This still won't compile on account of the fact that the `Point` type apparently doesn't implement `Into<(usize, usize)>`. Attempting to change the type just results in more issues

22 KiB

+++ title = "Screen Output" weight = 3 path = "screen-output" date = 0000-01-01 draft = true

[extra] chapter = "Basic I/O" icon = '''''' +++

In this post we focus on the framebuffer, a special memory region that controls the screen output. Using an external crate, we will create functions for writing individual pixels, lines, and various shapes. In the the second half of this post, we will explore text rendering and learn how to print the obligatory "Hello, World!".

This blog is openly developed on GitHub.

If you have any problems or questions, please open an issue there.

You can also leave comments at the bottom.

The complete source code for this post can be found in the post-3.3 branch.

Bitmap Images

In the previous post, we learned how to make our minimal kernel bootable.

Using the BootInfo provided by the bootloader, we were able to access a special memory region called the framebuffer, which controls the screen output.

We wrote some example code to display a gray background:

// in kernel/src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static mut BootInfo) -> ! {

if let Some(framebuffer) = boot_info.framebuffer.as_mut() {

for byte in framebuffer.buffer_mut() {

*byte = 0x90;

}

}

loop {}

}

The reason that the above code affects the screen output is because the graphics card interprets the framebuffer memory as a bitmap image. A bitmap describes an image through a predefined number of bytes per pixel. The pixels are laid out line by line, typically starting at the top.

For example, the pixels of an image with width 10 and height 3 would be typically stored in this order:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

So top left pixel is stored at offset 0 in the bitmap array.

The pixel on its right is at pixel offset 1.

The first pixel of the next line starts at pixel offset line_length, which is 10 in this case.

The last line starts at pixel offset 20, which is line_length * 2.

Padding

Depending on the hardware and GPU firmware, it is often more efficient to make lines start at well-aligned offsets. Because of this, there is often some additional padding at the end of each line. So the actual memory layout of the 10x3 example image might look like this, with the padding marked as yellow:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 |

So now the second line starts at pixel offset 12. The two pixels at the end of each line are considered as padding and ignored. So if we want to set the first pixel of the second line, we need to be aware of the additional padding and set the pixel at offset 12 instead of offset 10.

The line length plus the padding bytes is typically called the stride or pitch of the buffer. In the example above, the stride is 12 and the line length is 10.

Since the amount of padding depends on the hardware, the stride is only known at runtime.

The bootloader crate queries the framebuffer parameters from the UEFI or BIOS firmware and reports them as part of the BootInfo.

It provides the stride of the framebuffer, among other parameters, in form of a FrameBufferInfo struct that can be created using the FrameBuffer::info method.

Color formats

The FrameBufferInfo also specifies the PixelFormat of the framebuffer, which also depends on the underlying hardware.

Using this information, we can set pixels to different colors.

For example, the PixelFormat::Rgb variant specifies that each pixel is represented in the RGB color space, which stores the red, green, and blue parts of the pixel as separate bytes.

In this model, the color red would be represented as the three bytes [255, 0, 0], or 0xff0000 in hexadecimal representation.

The color yellow is represented the addition of red and green, which results in [255, 255, 0] (or 0xffff00 in hexadecimal representation).

While the Rgb format is most common, there are also framebuffers that use a different color format.

For example, the PixelFormat::Bgr stores the three colors in inverted order, i.e. blue first and red last.

There are also buffers that don't support colors at all and can represent only grayscale pixels.

The bootloader_api crate reports such buffers as PixelFormat::U8.

Note that there might be some additional padding at the pixel-level as well.

For example, an Rgb pixel might be stored as 4 bytes instead of 3 to ensure 32-bit alignment.

The number of bytes per pixel is reported by the bootloader in the FrameBufferInfo::bytes_per_pixel field.

Setting specific Pixels

Based on this above details, we can now create a function to set a specific pixel to a certain color.

We start by creating a new framebuffer module:

// in kernel/src/main.rs

// declare a submodule -> the compiler will automatically look

// for a file named `framebuffer.rs` or `framebuffer/mod.rs`

mod framebuffer;

In the new module, we create basic structs for representing pixel positions and colors:

// in new kernel/src/framebuffer.rs file

use bootloader_api::info::FrameBuffer;

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub struct Position {

pub x: usize,

pub y: usize,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

pub struct Color {

pub red: u8,

pub green: u8,

pub blue: u8,

}

By marking the sturcts and their fields as pub, we make them accessible from the parent kernel module.

We use the #[derive] attribute to implement the Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, and Eq traits of Rust's core library.

These traits allow us to duplicate, compare, and print the structs.

Next, we create a function for setting a specific pixel in the framebuffer to a given color:

// in new kernel/src/framebuffer.rs file

use bootloader_api::info::PixelFormat;

pub fn set_pixel_in(framebuffer: &mut FrameBuffer, position: Position, color: Color) {

let info = framebuffer.info();

// calculate offset to first byte of pixel

let byte_offset = {

// use stride to calculate pixel offset of target line

let line_offset = position.y * info.stride;

// add x position to get the absolute pixel offset in buffer

let pixel_offset = line_offset + position.x;

// convert to byte offset

pixel_offset * info.bytes_per_pixel

};

// set pixel based on color format

let pixel_buffer = &mut framebuffer.buffer_mut()[byte_offset..];

match info.pixel_format {

PixelFormat::Rgb => {

pixel_buffer[0] = color.red;

pixel_buffer[1] = color.green;

pixel_buffer[2] = color.blue;

}

PixelFormat::Bgr => {

pixel_buffer[0] = color.blue;

pixel_buffer[1] = color.green;

pixel_buffer[2] = color.red;

}

PixelFormat::U8 => {

// use a simple average-based grayscale transform

let gray = color.red / 3 + color.green / 3 + color.blue / 3;

pixel_buffer[0] = gray;

}

other => panic!("unknown pixel format {other:?}"),

}

}

The first step is to calculate the byte offset within the framebuffer slice at which the pixel starts.

For this, we first calculate the pixel offset of the line by multiplying the y position with the stride of the framebuffer, i.e. its line width plus the line padding.

We then add the x position to get the absolute index of the pixel.

As the framebuffer slice is a byte slice, we need to transform the pixel index to a byte offset by multiplying it with the number of bytes_per_pixel.

The second step is to set the pixel to the desired color.

We first use the FrameBuffer::buffer_mut method to get access to the actual bytes of the framebuffer in form of a slice.

Then, we use the slicing operator [byte_offset..] to get a sub-slice starting at the byte_offset of the target pixel.

As the write operation depends on the pixel format, we use a match statement:

- For

Rgbframebuffers, we write three bytes; first red, then green, then blue. - For

Bgrframebuffers, we also write three bytes, but blue first and red last. - For

U8framebuffers, we first convert the color to grayscale by taking the average of the three color channels. Note that there are multiple different ways to convert colors to grayscale, so you can also use different factors here. - For all other framebuffer formats, we panic for now.

Let's try to use our new function to write a blue pixel in our kernel_main function:

// in kernel/src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static mut BootInfo) -> ! {

if let Some(framebuffer) = boot_info.framebuffer.as_mut() {

let position = framebuffer::Position { x: 20, y: 100 };

let color = framebuffer::Color {

red: 0,

green: 0,

blue: 255,

};

framebuffer::set_pixel_in(framebuffer, position, color);

}

loop {}

}

When we run our code in QEMU using cargo run --bin qemu-bios (or --bin qemu-uefi) and look very closely, we can see the blue pixel.

It's really difficult to see, so I marked with an arrow below:

As this single pixel is too difficult to see, let's draw a filled square of 100x100 pixels instead:

// in kernel/src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static mut BootInfo) -> ! {

if let Some(framebuffer) = boot_info.framebuffer.as_mut() {

let color = framebuffer::Color {

red: 0,

green: 0,

blue: 255,

};

for x in 0..100 {

for y in 0..100 {

let position = framebuffer::Position {

x: 20 + x,

y: 100 + y,

};

framebuffer::set_pixel_in(framebuffer, position, color);

}

}

}

loop {}

}

Now we clearly see that our code works as intended:

Feel free to experiment with different positions and colors if you like. You can also try to draw a circle instead of a square, or a line with a certain thickness.

As you can probably imagine, it would be a lot of work to draw more complex shapes this way.

One example for such complex shapes is text, i.e. the rendering of letters and punctuation.

Fortunately, there is the nice no_std-compatible embedded-graphics crate, which provides draw functions for text, various shapes, and image data.

The embedded-graphics crate

Implementing DrawTarget

// in kernel/src/framebuffer.rs

use embedded_graphics::pixelcolor::Rgb888;

pub struct Display {

framebuffer: FrameBuffer,

}

impl Display {

pub fn new(framebuffer: FrameBuffer) -> Display {

Self { framebuffer }

}

fn draw_pixel(&mut self, Pixel(coordinates, color): Pixel<Rgb888>) {

// ignore any pixels that are out of bounds.

let (width, height) = {

let info = self.framebuffer.info();

(info.width, info.height)

}

if let Ok((x @ 0..width, y @ 0..height)) = coordinates.try_into() {

let color = Color { red: color.r(), green: color.g(), blue: color.b()};

set_pixel_in(&mut self.framebuffer, Position { x, y }, color);

}

}

}

impl embedded_graphics::draw_target::DrawTarget for Display {

type Color = Rgb888;

/// Drawing operations can never fail.

type Error = core::convert::Infallible;

fn draw_iter<I>(&mut self, pixels: I) -> Result<(), Self::Error>

where

I: IntoIterator<Item = Pixel<Self::Color>>,

{

for pixel in pixels.into_iter() {

self.draw_pixel(pixel);

}

Ok(())

}

}

draw shapes and pixels directly onto the framebuffer. That's fine and all, but how is one able to go from that to displaying text on the screen? Understanding this requires taking a deep dive into how characters are rendered behind the scenes.

When a key is pressed on the keyboard, it sends a character code to the CPU. It's the CPU's job at that point to then interpret the character code and match it with an image to draw on the screen. The image is then sent to either the GPU or the framebuffer (the latter in our case) to be drawn on the screen, and the user sees that image as a letter, number, CJK character, emoji, or whatever else he or she wanted to have displayed by pressing that key.

In most other programming languages, implementing this behind the scenes can be a daunting task. With Rust, however, we have a toolset at our disposal that can pave the way for setting up proper framebuffer logging using very little code of our own.

The log crate

Rust developers used to writing user-mode code will recognize the log crate from a mile away:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

log = { version = "0.4.17", default-features = false }

This crate has both a set of macros for logging either to the console or to a log file for later reading and a trait — also called Log with a capital L — that can be implemented to provide a backend, called a Logger in Rust parlance. Loggers are provided by a myriad of crates for a wide variety of use cases, and some of them even run on bare metal. We already used one such extant logger in the UEFI booting module when we used the logger provided by the uefi crate to print text to the UEFI console. That won't work in the kernel, however, because UEFI boot services need to be active in order for the UEFI logger to be usable.

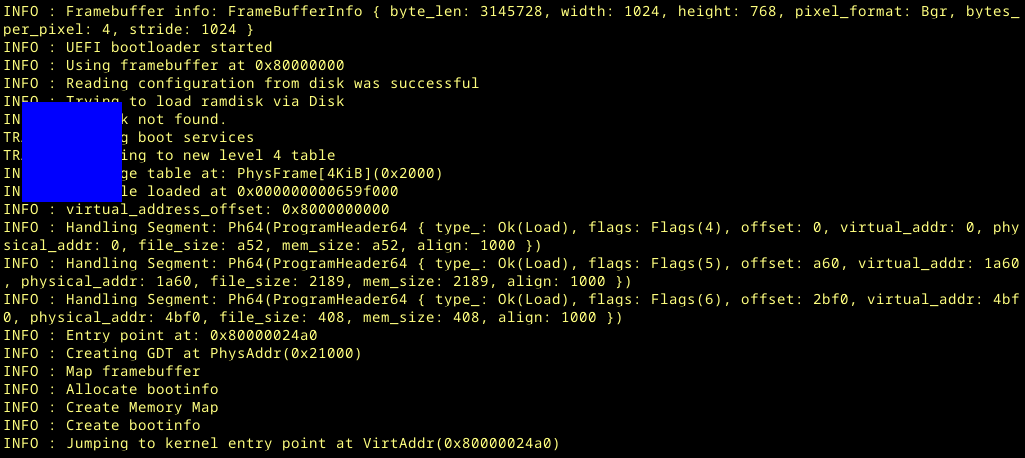

If you were paying attention to the post before that one, however, you may have noticed that the bootloader is itself able to log directly to the framebuffer as it did when we booted the barebones kernel for the first time, and unlike the UEFI console logger, this logger is usable long after UEFI boot services are exited. It's this logger, therefore, that provides the easiest means of implementation on our end.

bootloader-x86_64-common

In version 0.11.x of the bootloader crate, each component is separate, unlike in 0.10.x where the bootloader was a huge monolith. This is fantastic as it means that a lot of the APIs that the bootloader uses behind the scenes are also free for kernels to use, including, of course, the logger. The set of APIs that the logger belongs to are in a crate called bootloader-x86_64-common which also contains some other useful abstractions related to things like memory management that will come in handy later:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

bootloader-x86_64-common = "0.11.3"

For now, however, only the logger will be used. If you are curious as to how this logger is written behind the scenes, however, don't worry; a sub-module of this chapter will include a tutorial on how to write a custom logger from scratch.

Putting it all together

Before we use the bootloader's logger, we first need to initialize it. This requires creating a static instance, since it needs to live for as long as the kernel lives — which would mean for as long as the computer is powered on. Unfortunately, this is easier said than done, as Rust statics can be rather finicky — understandably so for security reasons. Luckily, there's a crate for this too.

The conquer_once crate

Those used to using the standard library know that it provides a OnceCell which is exactly what it sounds like: you write to it only once, and then after that it's just there to use whenever. We're in a kernel and don't have access to the standard library, however, so is there a crate on crates.io that provides a replacement? Ah, yes there is:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

conquer-once = { version = "0.4.0", default-features = false }

Note that we need to add default-features = false to our conquer-once dependency —that's because the conquer-once crate tries to pull in the standard library by default, which in the kernel will result in compilation errors.

Now that we've added our two dependencies, it's time to use them:

// in src/main.rs

use conquer_once::spin::OnceCell;

use bootloader_x86_64_common::logger::LockedLogger;

// ...

pub(crate) static LOGGER: OnceCell<LockedLogger> = OnceCell::uninit();

By setting the logger up as a static OnceCell it becomes much easier to initialize. We use pub(crate) to ensure that the kernel can see it but nothing else can.

After this, it's time to actually initialize it. To do that, we use a function:

// in src/main.rs

use bootloader_api::info::FrameBufferInfo;

// ...

pub(crate) fn init_logger(buffer: &'static mut [u8], info: FrameBufferInfo) {

let logger = LOGGER.get_or_init(move || LockedLogger::new(buffer, info, true, false));

log::set_logger(logger).expect("Logger already set");

log::set_max_level(log::LevelFilter::Trace);

log::info!("Hello, Kernel Mode!");

}

This function takes two parameters: a byte slice representing a raw framebuffer and a FrameBufferInfo structure containing information about the first parameter. Getting those parameters, however, requires jumping through some hoops to satisfy the borrow checker:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static mut bootloader_api::BootInfo) -> ! {

// ...

// free the doubly wrapped framebuffer from the boot info struct

let frame_buffer_optional = &mut boot_info.framebuffer;

// free the wrapped framebuffer from the FFI-safe abstraction provided by bootloader_api

let frame_buffer_option = frame_buffer_optional.as_mut();

// unwrap the framebuffer

let frame_buffer_struct = frame_buffer_option.unwrap();

// extract the framebuffer info and, to satisfy the borrow checker, clone it

let frame_buffer_info = frame_buffer.info().clone();

// get the framebuffer's mutable raw byte slice

let raw_frame_buffer = frame_buffer_struct.buffer_mut();

// finally, initialize the logger using the last two variables

init_logger(raw_frame_buffer, frame_buffer_info);

// ...

}

Any one of these steps, if skipped, will cause the borrow checker to throw a hissy fit due to the use of the move || closure by the initializer function. With this, however, you're done, and you'll know the logger has been initialized when you see "Hello, Kernel Mode!" printed on the screen.