Since each physical address can be accessed by adding the physical_memory_offset, the translation of the physical_memory_offset address itself should point to physical address 0. However, the translation fails because the mapping uses huge pages for efficiency, which is not supported in our implementation yet.

Using OffsetPageTable

Translating virtual to physical addresses is a common task in an OS kernel, therefore the x86_64 crate provides an abstraction for it. The implementation already supports huge pages and several other page table functions apart from translate_addr, so we will use it in the following instead of adding huge page support to our own implementation.

The base of the abstraction are two traits that define various page table mapping functions:

- The

Mappertrait is generic over the page size and provides functions that operate on pages. Examples aretranslate_page, which translates a given page to a frame of the same size, andmap_to, which creates a new mapping in the page table. - The

Translatetrait provides functions that work with multiple page sizes such astranslate_addror the generaltranslate.

The traits only define the interface, they don't provide any implementation. The x86_64 crate currently provides three types that implement the traits with different requirements. The OffsetPageTable type assumes that the complete physical memory is mapped to the virtual address space at some offset. The MappedPageTable is a bit more flexible: It only requires that each page table frame is mapped to the virtual address space at a calculable address. Finally, the RecursivePageTable type can be used to access page table frames through recursive page tables.

In our case, the bootloader maps the complete physical memory at a virtual address specified by the physical_memory_offset variable, so we can use the OffsetPageTable type. To initialize it, we create a new init function in our memory module:

use x86_64::structures::paging::OffsetPageTable;

/// Initialize a new OffsetPageTable.

///

/// This function is unsafe because the caller must guarantee that the

/// complete physical memory is mapped to virtual memory at the passed

/// `physical_memory_offset`. Also, this function must be only called once

/// to avoid aliasing `&mut` references (which is undefined behavior).

pub unsafe fn init(physical_memory_offset: VirtAddr) -> OffsetPageTable<'static> {

let level_4_table = active_level_4_table(physical_memory_offset);

OffsetPageTable::new(level_4_table, physical_memory_offset)

}

// make private

unsafe fn active_level_4_table(physical_memory_offset: VirtAddr)

-> &'static mut PageTable

{…}

The function takes the physical_memory_offset as an argument and returns a new OffsetPageTable instance with a 'static lifetime. This means that the instance stays valid for the complete runtime of our kernel. In the function body, we first call the active_level_4_table function to retrieve a mutable reference to the level 4 page table. We then invoke the OffsetPageTable::new function with this reference. As the second parameter, the new function expects the virtual address at which the mapping of the physical memory starts, which is given in the physical_memory_offset variable.

The active_level_4_table function should be only called from the init function from now on because it can easily lead to aliased mutable references when called multiple times, which can cause undefined behavior. For this reason, we make the function private by removing the pub specifier.

We now can use the Translate::translate_addr method instead of our own memory::translate_addr function. We only need to change a few lines in our kernel_main:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// new: different imports

use blog_os::memory;

use x86_64::{structures::paging::Translate, VirtAddr};

[…] // hello world and blog_os::init

let phys_mem_offset = VirtAddr::new(boot_info.physical_memory_offset);

// new: initialize a mapper

let mapper = unsafe { memory::init(phys_mem_offset) };

let addresses = […]; // same as before

for &address in &addresses {

let virt = VirtAddr::new(address);

// new: use the `mapper.translate_addr` method

let phys = mapper.translate_addr(virt);

println!("{:?} -> {:?}", virt, phys);

}

[…] // test_main(), "it did not crash" printing, and hlt_loop()

}

We need to import the Translate trait in order to use the translate_addr method it provides.

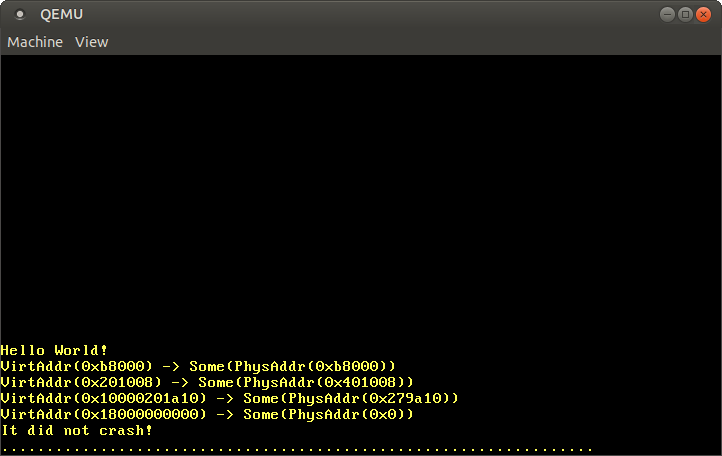

When we run it now, we see the same translation results as before, with the difference that the huge page translation now also works:

As expected, the translations of 0xb8000 and the code and stack addresses stay the same as with our own translation function. Additionally, we now see that the virtual address physical_memory_offset is mapped to the physical address 0x0.

By using the translation function of the MappedPageTable type we can spare ourselves the work of implementing huge page support. We also have access to other page functions such as map_to, which we will use in the next section.

At this point we no longer need our memory::translate_addr and memory::translate_addr_inner functions, so we can delete them.

Creating a new Mapping

Until now we only looked at the page tables without modifying anything. Let's change that by creating a new mapping for a previously unmapped page.

We will use the map_to function of the Mapper trait for our implementation, so let's take a look at that function first. The documentation tells us that it takes four arguments: the page that we want to map, the frame that the page should be mapped to, a set of flags for the page table entry, and a frame_allocator. The frame allocator is needed because mapping the given page might require creating additional page tables, which need unused frames as backing storage.

A create_example_mapping Function

The first step of our implementation is to create a new create_example_mapping function that maps a given virtual page to 0xb8000, the physical frame of the VGA text buffer. We choose that frame because it allows us to easily test if the mapping was created correctly: We just need to write to the newly mapped page and see whether we see the write appear on the screen.

The create_example_mapping function looks like this:

// in src/memory.rs

use x86_64::{

PhysAddr,

structures::paging::{Page, PhysFrame, Mapper, Size4KiB, FrameAllocator}

};

/// Creates an example mapping for the given page to frame `0xb8000`.

pub fn create_example_mapping(

page: Page,

mapper: &mut OffsetPageTable,

frame_allocator: &mut impl FrameAllocator<Size4KiB>,

) {

use x86_64::structures::paging::PageTableFlags as Flags;

let frame = PhysFrame::containing_address(PhysAddr::new(0xb8000));

let flags = Flags::PRESENT | Flags::WRITABLE;

let map_to_result = unsafe {

// FIXME: this is not safe, we do it only for testing

mapper.map_to(page, frame, flags, frame_allocator)

};

map_to_result.expect("map_to failed").flush();

}

In addition to the page that should be mapped, the function expects a mutable reference to an OffsetPageTable instance and a frame_allocator. The frame_allocator parameter uses the impl Trait syntax to be generic over all types that implement the FrameAllocator trait. The trait is generic over the PageSize trait to work with both standard 4KiB pages and huge 2MiB/1GiB pages. We only want to create a 4KiB mapping, so we set the generic parameter to Size4KiB.

The map_to method is unsafe because the caller must ensure that the frame is not already in use. The reason for this is that mapping the same frame twice could result in undefined behavior, for example when two different &mut references point to the same physical memory location. In our case, we reuse the VGA text buffer frame, which is already mapped, so we break the required condition. However, the create_example_mapping function is only a temporary testing function and will be removed after this post, so it is ok. To remind us of the unsafety, we put a FIXME comment on the line.

In addition to the page and the unused_frame, the map_to method takes a set of flags for the mapping and a reference to the frame_allocator, which will be explained in a moment. For the flags, we set the PRESENT flag because it is required for all valid entries and the WRITABLE flag to make the mapped page writable. For a list of all possible flags, see the Page Table Format section of the previous post.

The map_to function can fail, so it returns a Result. Since this is just some example code that does not need to be robust, we just use expect to panic when an error occurs. On success, the function returns a MapperFlush type that provides an easy way to flush the newly mapped page from the translation lookaside buffer (TLB) with its flush method. Like Result, the type uses the #[must_use] attribute to emit a warning when we accidentally forget to use it.

A dummy FrameAllocator

To be able to call create_example_mapping we need to create a type that implements the FrameAllocator trait first. As noted above, the trait is responsible for allocating frames for new page table if they are needed by map_to.

Let's start with the simple case and assume that we don't need to create new page tables. For this case, a frame allocator that always returns None suffices. We create such an EmptyFrameAllocator for testing our mapping function:

// in src/memory.rs

/// A FrameAllocator that always returns `None`.

pub struct EmptyFrameAllocator;

unsafe impl FrameAllocator<Size4KiB> for EmptyFrameAllocator {

fn allocate_frame(&mut self) -> Option<PhysFrame> {

None

}

}

Implementing the FrameAllocator is unsafe because the implementer must guarantee that the allocator yields only unused frames. Otherwise undefined behavior might occur, for example when two virtual pages are mapped to the same physical frame. Our EmptyFrameAllocator only returns None, so this isn't a problem in this case.

Choosing a Virtual Page

We now have a simple frame allocator that we can pass to our create_example_mapping function. However, the allocator always returns None, so this will only work if no additional page table frames are needed for creating the mapping. To understand when additional page table frames are needed and when not, let's consider an example:

The graphic shows the virtual address space on the left, the physical address space on the right, and the page tables in between. The page tables are stored in physical memory frames, indicated by the dashed lines. The virtual address space contains a single mapped page at address 0x803fe00000, marked in blue. To translate this page to its frame, the CPU walks the 4-level page table until it reaches the frame at address 36 KiB.

Additionally, the graphic shows the physical frame of the VGA text buffer in red. Our goal is to map a previously unmapped virtual page to this frame using our create_example_mapping function. Since our EmptyFrameAllocator always returns None, we want to create the mapping so that no additional frames are needed from the allocator. This depends on the virtual page that we select for the mapping.

The graphic shows two candidate pages in the virtual address space, both marked in yellow. One page is at address 0x803fdfd000, which is 3 pages before the mapped page (in blue). While the level 4 and level 3 page table indices are the same as for the blue page, the level 2 and level 1 indices are different (see the previous post). The different index into the level 2 table means that a different level 1 table is used for this page. Since this level 1 table does not exist yet, we would need to create it if we chose that page for our example mapping, which would require an additional unused physical frame. In contrast, the second candidate page at address 0x803fe02000 does not have this problem because it uses the same level 1 page table than the blue page. Thus, all required page tables already exist.

In summary, the difficulty of creating a new mapping depends on the virtual page that we want to map. In the easiest case, the level 1 page table for the page already exists and we just need to write a single entry. In the most difficult case, the page is in a memory region for that no level 3 exists yet so that we need to create new level 3, level 2 and level 1 page tables first.

For calling our create_example_mapping function with the EmptyFrameAllocator, we need to choose a page for that all page tables already exist. To find such a page, we can utilize the fact that the bootloader loads itself in the first megabyte of the virtual address space. This means that a valid level 1 table exists for all pages this region. Thus, we can choose any unused page in this memory region for our example mapping, such as the page at address 0. Normally, this page should stay unused to guarantee that dereferencing a null pointer causes a page fault, so we know that the bootloader leaves it unmapped.

Creating the Mapping

We now have all the required parameters for calling our create_example_mapping function, so let's modify our kernel_main function to map the page at virtual address 0. Since we map the page to the frame of the VGA text buffer, we should be able to write to the screen through it afterwards. The implementation looks like this:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

use blog_os::memory;

use x86_64::{structures::paging::Page, VirtAddr}; // new import

[…] // hello world and blog_os::init

let phys_mem_offset = VirtAddr::new(boot_info.physical_memory_offset);

let mut mapper = unsafe { memory::init(phys_mem_offset) };

let mut frame_allocator = memory::EmptyFrameAllocator;

// map an unused page

let page = Page::containing_address(VirtAddr::new(0));

memory::create_example_mapping(page, &mut mapper, &mut frame_allocator);

// write the string `New!` to the screen through the new mapping

let page_ptr: *mut u64 = page.start_address().as_mut_ptr();

unsafe { page_ptr.offset(400).write_volatile(0x_f021_f077_f065_f04e)};

[…] // test_main(), "it did not crash" printing, and hlt_loop()

}

We first create the mapping for the page at address 0 by calling our create_example_mapping function with a mutable reference to the mapper and the frame_allocator instances. This maps the page to the VGA text buffer frame, so we should see any write to it on the screen.

Then we convert the page to a raw pointer and write a value to offset 400. We don't write to the start of the page because the top line of the VGA buffer is directly shifted off the screen by the next println. We write the value 0x_f021_f077_f065_f04e, which represents the string "New!" on white background. As we learned in the “VGA Text Mode” post, writes to the VGA buffer should be volatile, so we use the write_volatile method.

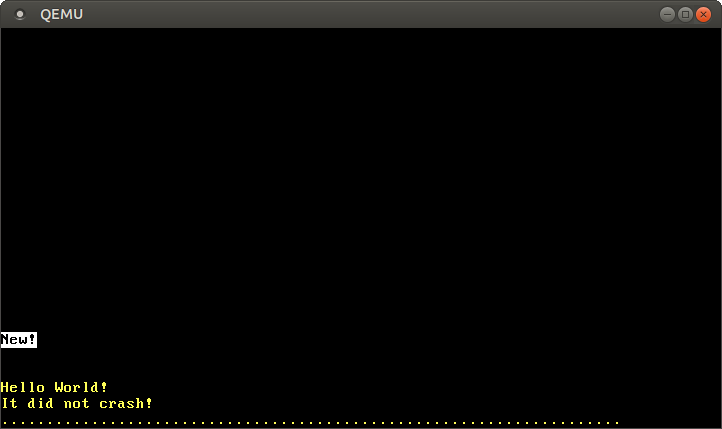

When we run it in QEMU, we see the following output:

The "New!" on the screen is by our write to page 0, which means that we successfully created a new mapping in the page tables.

Creating that mapping only worked because the level 1 table responsible for the page at address 0 already exists. When we try to map a page for that no level 1 table exists yet, the map_to function fails because it tries to allocate frames from the EmptyFrameAllocator for creating new page tables. We can see that happen when we try to map page 0xdeadbeaf000 instead of 0:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

[…]

let page = Page::containing_address(VirtAddr::new(0xdeadbeaf000));

[…]

}

When we run it, a panic with the following error message occurs:

panicked at 'map_to failed: FrameAllocationFailed', /…/result.rs:999:5

To map pages that don't have a level 1 page table yet we need to create a proper FrameAllocator. But how do we know which frames are unused and how much physical memory is available?

Allocating Frames

In order to create new page tables, we need to create a proper frame allocator. For that we use the memory_map that is passed by the bootloader as part of the BootInfo struct:

// in src/memory.rs

use bootloader::bootinfo::MemoryMap;

/// A FrameAllocator that returns usable frames from the bootloader's memory map.

pub struct BootInfoFrameAllocator {

memory_map: &'static MemoryMap,

next: usize,

}

impl BootInfoFrameAllocator {

/// Create a FrameAllocator from the passed memory map.

///

/// This function is unsafe because the caller must guarantee that the passed

/// memory map is valid. The main requirement is that all frames that are marked

/// as `USABLE` in it are really unused.

pub unsafe fn init(memory_map: &'static MemoryMap) -> Self {

BootInfoFrameAllocator {

memory_map,

next: 0,

}

}

}

The struct has two fields: A 'static reference to the memory map passed by the bootloader and a next field that keeps track of number of the next frame that the allocator should return.

As we explained in the Boot Information section, the memory map is provided by the BIOS/UEFI firmware. It can only be queried very early in the boot process, so the bootloader already calls the respective functions for us. The memory map consists of a list of MemoryRegion structs, which contain the start address, the length, and the type (e.g. unused, reserved, etc.) of each memory region.

The init function initializes a BootInfoFrameAllocator with a given memory map. The next field is initialized with 0 and will be increased for every frame allocation to avoid returning the same frame twice. Since we don't know if the usable frames of the memory map were already used somewhere else, our init function must be unsafe to require additional guarantees from the caller.

A usable_frames Method

Before we implement the FrameAllocator trait, we add an auxiliary method that converts the memory map into an iterator of usable frames:

// in src/memory.rs

use bootloader::bootinfo::MemoryRegionType;

impl BootInfoFrameAllocator {

/// Returns an iterator over the usable frames specified in the memory map.

fn usable_frames(&self) -> impl Iterator<Item = PhysFrame> {

// get usable regions from memory map

let regions = self.memory_map.iter();

let usable_regions = regions

.filter(|r| r.region_type == MemoryRegionType::Usable);

// map each region to its address range

let addr_ranges = usable_regions

.map(|r| r.range.start_addr()..r.range.end_addr());

// transform to an iterator of frame start addresses

let frame_addresses = addr_ranges.flat_map(|r| r.step_by(4096));

// create `PhysFrame` types from the start addresses

frame_addresses.map(|addr| PhysFrame::containing_address(PhysAddr::new(addr)))

}

}

This function uses iterator combinator methods to transform the initial MemoryMap into an iterator of usable physical frames:

- First, we call the

itermethod to convert the memory map to an iterator ofMemoryRegions. - Then we use the

filtermethod to skip any reserved or otherwise unavailable regions. The bootloader updates the memory map for all the mappings it creates, so frames that are used by our kernel (code, data or stack) or to store the boot information are already marked asInUseor similar. Thus we can be sure thatUsableframes are not used somewhere else. - Afterwards, we use the

mapcombinator and Rust's range syntax to transform our iterator of memory regions to an iterator of address ranges. - Next, we use

flat_mapto transform the address ranges into an iterator of frame start addresses, choosing every 4096th address usingstep_by. Since 4096 bytes (= 4 KiB) is the page size, we get the start address of each frame. The bootloader page aligns all usable memory areas so that we don't need any alignment or rounding code here. By usingflat_mapinstead ofmap, we get anIterator<Item = u64>instead of anIterator<Item = Iterator<Item = u64>>. - Finally, we convert the start addresses to

PhysFrametypes to construct the anIterator<Item = PhysFrame>.

The return type of the function uses the impl Trait feature. This way, we can specify that we return some type that implements the Iterator trait with item type PhysFrame, but don't need to name the concrete return type. This is important here because we can't name the concrete type since it depends on unnamable closure types.

Implementing the FrameAllocator Trait

Now we can implement the FrameAllocator trait:

// in src/memory.rs

unsafe impl FrameAllocator<Size4KiB> for BootInfoFrameAllocator {

fn allocate_frame(&mut self) -> Option<PhysFrame> {

let frame = self.usable_frames().nth(self.next);

self.next += 1;

frame

}

}

We first use the usable_frames method to get an iterator of usable frames from the memory map. Then, we use the Iterator::nth function to get the frame with index self.next (thereby skipping (self.next - 1) frames). Before returning that frame, we increase self.next by one so that we return the following frame on the next call.

This implementation is not quite optimal since it recreates the usable_frame allocator on every allocation. It would be better to directly store the iterator as a struct field instead. Then we wouldn't need the nth method and could just call next on every allocation. The problem with this approach is that it's not possible to store an impl Trait type in a struct field currently. It might work someday when named existential types are fully implemented.

Using the BootInfoFrameAllocator

We can now modify our kernel_main function to pass a BootInfoFrameAllocator instance instead of an EmptyFrameAllocator:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

use blog_os::memory::BootInfoFrameAllocator;

[…]

let mut frame_allocator = unsafe {

BootInfoFrameAllocator::init(&boot_info.memory_map)

};

[…]

}

With the boot info frame allocator, the mapping succeeds and we see the black-on-white "New!" on the screen again. Behind the scenes, the map_to method creates the missing page tables in the following way:

- Allocate an unused frame from the passed

frame_allocator. - Zero the frame to create a new, empty page table.

- Map the entry of the higher level table to that frame.

- Continue with the next table level.

While our create_example_mapping function is just some example code, we are now able to create new mappings for arbitrary pages. This will be essential for allocating memory or implementing multithreading in future posts.

At this point, we should delete the create_example_mapping function again to avoid accidentally invoking undefined behavior, as explained above.

Summary

In this post we learned about different techniques to access the physical frames of page tables, including identity mapping, mapping of the complete physical memory, temporary mapping, and recursive page tables. We chose to map the complete physical memory since it's simple, portable, and powerful.

We can't map the physical memory from our kernel without page table access, so we needed support from the bootloader. The bootloader crate supports creating the required mapping through optional cargo features. It passes the required information to our kernel in the form of a &BootInfo argument to our entry point function.

For our implementation, we first manually traversed the page tables to implement a translation function, and then used the MappedPageTable type of the x86_64 crate. We also learned how to create new mappings in the page table and how to create the necessary FrameAllocator on top of the memory map passed by the bootloader.

What's next?

The next post will create a heap memory region for our kernel, which will allow us to allocate memory and use various collection types.