45 KiB

+++ title = "Booting" weight = 2 path = "booting" date = 0000-01-01

[extra] chapter = "Bare Bones" icon = ''' '''

extra_content = ["uefi/index.md"] +++

In this post, we explore the boot process on both BIOS and UEFI-based systems. We combine the minimal kernel created in the previous post with a bootloader to create a bootable disk image. We then show how this image can be started in the QEMU emulator and run on real hardware.

This blog is openly developed on GitHub. If you have any problems or questions, please open an issue there. You can also leave comments at the bottom. The complete source code for this post can be found in the post-02 branch.

The Boot Process

When you turn on a computer, it begins executing firmware code that is stored in motherboard ROM. This code performs a power-on self-test, detects available RAM, and pre-initializes the CPU and other hardware. Afterwards it looks for a bootable disk and starts booting the operating system kernel.

On x86, there are two firmware standards: the “Basic Input/Output System“ (BIOS) and the newer “Unified Extensible Firmware Interface” (UEFI). The BIOS standard is old and outdated, but simple and well-supported on any x86 machine since the 1980s. UEFI, in contrast, is more modern and has much more features, but also more complex.

BIOS

Almost all x86 systems have support for BIOS booting, including most UEFI-based machines that support an emulated BIOS. This is great, because you can use the same boot logic across all machines from the last centuries. The drawback is that the standard is very old, for example the CPU is put into a 16-bit compatibility mode called real mode before booting so that archaic bootloaders from the 1980s would still work. Also, BIOS-compatibility will be slowly removed on newer UEFI machines over the next years (see below).

Boot Process

When you turn on a BIOS-based computer, it first loads the BIOS firmware from some special flash memory located on the motherboard. The BIOS runs self test and initialization routines of the hardware, then it looks for bootable disks. For that it loads the first disk sector (512 bytes) of each disk into memory, which contains the master boot record (MBR) structure. This structure has the following general format:

| Offset | Field | Size |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | bootstrap code | 446 |

| 446 | partition entry 1 | 16 |

| 462 | partition entry 2 | 16 |

| 478 | partition entry 3 | 16 |

| 444 | partition entry 4 | 16 |

| 510 | boot signature | 2 |

The bootstrap code is commonly called the bootloader and responsible for loading and starting the operating system kernel. The four partition entries describe the disk partitions such as the C: partition on Windows. The boot signature field at the end of the structure specifies whether this disk is bootable or not. If it is bootable, the signature field must be set to the magic bytes 0xaa55. It's worth noting that there are many extensions of the MBR format, which for example include a 5th partition entry or a disk signature.

The BIOS itself only cares for the boot signature field. If it finds a disk with a boot signature equal to 0xaa55, it directly passes control to the bootloader code stored at the beginning of the disk. This bootloader is then responsible for multiple things:

- Loading the kernel from disk: The bootloader has to determine the location of the kernel image on the disk and load it into memory.

- Initializing the CPU: As noted above, all

x86_64CPUs start up in a 16-bit real mode to be compatible with older operating systems. So in order to run current 64-bit operating systems, the bootloader needsn to switch the CPU from the 16-bit real mode first to the 32-bit protected mode, and then to the 64-bit long mode, where all CPU registers and the complete main memory are available. - Querying system information: The third job of the bootloader is to query certain information from the BIOS and pass it to the OS kernel. This, for example, includes information about the available main memory and graphical output devices.

- Setting up an execution environment: Kernels are typically stored as normal executable files (e.g. in the ELF or PE format), which require some loading procedure. This includes setting up a call stack and a page table.

Some bootloaders also include a basic user interface for choosing between multiple installed OSs or entering a recovery mode. Since it is not possible to do all that within the available 446 bytes, most bootloaders are split into a small first stage, which is as small as possible, and a second stage, which is subsequently loaded by the first stage.

Writing a BIOS bootloader is cumbersome as it requires assembly language and a lot of non insightful steps like “write this magic value to this processor register”. Therefore we don't cover bootloader creation in this post and instead use the existing bootloader crate to make our kernel bootable. If you are interested in building your own BIOS bootloader: Stay tuned, a set of posts on this topic is already planned!

The Future of BIOS

As noted above, most modern systems still support booting operating systems written for the legacy BIOS firmware for backwards-compatibility. However, there are plans to remove this support soon. Thus, it is strongly recommended to make operating system kernels compatible with the newer UEFI standard too. Fortunately, it is possible to create a kernel that supports booting on both BIOS (for older systems) and UEFI (for modern systems).

UEFI

The Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) replaces the classical BIOS firmware on most modern computers. The specification provides lots of useful features that make bootloader implementations much simpler:

- It supports initializing the CPU directly into 64-bit mode, instead of starting in a DOS-compatible 16-bit mode like the BIOS firmware.

- It understands disk partitions and executable files. Thus it is able to fully load the bootloader from disk into memory (no 512-byte "first stage" is required anymore).

- A standardized specification minimizes the differences between systems. This isn't the case for the legacy BIOS firmware, so that bootloaders often have to try different methods because of hardware differences.

- The specification is independent of the CPU architecture, so that the same interface can be used to boot on

x86_64and e.g.ARMCPUs. - It natively supports network booting without requiring additional drivers.

The UEFI standard also tries to make the boot process safer through a so-called "secure boot" mechanism. The idea is that the firmware only allows loading bootloaders that are signed by a trusted digital signature. Thus, malware should be prevented from compromising the early boot process.

Issues & Criticism

While most of the UEFI specification sounds like a good idea, there are also many issues with the standard. The main issue for most people is the fear that the secure boot mechanism can be used to lock users into the Windows operating system and thus prevent the installation of alternative operating systems such as Linux.

Another point of criticism is that the large number of features make the UEFI firmware very complex, which increases the chance that there are some bugs in the firmware implementation itself. This can lead to security problems because the firmware has complete control over the hardware. For example, a vulnerability in the built-in network stack of an UEFI implementation can allow attackers to compromise the system and e.g. silently observe all I/O data. The fact that most UEFI implementations are not open-source makes this issue even more problematic, since there is no way to audit the firmware code for potential bugs.

While there are open firmware projects such as coreboot that try to solve these problems, there is no way around the UEFI standard on most modern consumer computers. So we have to live with these drawbacks for now if we want to build a widely compatible bootloader and operating system kernel.

Boot Process

The UEFI boot process works in the following way:

- After powering on and self-testing all components, the UEFI firmware starts looking for special bootable disk partitions called EFI system partitions. These partitions must be formatted with the FAT file system and assigned a special ID that indicates them as EFI system partition. The UEFI standard understands both the MBR and GPT partition table formats for this, at least theoretically. In practice, some UEFI implementations seem to directly switch to BIOS-style booting when an MBR partition table is used, so it is recommended to only use the GPT format with UEFI.

- If the firmware finds a EFI system partition, it looks for an executable file named

efi\boot\bootx64.efi(on x86_64 systems) in it. This executable must use the Portable Executable (PE) format, which is common in the Windows world. - It then loads the executable from disk to memory, sets up the execution environment (CPU state, page tables, etc.) in a standardized way, and finally jumps to the entry point of the loaded executable.

From this point on, the loaded executable has control. Typically, this executable is a bootloader that then loads the actual operating system kernel. Theoretically, it would also be possible to let the UEFI firmware load the kernel directly without a bootloader in between, but this would make it more difficult to port the kernel to other architectures.

Bootloaders and kernels typically need additional information about the system, for example the amount of available memory. For this reason, the UEFI firmware passes a pointer to a special system table as an argument when invoking the bootloader entry point function. Using this table, the bootloader can query various system information and even invoke special functions provided by the UEFI firmware, for example for accessing the hard disk.

How we will use UEFI

As it is probably clear at this point, the UEFI interface is very powerful and complex. The wide range of functionality makes it even possible to write an operating system directly as an UEFI application, using the UEFI services provided by the system table instead of creating own drivers. In practice, however, most operating systems use UEFI only for the bootloader since own drivers give you better performance and more control over the system. We will also follow this path for our OS implementation.

To keep this post focused, we won't cover the creation of an UEFI bootloader here. Instead, we will use the already mentioned bootloader crate, which allows loading our kernel on both UEFI and BIOS systems. If you're interested in how to create an UEFI bootloader yourself, check out our extra post about UEFI Booting.

The Multiboot Standard

To avoid that every operating system implements its own bootloader that is only compatible with a single OS, the Free Software Foundation created an open bootloader standard called Multiboot in 1995. The standard defines an interface between the bootloader and operating system, so that any Multiboot compliant bootloader can load any Multiboot compliant operating system on both BIOS and UEFI systems. The reference implementation is GNU GRUB, which is the most popular bootloader for Linux systems.

To make a kernel Multiboot compliant, one just needs to insert a so-called Multiboot header at the beginning of the kernel file. This makes it very easy to boot an OS in GRUB. However, GRUB and the Multiboot standard have some problems too:

- The standard is designed to make the bootloader simple instead of the kernel. For example, the kernel needs to be linked with an adjusted default page size, because GRUB can't find the Multiboot header otherwise. Another example is that the boot information, which is passed to the kernel, contains lots of architecture dependent structures instead of providing clean abstractions.

- The standard supports only the 32-bit protected mode on BIOS systems. This means that you still have to do the CPU configuration to switch to the 64-bit long mode.

- For UEFI systems, the standard provides very little added value as it simply exposes the normal UEFI interface to kernels.

- Both GRUB and the Multiboot standard are only sparsely documented.

- GRUB needs to be installed on the host system to create a bootable disk image from the kernel file. This makes development on Windows or Mac more difficult.

Because of these drawbacks we decided to not use GRUB or the Multiboot standard for this series. However, we plan to add Multiboot support to our bootloader crate, so that it becomes possible to load your kernel on a GRUB system too. If you're interested in writing a Multiboot compliant kernel, check out the first edition of this blog series.

Bootable Disk Image

We now know that most operating system kernels are loaded by bootloaders, which are small programs that initialize the hardware to reasonable defaults, load the kernel from disk, and provide it with some fundamental information about the underlying system. In this section, we will learn how to combine the minimal kernel we created in the previous post with the bootloader crate in order to create a bootable disk image.

The bootloader Crate

Since bootloaders quite complex on their own, we won't create our own bootloader here (but we are planning a separate series of posts on this). Instead, we will boot our kernel using the bootloader crate. This crate supports both BIOS and UEFI booting, provides all the necessary system information we need, and creates a reasonable default execution environment for our kernel. This way, we can focus on the actual kernel design in the following posts instead of spending a lot of time on system initialization.

To use the bootloader crate, we first need to add a dependency on it:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

bootloader = "0.10.1"

For normal Rust crates, this step would be all that's needed for adding them as a dependency. However, the bootloader crate is a bit special. The problem is that it needs access to our kernel after compilation in order to create a bootable disk image. However, cargo has no support for automatically running code after a successful build, so we need some manual build code for this. (There is a proposal for post-build scripts that would solve this issue, but it is not clear yet whether the Cargo team wants to add such a feature.)

Receiving the Boot Information

Before we look into the bootable disk image creation, we update need to update our _start entry point to be compatible with the bootloader crate. As we already mentioned above, bootloaders commonly pass additional system information when invoking the kernel, such as the amount of available memory. The bootloader crate also follows this convention, so we need to update our _start entry point to expect an additional argument.

The bootloader documentation specifies that a kernel entry point should have the following signature:

extern "C" fn(boot_info: &'static mut bootloader::BootInfo) -> ! { ... }

The only difference to our _start entry point is the additional boot_info argument, which is passed by the bootloader crate. This argument is a mutable reference to a bootloader::BootInfo type, which provides various information about the system.

About extern "C" and !

extern "C" and !The extern "C" qualifier specifies that the function should use the same ABI and calling convention as C code. It is common to use this qualifier when communicating across different executables because C has a stable ABI that is guaranteed to never change. Normal Rust functions, on the other hand, don't have a stable ABI, so they might change it the future (e.g. to optimize performance) and thus shouldn't be used across different executables.

The ! return type indicates that the function is diverging, which means that it must never return. The bootloader requires this because its code might no longer be valid after the kernel modified the system state such as the page tables.

While we could simply add the additional argument to our _start function, it would result in very fragile code. The problem is that because the _start function is called externally from the bootloader, no checking of the function signature occurs. So no compilation error occurs, even if the function signature completely changed after updating to a newer bootloader version. At runtime, however, the code would fail or introduce undefined behavior.

To avoid these issues and make sure that the entry point function has always the correct signature, the bootloader crate provides an entry_point macro that provides a type-checked way to define a Rust function as the entry point. This way, the function signature is checked at compile time so that no runtime error can occur.

To use the entry_point macro, we rewrite our entry point function in the following way:

// in src/main.rs

use bootloader::{entry_point, BootInfo};

entry_point!(kernel_main);

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static mut BootInfo) -> ! {

loop {}

}

We no longer need to use extern "C" or no_mangle for our entry point, as the macro defines the actual lower-level _start entry point for us. The kernel_main function is now a completely normal Rust function, so we can choose an arbitrary name for it. Since the signature of the function is enforced by the macro, a compilation error occurs when it e.g. has the wrong argument type.

After adjusting our entry point for the bootloader crate, we can now look into how to create a bootable disk image from our kernel.

Creating a Disk Image

The docs of the bootloader crate describes how to create a bootable disk image for a kernel. The first step is to find the directory where cargo placed the source code of the bootloader dependency. Then, a special build command needs to be executed in that directory, passing the paths to the kernel binary and its Cargo.toml as arguments. This will result in multiple disk image files as output, which can be used to boot the kernel on BIOS and UEFI systems.

A boot crate

Since following these steps manually is cumbersome, we create a script to automate it. For that we create a new boot crate in a subdirectory, in which we will implement the build steps:

cargo new --bin boot

This command creates a new boot subfolder with a Cargo.toml and a src/main.rs in it. Since this new cargo project will be tightly coupled with our main project, it makes sense to combine the two crates as a cargo workspace. This way, they will share the same Cargo.lock for their dependencies and place their compilation artifacts in a common target folder. To create such a workspace, we add the following to the Cargo.toml of our main project:

# in Cargo.toml

[workspace]

members = ["boot"]

After creating the workspace, we can begin the implementation of the boot crate. Note that the crate will be invoked as part as our build process, so it can be a normal Rust executable that runs on our host system. This means that is has a classical main function and can use standard library types such as Path or Command without problems.

Locating the bootloader Source

The first step in creating the bootable disk image is to to locate where cargo put the source code of the bootloader dependency. For that we can use cargo's cargo metadata subcommand, which outputs all kinds of information about a cargo project as a JSON object. Among other things, it contains the manifest path (i.e. the path to the Cargo.toml) of all dependencies, including the bootloader crate.

To keep this post short, we won't include the code to parse the JSON output and to locate the right entry here. Instead, we created a small crate named bootloader-locator that wraps the needed functionality in a simple locate_bootloader function. Let's add that crate as a dependency and use it:

# in boot/Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

bootloader-locator = "0.0.4"

// in boot/src/main.rs

use bootloader_locator::locate_bootloader; // new

pub fn main() {

let bootloader_manifest = locate_bootloader("bootloader").unwrap();

dbg!(bootloader_manifest);

}

The locate_bootloader function takes the name of the bootloader dependency as argument to allow alternative bootloader crates that are named differently. Since the function might fail, we use the unwrap method to panic on an error. Panicking is ok here because the boot crate is only part of our build process.

If you're interested in how the locate_bootloader function works, check out its source code. It first executes the cargo metadata command and parses it's result as JSON using the json crate. Then it traverses the parsed metadata to find the bootloader dependency and return its manifest path.

Let's try to run it to see whether it works. If everything succeeds, the dbg! macro should print the path to the bootloader source code. Note that we need to run the boot binary from the root directory of our workspace, not from within the boot directory. Otherwise the locate_bootloader function would operate on the boot/Cargo.toml, where it won't find a bootloader dependency.

To run the boot crate from our workspace root (i.e. the kernel directory), we can pass a --package argument to cargo run:

> cargo run --package boot

[boot/src/main.rs:5] bootloader_manifest = "/.../.cargo/.../bootloader-.../Cargo.toml"

It worked! We see that the bootloader source code lives somewhere in the .cargo directory in our user directory. By querying the source code for the exact bootloader version that our kernel is using, we ensure that the bootloader and the kernel use the exact same version of the BootInfo type. This is important because the BootInfo type is not stable yet, so undefined behavior can occur when when using different BootInfo versions.

Running the Build Command

The next step is to run the build command of the bootloader. From the bootloader docs we learn that the crate requires the following build command:

cargo builder --kernel-manifest path/to/kernel/Cargo.toml \

--kernel-binary path/to/kernel_bin

In addition, the docs recommend to use the --target-dir and --out-dir arguments when building the bootloader as a dependency to override where cargo places the compilation artifacts.

Let's try to invoke that command from our main function. For that we use the process::Command type of the standard library, which allows us to spawn new processes and wait for their results:

// in boot/src/main.rs

use std::process::Command; // new

pub fn main() {

let bootloader_manifest = locate_bootloader("bootloader").unwrap();

// new code below

let kernel_binary = todo!();

let kernel_manifest = todo!();

let target_dir = todo!();

let out_dir = todo!();

// create a new build command; use the `CARGO` environment variable to

// also support non-standard cargo versions

let mut build_cmd = Command::new(env!("CARGO"));

// pass the arguments

build_cmd.arg("builder");

build_cmd.arg("--kernel-manifest").arg(&kernel_manifest);

build_cmd.arg("--kernel-binary").arg(&kernel_binary);

build_cmd.arg("--target-dir").arg(&target_dir);

build_cmd.arg("--out-dir").arg(&out_dir);

// set the working directory

let bootloader_dir = bootloader_manifest.parent().unwrap();

build_cmd.current_dir(&bootloader_dir);

// run the command

let exit_status = build_cmd.status().unwrap();

if !exit_status.success() {

panic!("bootloader build failed");

}

}

We use the Command::new function to create a new process::Command. Instead of hardcoding the command name "cargo", we use the CARGO environment variable that cargo sets when compiling the boot crate. This way, we ensure that we use the exact same cargo version for compiling the bootloader crate, which is important when using non-standard cargo versions, e.g. through rustup's toolchain override shorthands. Since the environment variable is set at compile time, we use the compiler-builtin env! macro to retrieve its value.

After creating the Command type, we pass all the required arguments by calling the Command::arg method. Most of the paths are still set to todo!() as a placeholder and will be filled out in a moment.

Since the build command needs to be run inside the source directory of the bootloader crate, we use the Command::current_dir method to set the working directory accordingly. We can determine the bootloader_dir path from the bootloader_manifest path by using the Path::parent method. Since not all paths have a parent directory (e.g. the path / has not), the parent() call can fail. However, this should never happen for the bootloader_manifest path, so we use the Option::unwrap method that panics on None.

After setting the arguments and the working directory, we use the Command::status method to execute the command and wait for its exit status. Through the ExitStatus::success method we verify that the command was successful. If not we use the panic! macro to cause a panic.

Filling in the Paths

We still need to fill in the paths we marked as todo! above. We start with the path to the kernel binary:

// in `main` in boot/src/main.rs

use std::path::Path;

// TODO: don't hardcore this

let kernel_binary = Path::new("target/x86_64-blog_os/debug/blog_os").canonicalize().unwrap();

By default, cargo places our compiled kernel executable in a subdirectory of the target folder. The x86_64_blog_os is the name of our target JSON file and the debug indicates that this was a build with debug information and without optimizations. For now we simply hardcode the path to keep things simple, but we will make it more flexible later in this post.

Since we're going to need an absolute path, we use the Path::canonicalize method to get the full path to the file. We use unwrap to panic if the file doesn't exist.

To fill in the other path variables, we utilize another environment variable that cargo passes on build:

// in `main` in boot/src/main.rs

// the path to the root of this crate, set by cargo

let manifest_dir = Path::new(env!("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR"));

// we know that the kernel lives in the parent directory

let kernel_dir = manifest_dir.parent().unwrap();

let kernel_manifest = kernel_dir.join("Cargo.toml");

// use the same target folder for building the bootloader

let target_dir = kernel_dir.join("target");

// place the resulting disk image next to our kernel binary

let out_dir = kernel_binary.parent().unwrap();

The CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR environment variable always points to the boot directory, even if the crate is built from a different directory (e.g. via cargo's --manifest-path argument). This gives use a good starting point for creating the paths we care about since we know that our kernel lives in the parent directory.

From the kernel_dir, we can then construct the kernel_manifest and target_dir paths using the Path::join method. For the out_dir binding, we use the parent directory of the kernel_binary path. This way, the bootloader will create the disk image files next to our kernel executable.

Creating the Disk Images

There is one last step before we can create the bootable disk images: The bootloader build requires the rustup component llvm-tools-preview. To install it, we can either run rustup component add llvm-tools-preview or specify it in our rust-toolchain file:

# in rust-toolchain

[toolchain]

channel = "nightly"

components = ["rust-src", "rustfmt", "clippy", "llvm-tools-preview"]

After that can finally use our boot crate to create some bootable disk images from our kernel:

> cargo kbuild

> cargo run --package boot

We first compile our kernel through cargo kbuild to ensure that the kernel binary is up to date. Then we run our boot crate through cargo run --package boot, which takes the kernel binary and builds the bootloader around it. The result are some disk image files named bootimage-* next to our kernel binary inside target/x86_64-blog_os/debug. Note that the command will only work from the root directory of our project. This is because we hardcoded the kernel_binary path in our main function. We will fix this later in the post, but first it is time to actually run our kernel!

From the bootloader docs, we learn that the bootloader the following disk images:

- A BIOS boot image named

bootimage-bios-<bin_name>.img. - Multiple images suitable for UEFI booting

- An EFI executable named

bootimage-uefi-<bin_name>.efi. - A FAT partition image named

bootimage-uefi-<bin_name>.fat, which contains the EFI executable underefi\boot\bootx64.efi. - A GPT disk image named

bootimage-uefi-<bin_name>.img, which contains the FAT image as EFI system partition.

- An EFI executable named

In general, the .img files are the ones that you want to copy to an USB stick in order to boot from it. The other files are useful for booting the kernel in virtual machines such as QEMU. The <bin_name> placeholder is the binary name of the kernel, i.e. blog_os or the crate name you chose.

Running our Kernel

After creating a bootable disk image for our kernel, we are finally able to run it. Before we learn how to run it on real hardware, we start by running it inside the QEMU system emulator. This has multiple advantages:

- We can't break anything: Our kernel has full hardware access, so that a bug might have serious consequences on read hardware.

- We don't need a separate computer: QEMU runs as a normal program on our development computer.

- The edit-test cycle is much faster: We don't need to copy the disk image to bootable usb stick on every kernel change.

- It's possible to debug our kernel via QEMU's debug tools and GDB.

We will still learn how to boot our kernel on real hardware later in this post, but for now we focus on QEMU. For that you need to install QEMU on your machine as described on the QEMU download page.

Running in QEMU

After installing QEMU, you can run qemu-system-x86_64 --version in a terminal to verify that it is installed. Then you can run the BIOS disk image of our kernel through the following command:

qemu-system-x86_64 -drive \

format=raw,file=target/x86_64-blog_os/debug/bootimage-bios-blog_os.img

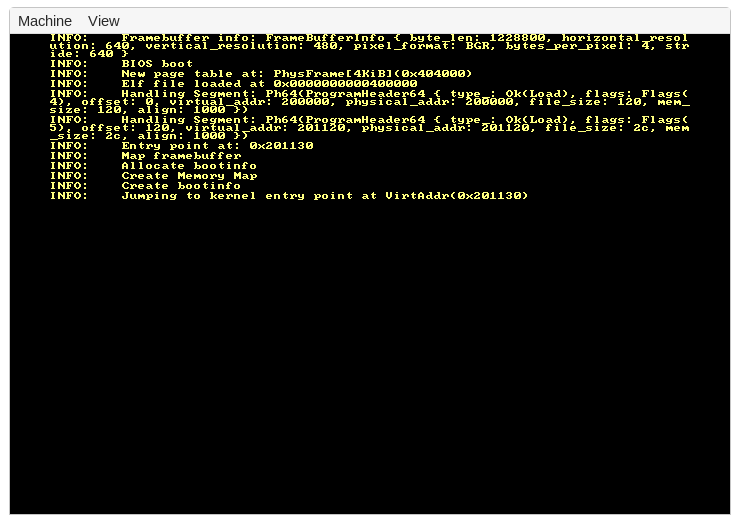

As a result, you should see a window open that looks like this:

This output comes from the bootloader. As we see, the last line is "Jumping to kernel entry point at […]". This is the point where the _start function of our kernel is called. Since we currently only loop {} in that function nothing else happens, so it is expected that we don't see any additional output.

Running the UEFI disk image works in a similar way, but we need to pass some additional files to QEMU to emulate an UEFI firmware. This is necessary because QEMU does not support emulating an UEFI firmware natively. The files that we need are provided by the Open Virtual Machine Firmware (OVMF) project, which is a sub-project of TianoCore and implements UEFI support for virtual machines. Unfortunately, the project is only sparsely documented and does not even have a clear homepage.

The easiest way to work with OVMF is to download pre-built images of the code. We provide such images in the rust-osdev/ovmf-prebuilt repository, which is updated daily from Gerd Hoffman's RPM builds. The compiled OVMF are provided as GitHub releases.

To run our UEFI disk image in QEMU, we need the OVMF_pure-efi.fd file (other files might work as well). After downloading it, we can then run our UEFI disk image using the following command:

qemu-system-x86_64 -drive \

format=raw,file=target/x86_64-blog_os/debug/bootimage-uefi-blog_os.img \

-bios /path/to/OVMF_pure-efi.fd,

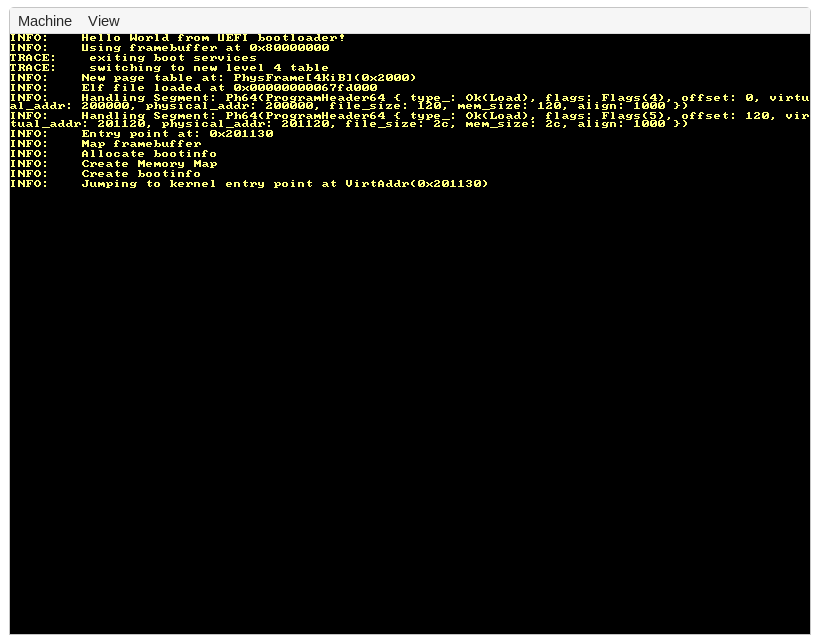

If everything works, this command opens a window with the following content:

The output is a bit different than with the BIOS disk image. Among other things, it explicitly mentions that this is an UEFI boot right on top.

Screen Output

While we see some screen output from the bootloader, our kernel still does nothing. Let's fix this by trying to output something to the screen from our kernel too.

Screen output works through a so-called framebuffer. A framebuffer is a memory region that contains the pixels that should be shown on the screen. The graphics card automatically reads the contents of this region on every screen refresh and updates the shown pixels accordingly.

Since the size, pixel format, and memory location of the framebuffer can vary between different systems, we need to find out these parameters first. The easiest way to do this is to read it from the boot information structure that the bootloader passes as argument to our kernel entry point:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static mut BootInfo) -> ! {

if let Some(framebuffer) = boot_info.framebuffer.as_ref() {

let info = framebuffer.info();

let buffer = framebuffer.buffer();

}

loop {}

}

Even though most systems support a framebuffer, some might not. The BootInfo type reflects this by specifying its framebuffer field as an Option. Since screen output won't be essential for our kernel (there are other possible communication channels such as serial ports), we use an if let statement to run the framebuffer code only if a framebuffer is available.

The FrameBuffer type provides two methods: The [info] method returns a [FrameBufferInfo] instance with all kinds of information about the framebuffer format, including the pixel type and the screen resolution. The [buffer] method returns the actual framebuffer content in form of a mutable byte [slice].

We will look into programming the framebuffer in detail in the next post. For now, let's just try setting the whole screen to some color. For this, we just set every pixel in the byte slice to some fixed value:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static mut BootInfo) -> ! {

if let Some(framebuffer) = boot_info.framebuffer.as_mut() {

for byte in framebuffer.buffer_mut() {

*byte = 0x90;

}

}

loop {}

}

While it depends on the pixel color format how these values are interpreted, the result will likely be some shade of gray since we set the same value for every color channel (e.g. in the RGB color format).

After running cargo kbuild and then our boot script again, we can boot the new version in QEMU. We see that our guess that the whole screen would turn gray was right:

TODO: QEMU screenshot

We finally see some output from our own little kernel!

You can try experimenting with the pixel bytes if you like, for example by increasing the pixel value on each loop iteration:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static mut BootInfo) -> ! {

if let Some(framebuffer) = boot_info.framebuffer.as_mut() {

let mut value = 0x90;

for byte in framebuffer.buffer_mut() {

*byte = value;

value = value.wrapping_add(1);

}

}

loop {}

}

We use the [wrapping_add] method here because Rust panics on implicit integer overflow (at least in debug mode). By adding a prime number, we try to add some variety. The result looks as follows:

TODO

Booting on Real Hardware

TODO

Support for cargo run

- take

kernel_binarypath as argument instead of hardcoding it - set

bootcrate as runner in.cargo/config(for no OS targets only) - add

krunalias

Only create disk images

- Add support for new

--no-runarg tobootcrate - Add

cargo disk-imagealias forcargo run --package boot -- --no-run

OLD

For running bootimage and building the bootloader, you need to have the llvm-tools-preview rustup component installed. You can do so by executing rustup component add llvm-tools-preview.

Real Machine

It is also possible to write it to an USB stick and boot it on a real machine:

> dd if=target/x86_64-blog_os/debug/bootimage-blog_os.img of=/dev/sdX && sync

Where sdX is the device name of your USB stick. Be careful to choose the correct device name, because everything on that device is overwritten.

After writing the image to the USB stick, you can run it on real hardware by booting from it. You probably need to use a special boot menu or change the boot order in your BIOS configuration to boot from the USB stick. Note that it currently doesn't work for UEFI machines, since the bootloader crate has no UEFI support yet.

Using cargo run

To make it easier to run our kernel in QEMU, we can set the runner configuration key for cargo:

# in .cargo/config.toml

[target.'cfg(target_os = "none")']

runner = "bootimage runner"

The target.'cfg(target_os = "none")' table applies to all targets that have set the "os" field of their target configuration file to "none". This includes our x86_64-blog_os.json target. The runner key specifies the command that should be invoked for cargo run. The command is run after a successful build with the executable path passed as first argument. See the [cargo documentation][cargo configuration] for more details.

The bootimage runner command is specifically designed to be usable as a runner executable. It links the given executable with the project's bootloader dependency and then launches QEMU. See the Readme of bootimage for more details and possible configuration options.

Now we can use cargo run to compile our kernel and boot it in QEMU.

What's next?

In the next post, we will explore the VGA text buffer in more detail and write a safe interface for it. We will also add support for the println macro.