39 KiB

+++ title = "Allocator Designs" weight = 11 path = "allocator-designs" date = 0000-01-01 +++

This post explains how to implement heap allocators from scratch. It presents different allocator designs and explains their advantages and drawbacks. We then use this knowledge to create a kernel allocator with improved performance.

TODO

This blog is openly developed on GitHub. If you have any problems or questions, please open an issue there. You can also leave comments at the bottom. The complete source code for this post can be found in the post-11 branch.

TODO optional

Introduction

In the previous post we added basic support for heap allocations to our kernel. For that, we created a new memory region in the page tables and used the linked_list_allocator crate to manage that memory. While we have a working heap now, we left most of the work to the allocator crate without understanding how it works.

In this post, we will show how to create our own heap allocator from scratch instead of relying on an existing allocator crate. We will discuss different allocator designs, including a simplistic bump allocator and a basic fixed-size block allocator, and use this knowledge to implement an allocator with improved performance.

Design Goals

The responsibility of an allocator is to manage the available heap memory. It needs to return unused memory on alloc calls and keep track of memory freed by dealloc so that it can be reused again. Most importantly, it must never hand out memory that is already in use somewhere else because this would cause undefined behavior.

Apart from correctness, there are many secondary design goals. For example, it should effectively utilize the available memory and keep fragmentation low. Furthermore, it should work well for concurrent applications and scale to any number of processors. For maximal performance, it could even optimize the memory layout with respect to the CPU caches to improve cache locality and avoid false sharing.

These requirements can make good allocators very complex. For example, jemalloc has over 30.000 lines of code. This complexity often undesired in kernel code where a single bug can lead to severe security vulnerabilities. Fortunately, the allocation patterns of kernel code are often much simpler compared to userspace code, so that relatively simple allocator designs often suffice.

In the following we present three possible kernel allocator designs and explain their advantages and drawbacks.

Bump Allocator

The most simple allocator design is a bump allocator. It allocates memory linearly and only keeps track of the number of allocated bytes and the number of allocations. It is only useful in very specific use cases because it has a severe limitation: it can only free all memory at once.

The base type looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub struct BumpAllocator {

heap_start: usize,

heap_end: usize,

next: usize,

allocations: usize,

}

impl BumpAllocator {

/// Creates a new bump allocator with the given heap bounds.

///

/// This method is unsafe because the caller must ensure that the given

/// memory range is unused.

pub const unsafe fn new(heap_start: usize, heap_size: usize) -> Self {

BumpAllocator {

heap_start,

heap_end: heap_start + heap_size,

next: heap_start,

allocations: 0,

}

}

}

Instead of using the HEAP_START and HEAP_SIZE constants directly, we use separate heap_start and heap_end fields. This makes the type more flexible, for example it also works when we only want to assign a part of the heap region. The purpose of the next field is to always point to the first unused byte of the heap, i.e. the start address of the next allocation. The allocations field is a simple counter for the active allocations with the goal of resetting the allocator after the last allocation was freed.

We provide a simple constructor function that creates a new BumpAllocator. It initializes the heap_start and heap_end fields using the given start address and size. The allocations counter is initialized with 0. The next field is set to heap_start since the whole heap should be unused at this point. Since this is something that the caller must guarantee, the function needs to be unsafe. Given an invalid memory range, the planned implementation of the GlobalAlloc trait would cause undefined behavior when it is used as global allocator.

A Locked Wrapper

Implementing the [GlobalAlloc] trait directly for the BumpAllocator struct is not possible. The problem is that the alloc and dealloc methods of the trait only take an immutable &self reference, but we need to update the next and allocations fields for every allocation, which is only possible with an exclusive &mut self reference. The reason that the GlobalAlloc trait is specified this way is that the global allocator needs to be stored in an immutable static that only allows &self references.

To be able to implement the trait for our BumpAllocator struct, we need to add synchronized interior mutability to get mutable field access through the &self reference. A type that adds the required synchronization and allows interior mutabilty is the spin::Mutex spinlock that we already used multiple times for our kernel, for example for our VGA buffer writer. To use it, we create a Locked wrapper type:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub struct Locked<A> {

inner: spin::Mutex<A>,

}

impl<A> Locked<A> {

pub const fn new(inner: A) -> Self {

Locked {

inner: spin::Mutex::new(inner),

}

}

}

The type is a generic wrapper around a spin::Mutex<A>. It imposes no restrictions on the wrapped type A, so it can be used to wrap all kinds of types, not just allocators. It provides a simple new constructor function that wraps a given value.

Implementing GlobalAlloc

With the help of the Locked wrapper type we now can implement the GlobalAlloc trait for our bump allocator. The trick is to implement the trait not for the BumpAllocator directly, but for the wrapped Locked<BumpAllocator> type. The implementation looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

unsafe impl GlobalAlloc for Locked<BumpAllocator> {

unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8 {

let mut bump = self.inner.lock();

let alloc_start = align_up(bump.next, layout.align());

let alloc_end = alloc_start + layout.size();

if alloc_end > bump.heap_end {

null_mut() // out of memory

} else {

bump.next = alloc_end;

bump.allocations += 1;

alloc_start as *mut u8

}

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, _ptr: *mut u8, _layout: Layout) {

let mut bump = self.inner.lock();

bump.allocations -= 1;

if bump.allocations == 0 {

bump.next = bump.heap_start;

}

}

}

The first step for both alloc and dealloc is to call the Mutex::lock method to get a mutable reference to the wrapped allocator type. The instance remains locked until the end of the method, so that no data race can occur in multithreaded contexts (we will add threading support soon).

The alloc implementation first performs the required alignment on the next address, as specified by the given [Layout]. This yields the start address of the allocation. The code for the align_up function is shown below. Next, we add the requested allocation size to alloc_start to get the end address of the allocation. If it is larger than the end address of the heap, we return a null pointer since there is not enough memory available. Otherwise, we update the next address (the next allocation should start after the current allocation), increase the allocations counter by 1, and return the alloc_start address converted to a *mut u8 pointer.

The dealloc function ignores the given pointer and Layout arguments. Instead, it just decreases the allocations counter. If the counter reaches 0 again, it means that all allocations were freed again. In this case, it resets the next address to the heap_start address to make the complete heap memory available again.

The last remaining part of the implementation is the align_up function, which looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

fn align_up(addr: usize, align: usize) -> usize {

let remainder = addr % align;

if remainder == 0 {

addr // addr already aligned

} else {

addr - remainder + align

}

}

The function first computes the remainder of the division of addr by align. If the remainder is 0, the address is already aligned with the given alignment. Otherwise, we align the address by subtracting the remainder (so that the new remainder is 0) and then adding the alignment (so that the address does not become smaller than the original address).

Using It

To use the bump allocator instead of the dummy allocator, we need to update the ALLOCATOR static in lib.rs:

// in src/lib.rs

use allocator::{Locked, BumpAllocator, HEAP_START, HEAP_SIZE};

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOCATOR: Locked<BumpAllocator> =

Locked::new(BumpAllocator::new(HEAP_START, HEAP_SIZE));

Here it becomes important that we declared both the Locked::new and the BumpAllocator::new as const functions. If they were normal functions, a compilation error would occur because the initialization expression of a static must evaluable at compile time.

Now we can use Box and Vec without runtime errors:

// in src/main.rs

use alloc::{boxed::Box, vec::Vec, collections::BTreeMap};

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// […] initialize interrupts, mapper, frame_allocator, heap

// allocate a number on the heap

let heap_value = Box::new(41);

println!("heap_value at {:p}", heap_value);

// create a dynamically sized vector

let mut vec = Vec::new();

for i in 0..500 {

vec.push(i);

}

println!("vec at {:p}", vec.as_slice());

// try to create one million boxes

for _ in 0..1_000_000 {

let _ = Box::new(1);

}

// […] call `test_main` in test context

println!("It did not crash!");

blog_os::hlt_loop();

}

This code example only uses the Box and Vec types, but there are many more allocation and collection types in the alloc crate that we can now all use in our kernel, including:

- the reference counted pointers

RcandArc - the owned string type

Stringand theformat!macro LinkedList- the growable ring buffer

VecDeque BinaryHeapBTreeMapandBTreeSet

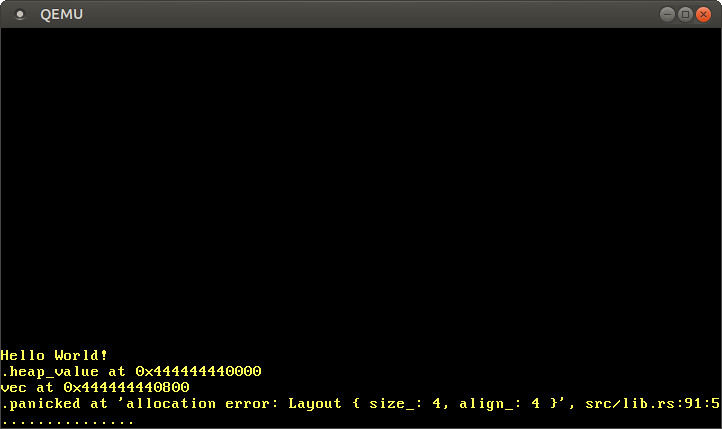

When we run our project now, we see the following:

As expected, we see that the Box and Vec values live on the heap, as indicated by the pointer starting with 0x_4444_4444. The reason that the vector starts at offset 0x800 is not that the boxed value is 0x800 bytes large, but the reallocations that occur when the vector needs to increase its capacity. For example, when the vector's capacity is 32 and we try to add the next element, the vector allocates a new backing array with capacity 64 behind the scenes and copies all elements over. Then it frees the old allocation, which in our case is equivalent to leaking it since our bump allocator doesn't reuse freed memory.

While the basic Box and Vec examples work as expected, our loop that tries to create one million boxes causes a panic. The reason is that the bump allocator never reuses freed memory, so that for each created Box a few bytes are leaked. This makes the bump allocator unsuitable for many applications in practice, apart from some very specific use cases.

When to use a Bump Allocator

The big advantage of bump allocation is that it's very fast. Compared to other allocator designs (see below) that need to actively look for a fitting memory block and perform various bookkeeping tasks on alloc and dealloc, a bump allocator can be optimized to just a few assembly instructions. This makes bump allocators useful for optimizing the allocation performance, for example when creating a virtual DOM library.

While a bump allocator is seldom used as the global allocator, the principle of bump allocation is often applied in form of arena allocation, which basically batches individual allocations together to improve performance. An example for an arena allocator for Rust is the toolshed crate.

Reusing Freed Memory?

The main limitation of a bump allocator is that it never reuses deallocated memory. The question is: Can we extend our bump allocator somehow to remove this limitation?

As we learned at the beginning of this post, allocations can live arbitarily long and can be freed in an arbitrary order. This means that we need to keep track of a potentially unbounded number of non-continuous, unused memory regions, as illustrated by the following example:

The graphic shows the heap over the course of time. At the beginning, the complete heap is unused and the next address is equal to heap_start (line 1). Then the first allocation occurs (line 2). In line 3, a second memory block is allocated and the first allocation is freed. Many more allocations are added in line 4. Half of them are very short-lived and already get freed in line 5, where also another new allocation is added.

Line 5 shows the fundamental problem: We have five unused memory regions with different sizes in total, but the next pointer can only point to the beginning of the last region. While we could store the start addresses and sizes of the other unused memory regions in an array of size 4 for this example, this isn't a general solution since we could easily create an example with 8, 16, or 1000 unused memory regions.

Normally when we have a potentially unbounded number of items, we can just use a heap allocated collection. This isn't really possible in our case, since the heap allocator can't depend on itself (it would cause endless recursion or deadlocks). So we need to find a different solution.

LinkedList Allocator

A common trick to keep track of an arbitrary number of free memory areas is to use these areas itself as backing storage. This utilizes the fact that the regions are still mapped to a virtual address and backed by a physical frame, but the stored information is not needed anymore. By storing the information about the freed region in the region itself, we can keep track of an unbounded number of freed regions without needing additional memory.

The most common implementation approach is to construct a single linked list in the freed memory, with each node being a freed memory region:

Each list node contains two fields: The size of the memory region and a pointer to the next unused memory region. With this approach, we only need a pointer to the first unused region (called head), independent of the number of memory regions.

In the following, we will create a simple LinkedListAllocator type that uses the above approach for keeping track of freed memory regions. Since the implementation is a bit longer, we will start with a simple placeholder type before we start to implement the alloc and dealloc operations.

The Allocator Type

We start by creating a private ListNode struct:

// in src/allocator.rs

struct ListNode {

size: usize,

next: Option<&'static mut ListNode>,

}

impl ListNode {

const fn new(size: usize) -> Self {

ListNode {

size,

next: None,

}

}

fn start_addr(&self) -> usize {

self as *const Self as usize

}

fn end_addr(&self) -> usize {

self.start_addr() + self.size

}

}

Like in the graphic, a list node has a size field and an optional pointer to the next node. The type has a simple constructor function and methods to calculate the start and end addresses of the represented region.

With the ListNode struct as building block, we can now create the LinkedListAllocator struct:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub struct LinkedListAllocator {

head: ListNode,

}

impl LinkedListAllocator {

pub const fn new() -> Self {

Self {

head: ListNode::new(0),

}

}

/// Initialize the allocator with the given heap bounds.

///

/// This function is unsafe because the caller must guarantee that the given

/// heap bounds are valid and that the heap is unused. This method must be

/// called only once.

pub unsafe fn init(&mut self, heap_start: usize, heap_size: usize) {

self.add_free_region(heap_start, heap_size);

}

/// Adds the given memory region to the front of the list.

unsafe fn add_free_region(&mut self, addr: usize, size: usize) {

unimplemented!();

}

}

The struct contains a head node that points to the first heap region. We are only interested in the value of the next pointer, so we set the size to 0 in the new function. Making head a ListNode instead of just a &'static mut ListNode has the advantage that the implementation of the alloc method will be simpler.

In contrast to the bump allocator, the new function doesn't initialize the allocator with the heap bounds. The reason is that the initialization requires to write a node to the heap memory, which can only happen at runtime. The new function, however, needs to be a const function that can be evaluated at compile time, because it will be used for initializing the ALLOCATOR static. To work around this, we provide a separate init method that can be called at runtime.

The init method uses a add_free_region method, whose implementation will be shown in a moment. For now, we use the unimplemented! macro to provide a placeholder implementation that always panics.

Our first goal is to set a prototype of the LinkedListAllocator as the global allocator. In order to be able to do that, we need to provide a placeholder implementation of the GlobalAlloc trait:

// in src/allocator.rs

unsafe impl GlobalAlloc for Locked<LinkedListAllocator> {

unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8 {

unimplemented!();

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout) {

unimplemented!();

}

}

Like with the bump allocator, we don't implement the trait directly for the LinkedListAllocator, but only for a wrapped Locked<LinkedListAllocator>. The Locked wrapper adds interior mutability through a spinlock, which allows us to modify the allocator instance even though the alloc and dealloc methods only take &self references. Instead of providing an implementation, we use the unimplemented! macro again to get a minimal prototype.

With this placeholder implementation, we can now change the global allocator to a LinkedListAllocator:

// in src/lib.rs

use allocator::{Locked, LinkedListAllocator};

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOCATOR: Locked<LinkedListAllocator> =

Locked::new(LinkedListAllocator::new());

Since the new method creates an empty allocator, we also need to update our allocator::init function to call LinkedListAllocator::init with the heap bounds:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub fn init_heap(

mapper: &mut impl Mapper<Size4KiB>,

frame_allocator: &mut impl FrameAllocator<Size4KiB>,

) -> Result<(), MapToError> {

// […] map all heap pages

// new

unsafe {

super::ALLOCATOR.inner.lock().init(HEAP_START, HEAP_SIZE);

}

Ok(())

}

It's important to call the init function after the mapping of the heap pages, because the function will already write to the heap (once we'll properly implement it). The unsafe block is safe here because we just mapped the heap region to unused frames, so that the passed heap region is valid.

When we run our code now, it will of course panic since it runs into the unimplemented! in add_free_region. Let's fix that by providing a proper implementation for that method.

The add_free_region Method

The add_free_region method provides the fundamental push operation on the linked list. We currently only call this method from init, but it will also be the central method in our dealloc implementation. Remember, the dealloc method is called when an allocated memory region is freed again. To keep track of this freed memory region, we want to push it to the linked list.

The implementation of the add_free_region method looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

impl LinkedListAllocator {

/// Adds the given memory region to the front of the list.

unsafe fn add_free_region(&mut self, addr: usize, size: usize) {

// ensure that the freed region is capable of holding ListNode

assert!(align_up(addr, mem::align_of::<ListNode>()) == addr);

assert!(size >= mem::size_of::<ListNode>());

// create a new list node and append it at the start of the list

let mut node = ListNode::new(size);

node.next = self.head.next.take();

let node_ptr = addr as *mut ListNode;

node_ptr.write(node);

self.head.next = Some(&mut *node_ptr)

}

}

The method takes a memory region represented by an address and size as argument and adds it to the front of the list. First, it ensures that the given region has the neccessary size and alignment for storing a ListNode. Then it creates the node and inserts it to the list through the following steps:

Step 0 shows the state of the heap before add_free_region is called. In step 1, the method is called with the memory region marked as freed in the graphic. After the initial checks, the method creates a new node on its stack with the size of the freed region. It then uses the Option::take method to set the next pointer of the node to the current head pointer, thereby resetting the head pointer to None.

In step 2, the method writes the newly created node to the beginning of the freed memory region through the write method. It then points the head pointer to the new node. The resulting pointer structure looks a bit chaotic because the freed region is always inserted at the beginning of the list, but if we follow the pointers we see that each free region is still reachable from the head pointer.

The find_region Method

The second fundamental operation on a linked list is finding an entry and removing it from the list. This is the central operation needed for implementing the alloc method. We implement the operation as a find_region method in the following way:

// in src/allocator.rs

impl LinkedListAllocator {

/// Looks for a free region with the given size and alignment and removes

/// it from the list.

///

/// Returns a tuple of the list node and the start address of the allocation.

fn find_region(&mut self, size: usize, align: usize)

-> Option<(&'static mut ListNode, usize)>

{

// reference to current list node, updated for each iteration

let mut current = &mut self.head;

// look for a large enough memory region in linked list

while let Some(ref mut region) = current.next {

if let Ok(alloc_start) = Self::alloc_from_region(®ion, size, align) {

// region suitable for allocation -> remove node from list

let next = region.next.take();

let ret = Some((current.next.take().unwrap(), alloc_start));

current.next = next;

return ret;

} else {

// region not suitable -> continue with next region

current = current.next.as_mut().unwrap();

}

}

// no suitable region found

None

}

}

The method uses a current variable and a while let loop to iterate over the list elements. At the beginning, current is set to the (dummy) head node. On each iteration, it is then updated to to the next field of the current node (in the else block). If the region is suitable for an allocation with the given size and alignment, the region is removed from the list and returned together with the alloc_start address.

When the current.next pointer becomes None, the loop exits. This means that we iterated over the whole list but found no region that is suitable for an allocation. In that case, we return None. The check whether a region is suitable is done by a alloc_from_region function, whose implementation will be shown in a moment.

Let's take a more detailed look at how a suitable region is removed from the list:

Step 0 shows the situation before any pointer adjustments. The region and current regions and the region.next and current.next pointers are marked in the graphic. In step 1, both the region.next and current.next pointers are reset to None by using the Option::take method. The original pointers are stored in local variables called next and ret.

In step 2, the current.next pointer is set to the local next pointer, which is the original region.next pointer. The effect is that current now directly points to the region after region, so that region is no longer element of the linked list. The function then returns the pointer to region stored in the local ret variable.

The alloc_from_region Function

The alloc_from_region function returns whether a region is suitable for an allocation with given size and alignment. It is defined like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

impl LinkedListAllocator {

/// Try to use the given region for an allocation with given size and alignment.

///

/// Returns the allocation start address on success.

fn alloc_from_region(region: &ListNode, size: usize, align: usize)

-> Result<usize, ()>

{

let alloc_start = align_up(region.start_addr(), align);

let alloc_end = alloc_start + size;

if alloc_end > region.end_addr() {

// region too small

return Err(());

}

let excess_size = region.end_addr() - alloc_end;

if excess_size > 0 && excess_size < mem::size_of::<ListNode>() {

// rest of region too small to hold a ListNode (required because the

// allocation splits the region in a used and a free part)

return Err(());

}

// region suitable for allocation

Ok(alloc_start)

}

}

First, the function calculates the start and end address of a potential allocation, using the align_up function we defined earlier. If the end address is behind the end address of the region, the allocation doesn't fit in the region and we return an error.

The function performs a less obvious check after that. This check is neccessary because most of the time an allocation does not fit a suitable region perfectly, so that a part of the region remains usable after the allocation. This part of the region must store its own ListNode after the allocation, so it must be large enough to do so. The check verifies exactly that: either the allocation fits perfectly (excess_size == 0) or the excess size is large enough to store a ListNode.

Implementing GlobalAlloc

With the fundamental operations provided by the add_free_region and find_region methods, we can now finally implement the GlobalAlloc trait:

// in src/allocator.rs

unsafe impl GlobalAlloc for Locked<LinkedListAllocator> {

unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8 {

// perform layout adjustments

let (size, align) = LinkedListAllocator::size_align(layout);

let mut allocator = self.inner.lock();

if let Some((region, alloc_start)) = allocator.find_region(size, align) {

let alloc_end = alloc_start + size;

let excess_size = region.end_addr() - alloc_end;

if excess_size > 0 {

allocator.add_free_region(alloc_end, excess_size);

}

alloc_start as *mut u8

} else {

null_mut()

}

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout) {

// perform layout adjustments

let (size, _) = LinkedListAllocator::size_align(layout);

self.inner.lock().add_free_region(ptr as usize, size)

}

}

Let's start with the dealloc method because it is simpler: First, it performs some layout adjustments, which we will explain in a moment, and retrieves a &mut LinkedListAllocator reference by calling the Mutex::lock function on the Locked wrapper. Then it calls the add_free_region function to add the deallocated region to the free list.

The alloc method is a bit more complex. It starts with the same layout adjustments and also calls the Mutex::lock function to receive a mutable allocator reference. Then it uses the find_region method to find a suitable memory region for the allocation and remove it from the list. If this doesn't succeed and None is returned, it returns null_mut to signal an error as there is no suitable memory region.

In the success case, the find_region method returns a tuple of the suitable region (no longer in the list) and the start address of the allocation. Using alloc_start, the allocation size, and the end address of the region, it calculates the end address of the allocation and the excess size again. If the excess size is not null, it calls add_free_region to add the excess size of the memory region back to the free list. Finally, it returns the alloc_start address casted as a *mut u8 pointer.

Layout Adjustments

// in src/allocator.rs

impl LinkedListAllocator {

/// Adjust the given layout so that the resulting allocated memory

/// region is also capable of storing a `ListNode`.

///

/// Returns the adjusted size and alignment as a (size, align) tuple.

fn size_align(layout: Layout) -> (usize, usize) {

let layout = layout.align_to(mem::align_of::<ListNode>())

.and_then(|l| l.pad_to_align())

.expect("adjusting alignment failed");

let size = layout.size().max(mem::size_of::<ListNode>());

(size, layout.align())

}

}

Allocation

In order to allocate a block of memory, we need to find a hole that satisfies the size and alignment requirements. If the found hole is larger than required, we split it into two smaller holes. For example, when we allocate a 24 byte block right after initialization, we split the single hole into a hole of size 24 and a hole with the remaining size:

Then we use the new 24 byte hole to perform the allocation:

To find a suitable hole, we can use several search strategies:

- best fit: Search the whole list and choose the smallest hole that satisfies the requirements.

- worst fit: Search the whole list and choose the largest hole that satisfies the requirements.

- first fit: Search the list from the beginning and choose the first hole that satisfies the requirements.

Each strategy has its advantages and disadvantages. Best fit uses the smallest hole possible and leaves larger holes for large allocations. But splitting the smallest hole might create a tiny hole, which is too small for most allocations. In contrast, the worst fit strategy always chooses the largest hole. Thus, it does not create tiny holes, but it consumes the large block, which might be required for large allocations.

For our use case, the best fit strategy is better than worst fit. The reason is that we have a minimal hole size of 16 bytes, since each hole needs to be able to store a size (8 bytes) and a pointer to the next hole (8 bytes). Thus, even the best fit strategy leads to holes of usable size. Furthermore, we will need to allocate very large blocks occasionally (e.g. for DMA buffers).

However, both best fit and worst fit have a significant problem: They need to scan the whole list for each allocation in order to find the optimal block. This leads to long allocation times if the list is long. The first fit strategy does not have this problem, as it returns as soon as it finds a suitable hole. It is fairly fast for small allocations and might only need to scan the whole list for large allocations.

Deallocation

To deallocate a block of memory, we can just insert its corresponding hole somewhere into the list. However, we need to merge adjacent holes. Otherwise, we are unable to reuse the freed memory for larger allocations. For example:

In order to use these adjacent holes for a large allocation, we need to merge them to a single large hole first:

The easiest way to ensure that adjacent holes are always merged, is to keep the hole list sorted by address. Thus, we only need to check the predecessor and the successor in the list when we free a memory block. If they are adjacent to the freed block, we merge the corresponding holes. Else, we insert the freed block as a new hole at the correct position.

Implementation

The detailed implementation would go beyond the scope of this post, since it contains several hidden difficulties. For example:

- Several merge cases: Merge with the previous hole, merge with the next hole, merge with both holes.

- We need to satisfy the alignment requirements, which requires additional splitting logic.

- The minimal hole size of 16 bytes: We must not create smaller holes when splitting a hole.

I created the linked_list_allocator crate to handle all of these cases. It consists of a Heap struct that provides an allocate_first_fit and a deallocate method. It also contains a LockedHeap type that wraps Heap into spinlock so that it's usable as a static system allocator. If you are interested in the implementation details, check out the source code.

We need to add the extern crate to our Cargo.toml and our lib.rs:

> cargo add linked_list_allocator

// in src/lib.rs

extern crate linked_list_allocator;

Now we can change our global allocator:

use linked_list_allocator::LockedHeap;

#[global_allocator]

static HEAP_ALLOCATOR: LockedHeap = LockedHeap::empty();

We can't initialize the linked list allocator statically, since it needs to initialize the first hole (like described above). This can't be done at compile time, so the function can't be a const function. Therefore we can only create an empty heap and initialize it later at runtime. For that, we add the following lines to our rust_main function:

// in src/lib.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn rust_main(multiboot_information_address: usize) {

[…]

// set up guard page and map the heap pages

memory::init(boot_info);

// initialize the heap allocator

unsafe {

HEAP_ALLOCATOR.lock().init(HEAP_START, HEAP_START + HEAP_SIZE);

}

[…]

}

It is important that we initialize the heap after mapping the heap pages, since the init function writes to the heap memory (the first hole).

Our kernel uses the new allocator now, so we can deallocate memory without leaking it. The example from above should work now without causing an OOM situation:

// in rust_main in src/lib.rs

for i in 0..10000 {

format!("Some String");

}

Performance

The linked list based approach has some performance problems. Each allocation or deallocation might need to scan the complete list of holes in the worst case. However, I think it's good enough for now, since our heap will stay relatively small for the near future. When our allocator becomes a performance problem eventually, we can just replace it with a faster alternative.

Summary

Now we're able to use heap storage in our kernel without leaking memory. This allows us to effectively process dynamic data such as user supplied strings in the future. We can also use Rc and Arc to create types with shared ownership. And we have access to various data structures such as Vec or Linked List, which will make our lives much easier. We even have some well tested and optimized binary heap and B-tree implementations!

TODO: update date