142 KiB

+++ title = "Async/Await" weight = 12 path = "async-await" date = 2020-03-27

[extra] chapter = "Multitasking"

Please update this when updating the translation

translation_based_on_commit = "f2966a53489a1c3eff3e5c3c1c82a3febb47569b"

GitHub usernames of the people that translated this post

translators = ["TakiMoysha"]

+++

В этом посте мы рассмотрим кооперативную многозадачность и возможности async/await в Rust. Мы подробно рассмотрим, как async/await работает в Rust, включая трейт Future, преобразование машины состояний и pinning. Затем мы добавим базовую поддержку async/await в наше ядро, by creating an asynchronous keyboard task and a basic executor.

Этот блог открыто разрабатывается на GitHub. Если у вас возникают проблемы или вопросы, пожалуйста, откройте issue. Также вы можете оставлять комментарии внизу. Исходный код этого поста можно найти в post-12 ветку.

Многозадачность

Одной из основных функций возможностей операционных систем является [многозадачность][multitasking], то есть возможность одновременного выполнения нескольких задач. Например, вероятно, пока вы читаете этот пост, у вас открыты другие программы, такие как текстовый редактор или окно терминала. Даже если у вас открыто только одно окно браузера, вероятно, в фоновом режиме выполняются различные задачи по управлению окнами рабочего стола, проверке обновлений или индексированию файлов.

Хотя кажется, что все задачи выполняются параллельно, на одном ядре процессора может выполняться только одна задача за раз. Чтобы создать иллюзию параллельного выполнения задач, операционная система быстро переключается между активными задачами, чтобы каждая из них могла выполнить небольшой прогресс. Поскольку компьютеры работают быстро, мы в большинстве случаев не замечаем этих переключений.

Когда одноядерные центральные процессоры (ЦП) могут выполнять только одну задачу за раз, многоядерные ЦП могут выполнять несколько задач по настоящему параллельно. Например, процессор с 8 ядрами может выполнять 8 задач одновременно. В следующей статье мы расскажем, как настроить многоядерные ЦП. В этой статье для простоты мы сосредоточимся на одноядерных процессорах. (Стоит отметить, что все многоядерные ЦП запускаются с одним активным ядром, поэтому пока мы можем рассматривать их как одноядерные процессоры).

Есть две формы многозадачности: кооперативная (совместная) - требует, чтобы задачи регулярно отдавали контроль над процессором для продвижения других задач; вытесняющая (приоритетная) - использующая функционал операционной системы (ОС) для переключения потоков в произвольные моменты моменты времени через принудительную остановку. Далее мы рассмотрим две формы многозадачности более подробно и обсудим их преимущества и недостатки.

Вытесняющая Многозадачность

Идея заключается в том, что ОС контролирует, когда переключать задачи. Для этого она использует факт того, что при каждом прирывании она восстанавливает контрлоль над ЦП. Это позволяет переключать задачи всякий раз, когда в системе появляется новый ввод. Например, возможность переключать задачи когда двигается мышка или приходят пакеты по сети. ОС также может определять точное время, в течении которого задаче разрешается выполняться, настроив аппаратный таймер на отправку прерывания по истечению этого времени.

На следующем рисунку показан процесс переключения задач при аппаратном прерывании:

На первой строке ЦП выполняет задачу A1 программы A. Все другие задачи приостановлены. На второй строке, наступает аппаратное прерывание. Как описанно в посте Аппаратные Прерывания, ЦП немедленно останавливает выполнение задачи A1 и переходит к обработчику прерываний, определенному в таблице векторов прерываний (Interrupt Descriptor Table, IDT). Благодаря этого обработчику прерывания ОС теперь снова обладает контролем над ЦП, что позволяет ей переключиться на задачу B1 вместо продолжения задачи A1.

Сохранение состояния

Поскольку задачи прерываются в произвольные моменты времени, они могут находиться в середине вычислений. Чтобы иметь возможность возобновить их позже, ОС должна создать копию всего состояния задачи, включая ее стек вызовов и значения всех регистров ЦП. Этот процесс называется переключением контекста.

Поскольку стек вызовов может быть очень большим, операционная система обычно создает отдельный стек вызовов для каждой задачи, вместо того чтобы сохранять содержимое стека вызовов при каждом переключении задач. Такая задача со своим собственным стеком называется потоком выполнения или сокращенно поток. Используя отдельный стек для каждой задачи, при переключении контекста необходимо сохранять только содержимое регистров (включая программный счетчик и указатель стека). Такой подход минимизирует накладные расходы на производительность при переключении контекста, что очень важно, поскольку переключения контекста часто происходят до 100 раз в секунду.

Обсуждение

Основным преимуществом вытесняющей многозадачности является то, что операционная система может полностью контролировать разрешенное время выполнения задачи. Таким образом, она может гарантировать, что каждая задача получит справедливую долю времени процессора, без необходимости полагаться на кооперацию задач. Это особенно важно при выполнении сторонних задач или когда несколько пользователей совместно используют одну систему.

Недостатком вытесняющей многозадачности является то, что каждой задаче требуется собственный стек. По сравнению с общим стеком это приводит к более высокому использованию памяти на задачу и часто ограничивает количество задач в системе. Другим недостатком является то, что ОС всегда должна сохранять полное состояние регистров ЦП при каждом переключении задач, даже если задача использовала только небольшую часть регистров.

Вытесняющая многозадачность и потоки - фундаментальные компонтенты ОС, т.к. они позволяют запускать недоверенные программы в userspace (run untrusted userspace programs) . Мы подробнее обсудим эти концепции в будущийх постах. Однако сейчас, мы сосредоточимся на кооперативной многозадачности, которая также предоставляет полезные возможности для нашего ядра.

Кооперативная Многозадачность

Вместо принудительной остановки выполняющихся задач в произвольные моменты времени, кооперативная многозадачность позволяет каждой задаче выполняться до тех пор, пока она добровольно не уступит контроль над ЦП. Это позволяет задачам самостоятельно приостанавливаться в удобные моменты времени, например, когда им нужно ждать операции ввода-вывода.

Кооперативная многозадачность часто используется на языковом уровне, например в виде сопрограмм или async/await. Идея в том, что программист или компилятор вставляет в программу операции yield, которые отказываются от управления ЦП и позволяют выполняться другим задачам. Например, yield может быть вставлен после каждой итерации сложного цикла.

Часто кооперативную многозадачность совмещают с асинхронными операциями. Вместо того чтобы ждать завершения операции и препятствовать выполнению других задач в это время, асинхронные операции возвращают статус «не готов», если операция еще не завершена. В этом случае ожидающая задача может выполнить операцию yield, чтобы другие задачи могли выполняться.

Сохранение состояния

Поскольку задачи сами определяют точки паузы, им не нужно, чтобы ОС сохраняла их состояние. Вместо этого они могут сохранять то состояние, которое необходимо для продолжения работы, что часто приводит к улучшению производительности. Например, задаче, которая только что завершила сложные вычисления, может потребоваться только резервное копирование конечного результата вычислений, т.к. промежуточные результаты ей больше не нужны.

Реализации кооперативных задач, поддерживаемые языком, часто даже могут сохранять необходимые части стека вызовов перед приостановкой. Например, реализация async/await в Rust сохраняет все локальные переменные, которые еще нужны, в автоматически сгенерированной структуре (см. ниже). Благодаря резервному копированию соответствующих частей стека вызовов перед приостановкой все задачи могут использовать один стек вызовов, что приводит к значительному снижению потребления памяти на задачу. Это позволяет создавать практически любое количество кооперативных задач без исчерпания памяти.

Обсуждение

Недостатком кооперативной многозадачности является то, что некооперативная задача может потенциально выполняться в течение неограниченного времени. Таким образом, вредоносная или содержащая ошибки задача может помешать выполнению других задач и замедлить или даже заблокировать работу всей системы. По этой причине кооперативная многозадачность должна использоваться только в том случае, если известно, что все задачи будут взаимодействовать друг с другом. В качестве противоположного примера можно привести то, что не стоит полагаться на взаимодействие произвольных программ пользовательского уровня в операционной системе.

Однако высокая производительность и преимущества кооперативной многозадачности в плане памяти делают ее хорошим подходом для использования внутри программы, особенно в сочетании с асинхронными операциями. Поскольку ядро операционной системы является программой, критичной с точки зрения производительности, которая взаимодействует с асинхронным оборудованием, кооперативная многозадачность кажется хорошим подходом для реализации параллелизма.

Async/Await в Rust

Rust предоставляет отличную поддержку кооперативной многозадачности в виде async/await. Прежде чем мы сможем изучить, что такое async/await и как оно работает, нам необходимо понять, как работают futures и асинхронное программирование в Rust.

Futures

Future представляет значение, которое может быть еще недоступно. Это может быть, например, целое число, вычисляемое другой задачей, или файл, загружаемый из сети. Вместо того, чтобы ждать, пока значение станет доступным, futures позволяют продолжить выполнение до тех пор, пока значение не понадобится.

Пример

Концепцию future лучше всего проиллюстрировать небольшим примером:

Эта диаграмма последовательности показывает функцию main, которая считывает файл из файловой системы, а затем вызывает функцию foo. Этот процесс повторяется дважды: один раз с синхронным вызовом read_file и один раз с асинхронным вызовом async_read_file.

При синхронном вызове функция main должна ждать, пока файл не будет загружен из файловой системы. Только после этого она может вызвать функцию foo, которая требует от нее снова ждать результата.

При асинхронном вызове async_read_file файловая система напрямую возвращает будущее значение и загружает файл асинхронно в фоновом режиме. Это позволяет функции main вызвать foo гораздо раньше, которая затем выполняется параллельно с загрузкой файла. В этом примере загрузка файла даже заканчивается до возврата foo, поэтому main может напрямую работать с файлом без дальнейшего ожидания после возврата foo.

Futures в Rust

В Rust, futures представленны трейтом Future, который выглядит так:

pub trait Future {

type Output;

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output>;

}

Ассоциированный тип Output определяет тип асинхронного значения. Например, функция async_read_file на приведенной выше диаграмме вернет экземпляр Future с Output, установленным как File.

Метод poll позволяет проверить, доступно ли значение. Он возвращает перечисление Poll, которое выглядит следующим образом:

pub enum Poll<T> {

Ready(T),

Pending,

}

Когда значение уже доступно (например, файл был полностью прочитан с диска), оно возвращается, обернутое в вариант Ready. Иначе возвращается вариант Pending, который сигнализирует вызывающему, что значение еще не доступно.

Метод poll принимает два аргумента: self: Pin<&mut Self> и cx: &mut Context. Первый аргумент ведет себя аналогично обычной ссылке &mut self, за исключением того, что значение Self pinned к своему месту в памяти. Понять Pin и его необходимость сложно, не понимая сначала, как работает async/await. Поэтому мы объясним это позже в этом посте.

Параметр cx: &mut Context нужен для передачи экземпляра Waker в асинхронную задачу, например, загрузку файловой системы. Этот Waker позволяет асинхронной задаче сообщать о том, что она (или ее часть) завершена, например, что файл был загружен с диска. Поскольку основная задача знает, что она будет уведомлена, когда Future будет готов, ей не нужно повторно вызывать poll. Мы объясним этот процесс более подробно позже в этом посте, когда будем реализовывать наш собственный тип waker.

Работа с Futures

Теперь мы знаем, как определяются футуры, и понимаем основную идею метода poll. Однако мы все еще не знаем, как эффективно работать с футурами. Проблема в том, что они представляют собой результаты асинхронных задач, которые могут быть еще недоступны. На практике, однако, нам часто нужны эти значения непосредственно для дальнейших вычислений. Поэтому возникает вопрос: как мы можем эффективно получить значение, когда оно нам нужно?

Ожидание Futures

Один из возможных ответов — дождаться, пока будущее станет реальностью. Это может выглядеть примерно так:

let future = async_read_file("foo.txt");

let file_content = loop {

match future.poll(…) {

Poll::Ready(value) => break value,

Poll::Pending => {}, // ничего не делать

}

}

Здесь мы активно ждем футуру, вызывая poll снова и снова в цикле. Аргументы poll опущены, т.к. здесь они не имеют значения. Хотя это решение работает, оно очень неэффективно, потому что мы занимаем CPU до тех пор, пока значение не станет доступным.

Более эффективным подходом может быть блокировка текущего потока до тех пор, пока футура не станет доступной. Конечно, это возможно только при наличии потоков, поэтому это решение не работает для нашего ядра, по крайней мере, пока. Даже в системах, где поддерживается блокировка, она часто нежелательна, поскольку превращает асинхронную задачу в синхронную, тем самым сдерживая потенциальные преимущества параллельных задач в плане производительности.

Комбинаторы Future

Альтернативой ожиданию является использование комбинаторов future. Комбинаторы future - это методы вроде map, которые позволяют объединять и связывать future между собой, аналогично методам трейта Iterator. Вместо того чтобы ожидать выполнения future, эти комбинаторы сами возвращают future, которые применяет операцию преобразования при вызове poll.

Например, простой комбинатор string_len для преобразования Future<Output = String> в Future<Output = usize> может выглядеть так:

struct StringLen<F> {

inner_future: F,

}

impl<F> Future for StringLen<F> where F: Future<Output = String> {

type Output = usize;

fn poll(mut self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<T> {

match self.inner_future.poll(cx) {

Poll::Ready(s) => Poll::Ready(s.len()),

Poll::Pending => Poll::Pending,

}

}

}

fn string_len(string: impl Future<Output = String>)

-> impl Future<Output = usize>

{

StringLen {

inner_future: string,

}

}

// Использование

fn file_len() -> impl Future<Output = usize> {

let file_content_future = async_read_file("foo.txt");

string_len(file_content_future)

}

Этот код не совсем корректен, потому что не учитывает pinning, но он подходит для примера. Основная идея в том, что функция string_len оборачивает переданный экземпляр Future в новую структуру StringLen, которая также реализует Future. При опросе обёрнутого future опрашивается внутренний future. Если значение ещё не готово, из обёрнутого future также возвращается Poll::Pending. Если значение готово, строка извлекается из варианта Poll::Ready, вычисляется её длина, после чего результат снова оборачивается в Poll::Ready и возвращается.

С помощью функции string_len можно вычислить длину асинхронной строки, не дожидаясь её завершения. Поскольку функция снова возвращает Future, вызывающий код не может работать с возвращённым значением напрямую, а должен использовать комбинаторы. Таким образом, весь граф вызовов становится асинхронным, и в какой-то момент (например, в основной функции) можно эффективно ожидать завершения нескольких future одновременно.

Так как ручное написание функций-комбинаторов сложно, они обычно предоставляются библиотеками. Стандартная библиотека Rust пока не содержит методов-комбинаторов, но полуофициальная (и совместимая с no_std) библиотека futures предоставляет их. Её трейт [FutureExt] включает высокоуровневые методы-комбинаторы, такие как [map] или [then], которые позволяют манипулировать результатом с помощью произвольных замыканий.

Преимущества

Большое преимущество future комбинаторов (future combinators) в том, что они сохраняют асинхронность. В сочетании с асинхронными интерфейсами ввода-вывода такой подход может обеспечить очень высокую производительность. То, что future кобинаторы реализованы как обычные структуры с имплементацией трейтов, позволяет компилятору чрезвычайно оптимизировать их. Подробнее см. в посте Futures с нулевой стоимостью в Rust, где было объявлено о добавлении futures в экосистему Rust.

Недостатки

Хотя future комбинаторы позволяют писать очень эффективный код, их может быть сложно использовать в некоторых ситуациях из-за системы типов и интерфейса на основе замыканий. Например, рассмотрим такой код:

fn example(min_len: usize) -> impl Future<Output = String> {

async_read_file("foo.txt").then(move |content| {

if content.len() < min_len {

Either::Left(async_read_file("bar.txt").map(|s| content + &s))

} else {

Either::Right(future::ready(content))

}

})

}

Здесь мы читаем файл foo.txt, а затем используем комбинатор [then], чтобы связать вторую футуру на основе содержимого файла. Если длина содержимого меньше заданного min_len, мы читаем другой файл bar.txt и добавляем его к content с помощью комбинатора [map]. В противном случае возвращаем только содержимое foo.txt.

Нам нужно использовать ключевое слово [move] для замыкания, передаваемого в then, иначе возникнет ошибка времени жизни (lifetime) для min_len. Причина использования обёртки Either заключается в том, что блоки if и else всегда должны возвращать значения одного типа. Поскольку в блоках возвращаются разные типы будущих значений, нам необходимо использовать обёртку, чтобы привести их к единому типу. Функция ready оборачивает значение в будущее, которое сразу готово к использованию. Здесь она необходима, потому что обёртка Either ожидает, что обёрнутое значение реализует Future.

Как можно догадаться, такой подход быстро приводит к очень сложному коду, особенно в крупных проектах. Ситуация ещё больше усложняется, если задействованы заимствования (borrowing) и разные времена жизни (lifetimes). Именно поэтому в Rust было вложено много усилий для добавления поддержки async/await — с целью сделать написание асинхронного кода радикально проще.

Паттерн Async/Await

Идея async/await заключается в том, чтобы позволить программисту писать код, который выглядит как обычный синхронный код, но превращается в асинхронный код компилятором. Это работает на основе двух ключевых слов async и await. Ключевое слово async можно использовать в сигнатуре функции для превращения синхронной функции в асинхронную функцию, возвращающую future:

async fn foo() -> u32 {

0

}

// примерно переводится компилятором в:

fn foo() -> impl Future<Output = u32> {

future::ready(0)

}

Одного этого ключевого слова недостаточно. Однако внутри функций async можно использовать ключевое слово await, чтобы получить асинхронное значение future:

async fn example(min_len: usize) -> String {

let content = async_read_file("foo.txt").await;

if content.len() < min_len {

content + &async_read_file("bar.txt").await

} else {

content

}

}

В данном примере async_read_file — это асинхронная функция, возвращающая будущее строки.

async fn example(min_len: usize) -> String {

let content = async_read_file("foo.txt").await;

if content.len() < min_len {

content + &async_read_file("bar.txt").await

} else {

content

}

}

Эта ф-ция - прямой перевод example написанной выше, которая использовала комбинаторные ф-ции. Используя оператор .await, мы можем получить значение future без необходимости использования каких-либо замыканий или типов Either. В результате, мы можем писать наш код так же, как если бы это был обычный синхронный код, с той лишь разницей, что это все еще асинхронный код.

Преобразованиe Конечных Автоматов (Машина состояний)

За кулисами компилятор преобразует тело ф-ции async в state machine с каждым вызовом .await, представляющим собой разное состояние. Для вышеуказанной ф-ции example, компилятор создает state machine с четырьмя состояниями.

Каждое состояние представляет собой точку остановки в функции. Состояния "Start" и "End", указывают на начало и конец выполнения ф-ции. Состояние "waiting on foo.txt" - функция в данный момент ждёт первого результата async_read_file. Аналогично, состояние "waiting on bar.txt" представляет остановку, когда ф-ция ожидает второй результат async_read_file.

Конечный автомат реализует trait Future делая каждый вызов poll возможным переход между состояниями:

Диаграмма использует стрелки для представления переключений состояний и ромбы для представления альтернативных путей. Например, если файл foo.txt не готов, то мы используется путь "no" переходя в состояние "waiting on foo.txt". Иначе, используется путь "да". Где маленький красный комб без подписи - ветвь ф-ции exmple, где if content.len() < 100.

Мы видим, что первый вызов poll запускает функцию и она выполняться до тех пор, пока у футуры не будет результата. Если все футуры на пути готовы, ф-ция может выполниться до состояния "end" , то есть вернуть свой результат, завернутый в Poll::Ready. В противном случае конечный автомат переходит в состояние ожидания и возвращает Poll::Pending. При следующем вызове poll машина состояний начинает с последнего состояния ожидания и повторяет последнюю операцию.

Сохранение состояния

Для продолжнеия работы с последнего состояния ожидания, автомат должен отслеживать текущее состояние внутри себя. Еще, он должен сохранять все переменные, которые необходимы для продолжнеия выполнения при следующем вызове poll. Здесь компилятор действительно может проявить себя: зная, когда используются те или иные переменные, он может автоматически создавать структуры с точным набором требуемых переменных.

Например, компилятор генерирует структуры для вышеприведенной ф-ции example:

// снова `example` что бы вам не пришлось прокручивать вверх

async fn example(min_len: usize) -> String {

let content = async_read_file("foo.txt").await;

if content.len() < min_len {

content + &async_read_file("bar.txt").await

} else {

content

}

}

// компиялтор генерирует структуры

struct StartState {

min_len: usize,

}

struct WaitingOnFooTxtState {

min_len: usize,

foo_txt_future: impl Future<Output = String>,

}

struct WaitingOnBarTxtState {

content: String,

bar_txt_future: impl Future<Output = String>,

}

struct EndState {}

В состояниях "start" и "waiting on foo.txt" необходимо сохранить параметр min_len для последующего сравнения с content.len(). Состояние "waiting on foo.txt" дополнительно содержит foo_txt_future, представляющий future возвращаемое вызовом async_read_file. Этe футуру нужно опросить снова, когда автомат продолжит свою работу, поэтому его нужно сохранить.

Состояние "waiting on bar.txt" содержит переменную content для последующей конкатенации строк при загрузке файла bar.txt. Оно также хранит bar_txt_future, представляющее текущую загрузку файла bar.txt. Эта структура не содержит переменную min_len, потому что она уже не нужна после проверки длины строки content.len(). В состоянии "end", в структуре ничего нет, т.к. ф-ция завершилась полностью.

Учтите, что приведенный здесь код - это только пример того, какая структура может быть сгенерирована компилятором Имена структур и расположение полей - детали реализации и могут отличаться.

Полный Конечный Автомат

При этом точно сгенерированный код компилятора является деталью реализации, это помогает понять, представив, как могла бы выглядеть машина состояний для функции example. Мы уже определили структуры, представляющие разные состояния и содержащие необходимые переменные. Чтобы создать машину состояний на их основе, мы можем объединить их в enum:

enum ExampleStateMachine {

Start(StartState),

WaitingOnFooTxt(WaitingOnFooTxtState),

WaitingOnBarTxt(WaitingOnBarTxtState),

End(EndState),

}

Мы определяем отдельный вариант перечисления (enum) для каждого состояния и добавляем соответствующую структуру состояния в каждый вариант как поле. Чтобы реализовать переходы между состояниями, компилятор генерирует реализацию trait'а Future на основе функции example:

impl Future for ExampleStateMachine {

type Output = String; // возвращает тип из `example`

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output> {

loop {

match self { // TODO: handle pinning

ExampleStateMachine::Start(state) => {…}

ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnFooTxt(state) => {…}

ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnBarTxt(state) => {…}

ExampleStateMachine::End(state) => {…}

}

}

}

}

Тип Output будущего равен String, потому что это тип возвращаемого значения функции example. Для реализации метода poll мы используем условную инструкцию match на текущем состоянии внутри цикла. Идея в том, что мы переходим к следующему состоянию, пока это возможно, и явно возвращаем Poll::Pending, когда мы не можем продолжить.

Для упрощения мы представляем только упрощенный код и не обрабатываем закрепление, владения, lifetimes, и т.д. Поэтому этот и следующий код должны быть восприняты как псевдокод и не использоваться напрямую. Конечно, реальный генерируемый компилятором код обрабатывает всё верно, хотя возможно это будет сделано по-другому.

Чтобы сохранить примеры кода маленькими, мы представляем код для каждого варианта match отдельно. Начнем с состояния Start:

ExampleStateMachine::Start(state) => {

// из тела `example`

let foo_txt_future = async_read_file("foo.txt");

// операция`.await`

let state = WaitingOnFooTxtState {

min_len: state.min_len,

foo_txt_future,

};

*self = ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnFooTxt(state);

}

Машина состояний находится в состоянии Start, когда она прямо в начале функции. В этом случае выполняем весь код из тела функции example до первого .await. Чтобы обработать операцию .await, мы меняем состояние машины на WaitingOnFooTxt, которое включает в себя построение структуры WaitingOnFooTxtState.

Пока match self {…} выполняется в цилке, выполнение прыгает к WaitingOnFooTxt:

ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnFooTxt(state) => {

match state.foo_txt_future.poll(cx) {

Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending,

Poll::Ready(content) => {

// из тела `example`

if content.len() < state.min_len {

let bar_txt_future = async_read_file("bar.txt");

// операция `.await`

let state = WaitingOnBarTxtState {

content,

bar_txt_future,

};

*self = ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnBarTxt(state);

} else {

*self = ExampleStateMachine::End(EndState);

return Poll::Ready(content);

}

}

}

}

В этом варианте match, вначале мы вызываем функцию poll для foo_txt_future. Если она не готова, мы выходим из цикла и возвращаем Poll::Pending. В этом случае self остается в состоянии WaitingOnFooTxt, следующий вызов функции poll на машине состояний попадёт в тот же match и повторит проверку готовности foo_txt_future.

Когда foo_txt_future готов, мы присваиваем результат переменной content и продолжаем выполнять код функции example: Если content.len() меньше сохранённого в структуре состояния min_len, файл bar.txt читается асинхронно. Мы ещё раз переводим операцию .await в изменение состояния, теперь в состояние WaitingOnBarTxt. Следуя за выполнением match внутри цикла, выполнение прямо переходит к варианту match для нового состояния позже, где проверяется готовность bar_txt_future.

В случае входа в ветку else, более никаких операций .await не происходит. Мы достигаем конца функции и возвращаем content обёрнутую в Poll::Ready. Также меняем текущее состояние на End.

Код для состояния WaitingOnBarTxt выглядит следующим образом:

ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnBarTxt(state) => {

match state.bar_txt_future.poll(cx) {

Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending,

Poll::Ready(bar_txt) => {

*self = ExampleStateMachine::End(EndState);

// из тела `example`

return Poll::Ready(state.content + &bar_txt);

}

}

}

Аналогично состоянию WaitingOnFooTxt, мы начинаем с проверки готовности bar_txt_future. Если она ещё не готова, мы выходим из цикла и возвращаем Poll::Pending. В противном случае, мы можем выполнить последнюю операцию функции example: конкатенацию переменной content с результатом футуры. Обновляем машину состояний в состояние End и затем возвращаем результат обёрнутый в Poll::Ready.

В итоге, код для End состояния выглядит так:

ExampleStateMachine::End(_) => {

panic!("poll вызван после возврата Poll::Ready");

}

Футуры не должны повторно проверяться после того, как они вернули Poll::Ready, поэтому паникуем, если вызвана функция poll, когда мы уже находимся в состоянии End.

Теперь мы знаем, что сгенерированная машина состояний и ее реализация интерфейса Future могла бы выглядеть так. На практике компилятор генерирует код по-другому. (Если вас заинтересует, то реализация ныне основана на корутинах, но это только деталь имплементации.)

Последняя часть загадки – сгенерированный код для самой функции example. Помните, что заголовок функции был определён следующим образом:

async fn example(min_len: usize) -> String

Теперь, когда весь функционал реализуется машиной состояний, единственное, что ф-ция должна сделать - это инициализировать эту машику и вернуть ее. Сгенерированный код для этого может выглядеть следующим образом:

fn example(min_len: usize) -> ExampleStateMachine {

ExampleStateMachine::Start(StartState {

min_len,

})

}

Функция больше не имеет модификатора async, поскольку теперь явно возвращает тип ExampleStateMachine, который реализует трейт Future. Как ожидалось, машина состояний создается в состоянии start и соответствующая ему структура состояния инициализируется параметром min_len.

Заметьте, что эта функция не запускает выполнение машины состояний. Это фундаментальное архитектурное решение для футур в Rust: они ничего не делают, пока не будет произведена первая проверка на готовность.

Закрепление (Pinning)

Мы уже несколько раз столкнулись с понятием закрепления (pinnig) в этом посте. Наконец, время чтобы изучить, что такое закрепление и почему оно необходимо.

Самоссылающиеся структуры

Как объяснялось выше, переходы конечных автоматов хранят локальные переменные для каждой точки остановки в структуре. Для простых примеров, как наш example функции, это было просто и не привело к никаким проблемам. Однако делаются сложнее, когда переменные ссылаются друг на друга. Например, рассмотрите следующую функцию:

async fn pin_example() -> i32 {

let array = [1, 2, 3];

let element = &array[2];

async_write_file("foo.txt", element.to_string()).await;

*element

}

Эта функция создает маленький array с содержимым 1, 2, и 3. Затем она создает ссылку на последний элемент массива и хранит ее в переменной element. Далее, асинхронно записывает число, преобразованное в строку, в файл foo.txt. В конце, возвращает число, ссылка на которое хранится в element.

Следуя своей единственной операции await, машина состояний состоит из трех состояний: start, end и "waiting on write". Функция не принимает аргументов, поэтому структура для начального состояния пуста. Как обычно, структура для конечного состояния также пустая, поскольку функция завершена на этом этапе. Структура для "waiting on write" более интересна:

struct WaitingOnWriteState {

array: [1, 2, 3],

element: 0x1001c, // адрес последнего элемента в array

}

Мы должны хранить как array, так и element потому что element требуется для значения возврата, а array ссылается на element. Следовательно, element является указателем (pointer) (адресом памяти), который хранит адрес ссылаемого элемента. В этом примере мы использовали 0x1001c в качестве примера адреса, в реальности он должен быть адресом последнего элемента поля array, что зависит от места расположения структуры в памяти. Структуры с такими внутренними указателями называются самоссылочными (self-referential) структурами, потому что они ссылаются на себя из одного из своих полей.

Проблемы с Самоссылочными Структурами

Внутренний указатель нашей самоссылочной структуры приводит к базовой проблеме, которая становится очевидной, когда мы посмотрим на её раскладку памяти:

Поле array начинается в адресе 0x10014, а поле element - в адресе 0x10020. Оно указывает на адрес 0x1001c, потому что последний элемент массива находится там. В этот момент все ещё в порядке. Однако проблема возникает, когда мы перемещаем эту структуру на другой адрес памяти:

Мы переместили структуру немного так, чтобы она теперь начиналась в адресе 0x10024. Это могло произойти, например, когда мы передаем структуру как аргумент функции или присваиваем ей другое переменной стека. Проблема заключается в том, что поле element все ещё указывает на адрес 0x1001c, хотя последний элемент массива теперь находится в адресе 0x1002c. Поэтому указатель висит, с результатом неопределённого поведения на следующем вызове poll.

Возможные решения

Существует три основных подхода к решению проблемы висящих указателей (dangling pointers):

- Обновление указателя при перемещении: Идея состоит в обновлении внутреннего указателя при каждом перемещении структуры в памяти, чтобы она оставалась действительной после перемещения. Однако этот подход требует значительных изменений в Rust, которые могут привести к потенциальным значительным потерям производительности. Причина заключается в том, что необходимо каким-то образом отслеживать тип всех полей структуры и проверять на каждом операции перемещения, требуется ли обновление указателя.

- Хранение смещения (offset) вместо самоссылающихся ссылок: Чтобы избежать необходимости обновления указателей, компилятор мог бы попытаться хранить самоссы ссылки в форме смещений от начала структуры вместо прямых ссылок. Например, поле

elementвышеупомянутойWaitingOnWriteStateструктуры можно было бы хранить в виде поляelement_offsetc значением 8, потому что элемент массива, на который указывает ссылка, находится за 8 байтов после начала структуры. Смещение остается неизменным при перемещении структуры, так что не требуются обновления полей. Проблема с этим подходом в том, что требуется, чтобы компилятор обнаружил всех самоссылок. Это невозможно на этапе компилящии потому, что значение ссылки может зависеть от ввода пользователя, так что нам потребуется система анализа ссылок и корректная генерация состояния для структур во время исполнения. Это приведёт к дополнительным расходам времени на выполнение, а также предотвратит определённые оптимизации компилятора, что приведёт к еще большим потерям производительности. - Запретить перемещать структуру: Мы увидели выше, что висящий указатель возникает только при перемещении структуры в памяти. Запретив все операции перемещения для самоссылающихся структур, можно избежать этой проблемы. Большое преимущество этого подхода состоит в том, что он можно реализовать на уровне системы типов без дополнительных расходов времени выполнения. Недостаток заключается в том, что оно возлагает на программиста обязанности по обработке перемещений самоссылающихся структур.

Rust выбрал третий подход из-за принципа предоставления бесплатных абстракций (zero cost abstractions), что означает, что абстракции не должны накладывать дополнительные расходы времени выполнения. API pinning предлагалось для решения этой проблемы в RFC 2349 (https://github.com/rust-lang/rfcs/blob/master/text/2349-pin.md). В следующем разделе мы дадим краткий обзор этого API и объясним, как оно работает с async/await и futures.

Значения на Куче (Heap)

Первый наблюдение состоит в том, что значения, выделенные на [куче], обычно имеют фиксированный адрес памяти. Они создаются с помощью вызова allocate и затем ссылаются на тип указателя, такой как Box<T>. Хотя перемещение указательного типа возможно, значение кучи, которое указывает на него, остается в том же адресе памяти до тех пор, пока оно не будет освобождено с помощью вызова deallocate еще раз.

Используя аллокацию по куче, можно попытаться создать самоссылающуюся структуру:

fn main() {

let mut heap_value = Box::new(SelfReferential {

self_ptr: 0 as *const _,

});

let ptr = &*heap_value as *const SelfReferential;

heap_value.self_ptr = ptr;

println!("heap value at: {:p}", heap_value);

println!("internal reference: {:p}", heap_value.self_ptr);

}

struct SelfReferential {

self_ptr: *const Self,

}

Мы создаем простую структуру с названием SelfReferential, которая содержит только одно поле c указателем. Во-первых, мы инициализируем эту структуру с пустым указателем и затем выделяем ее на куче с помощью Box::new. Затем мы определяем адрес кучи для выделенной структуры и храним его в переменной ptr. В конце концов, мы делаем структуру самоссылающейся, назначив переменную ptr полю self_ptr.

Когда мы запускаем этот код в песочнице, мы видим, что адрес на куче и внутренний указатель равны, что означает, что поле self_ptr валидное. Поскольку переменная heap_value является только указателем, перемещение его (например, передачей в функцию) не изменяет адрес самой структуры, поэтому self_ptr остается действительным даже при перемещении указателя.

Тем не менее, все еще есть путь сломать этот пример: мы можем выйти из Box<T> или изменить содержимое:

let stack_value = mem::replace(&mut *heap_value, SelfReferential {

self_ptr: 0 as *const _,

});

println!("value at: {:p}", &stack_value);

println!("internal reference: {:p}", stack_value.self_ptr);

Мы используем функцию mem::replace, чтобы заменить значение, выделенное в куче, новым экземпляром структуры. Это позволяет нам переместить исходное значение heap_value в стек, в то время как поле self_ptr структуры теперь является висящим указателем, который по-прежнему указывает на старый адрес в куче. Когда вы запустите пример в песочнице, вы увидите, что строки «value at:» и «internal reference:», показывают разные указатели. Таким образом, выделение значения в куче недостаточно для обеспечения безопасности самоссылок.

Основная проблема, которая привела к вышеуказанной ошибке, заключается в том, что Box<T> позволяет нам получить ссылку &mut T на значение, выделенное в куче. Эта ссылка &mut позволяет использовать такие методы, как mem::replace или mem::swap, для аннулирования значения, выделенного в куче. Чтобы решить эту проблему, мы должны предотвратить создание ссылок &mut на самореференциальные структуры.

Pin<Box<T>> and Unpin

The pinning API provides a solution to the &mut T problem in the form of the Pin wrapper type and the Unpin marker trait. The idea behind these types is to gate all methods of Pin that can be used to get &mut references to the wrapped value (e.g. get_mut or deref_mut) on the Unpin trait. The Unpin trait is an auto trait, which is automatically implemented for all types except those that explicitly opt-out. By making self-referential structs opt-out of Unpin, there is no (safe) way to get a &mut T from a Pin<Box<T>> type for them. As a result, their internal self-references are guaranteed to stay valid.

As an example, let's update the SelfReferential type from above to opt-out of Unpin:

use core::marker::PhantomPinned;

struct SelfReferential {

self_ptr: *const Self,

_pin: PhantomPinned,

}

We opt-out by adding a second _pin field of type PhantomPinned. This type is a zero-sized marker type whose only purpose is to not implement the Unpin trait. Because of the way auto traits work, a single field that is not Unpin suffices to make the complete struct opt-out of Unpin.

The second step is to change the Box<SelfReferential> type in the example to a Pin<Box<SelfReferential>> type. The easiest way to do this is to use the Box::pin function instead of Box::new for creating the heap-allocated value:

let mut heap_value = Box::pin(SelfReferential {

self_ptr: 0 as *const _,

_pin: PhantomPinned,

});

In addition to changing Box::new to Box::pin, we also need to add the new _pin field in the struct initializer. Since PhantomPinned is a zero-sized type, we only need its type name to initialize it.

When we try to run our adjusted example now, we see that it no longer works:

error[E0594]: cannot assign to data in a dereference of `std::pin::Pin<std::boxed::Box<SelfReferential>>`

--> src/main.rs:10:5

|

10 | heap_value.self_ptr = ptr;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ cannot assign

|

= help: trait `DerefMut` is required to modify through a dereference, but it is not implemented for `std::pin::Pin<std::boxed::Box<SelfReferential>>`

error[E0596]: cannot borrow data in a dereference of `std::pin::Pin<std::boxed::Box<SelfReferential>>` as mutable

--> src/main.rs:16:36

|

16 | let stack_value = mem::replace(&mut *heap_value, SelfReferential {

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ cannot borrow as mutable

|

= help: trait `DerefMut` is required to modify through a dereference, but it is not implemented for `std::pin::Pin<std::boxed::Box<SelfReferential>>`

Both errors occur because the Pin<Box<SelfReferential>> type no longer implements the DerefMut trait. This is exactly what we wanted because the DerefMut trait would return a &mut reference, which we wanted to prevent. This only happens because we both opted-out of Unpin and changed Box::new to Box::pin.

The problem now is that the compiler does not only prevent moving the type in line 16, but also forbids initializing the self_ptr field in line 10. This happens because the compiler can't differentiate between valid and invalid uses of &mut references. To get the initialization working again, we have to use the unsafe get_unchecked_mut method:

// safe because modifying a field doesn't move the whole struct

unsafe {

let mut_ref = Pin::as_mut(&mut heap_value);

Pin::get_unchecked_mut(mut_ref).self_ptr = ptr;

}

The get_unchecked_mut function works on a Pin<&mut T> instead of a Pin<Box<T>>, so we have to use Pin::as_mut for converting the value. Then we can set the self_ptr field using the &mut reference returned by get_unchecked_mut.

Now the only error left is the desired error on mem::replace. Remember, this operation tries to move the heap-allocated value to the stack, which would break the self-reference stored in the self_ptr field. By opting out of Unpin and using Pin<Box<T>>, we can prevent this operation at compile time and thus safely work with self-referential structs. As we saw, the compiler is not able to prove that the creation of the self-reference is safe (yet), so we need to use an unsafe block and verify the correctness ourselves.

Stack Pinning and Pin<&mut T>

In the previous section, we learned how to use Pin<Box<T>> to safely create a heap-allocated self-referential value. While this approach works fine and is relatively safe (apart from the unsafe construction), the required heap allocation comes with a performance cost. Since Rust strives to provide zero-cost abstractions whenever possible, the pinning API also allows to create Pin<&mut T> instances that point to stack-allocated values.

Unlike Pin<Box<T>> instances, which have ownership of the wrapped value, Pin<&mut T> instances only temporarily borrow the wrapped value. This makes things more complicated, as it requires the programmer to ensure additional guarantees themselves. Most importantly, a Pin<&mut T> must stay pinned for the whole lifetime of the referenced T, which can be difficult to verify for stack-based variables. To help with this, crates like pin-utils exist, but I still wouldn't recommend pinning to the stack unless you really know what you're doing.

For further reading, check out the documentation of the pin module and the Pin::new_unchecked method.

Pinning and Futures

As we already saw in this post, the Future::poll method uses pinning in the form of a Pin<&mut Self> parameter:

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output>

The reason that this method takes self: Pin<&mut Self> instead of the normal &mut self is that future instances created from async/await are often self-referential, as we saw above. By wrapping Self into Pin and letting the compiler opt-out of Unpin for self-referential futures generated from async/await, it is guaranteed that the futures are not moved in memory between poll calls. This ensures that all internal references are still valid.

It is worth noting that moving futures before the first poll call is fine. This is a result of the fact that futures are lazy and do nothing until they're polled for the first time. The start state of the generated state machines therefore only contains the function arguments but no internal references. In order to call poll, the caller must wrap the future into Pin first, which ensures that the future cannot be moved in memory anymore. Since stack pinning is more difficult to get right, I recommend to always use Box::pin combined with Pin::as_mut for this.

In case you're interested in understanding how to safely implement a future combinator function using stack pinning yourself, take a look at the relatively short source of the map combinator method of the futures crate and the section about projections and structural pinning of the pin documentation.

Executors and Wakers

Using async/await, it is possible to ergonomically work with futures in a completely asynchronous way. However, as we learned above, futures do nothing until they are polled. This means we have to call poll on them at some point, otherwise the asynchronous code is never executed.

With a single future, we can always wait for each future manually using a loop as described above. However, this approach is very inefficient and not practical for programs that create a large number of futures. The most common solution to this problem is to define a global executor that is responsible for polling all futures in the system until they are finished.

Executors

The purpose of an executor is to allow spawning futures as independent tasks, typically through some sort of spawn method. The executor is then responsible for polling all futures until they are completed. The big advantage of managing all futures in a central place is that the executor can switch to a different future whenever a future returns Poll::Pending. Thus, asynchronous operations are run in parallel and the CPU is kept busy.

Many executor implementations can also take advantage of systems with multiple CPU cores. They create a thread pool that is able to utilize all cores if there is enough work available and use techniques such as work stealing to balance the load between cores. There are also special executor implementations for embedded systems that optimize for low latency and memory overhead.

To avoid the overhead of polling futures repeatedly, executors typically take advantage of the waker API supported by Rust's futures.

Wakers

The idea behind the waker API is that a special Waker type is passed to each invocation of poll, wrapped in the Context type. This Waker type is created by the executor and can be used by the asynchronous task to signal its (partial) completion. As a result, the executor does not need to call poll on a future that previously returned Poll::Pending until it is notified by the corresponding waker.

This is best illustrated by a small example:

async fn write_file() {

async_write_file("foo.txt", "Hello").await;

}

This function asynchronously writes the string "Hello" to a foo.txt file. Since hard disk writes take some time, the first poll call on this future will likely return Poll::Pending. However, the hard disk driver will internally store the Waker passed to the poll call and use it to notify the executor when the file is written to disk. This way, the executor does not need to waste any time trying to poll the future again before it receives the waker notification.

We will see how the Waker type works in detail when we create our own executor with waker support in the implementation section of this post.

Cooperative Multitasking?

At the beginning of this post, we talked about preemptive and cooperative multitasking. While preemptive multitasking relies on the operating system to forcibly switch between running tasks, cooperative multitasking requires that the tasks voluntarily give up control of the CPU through a yield operation on a regular basis. The big advantage of the cooperative approach is that tasks can save their state themselves, which results in more efficient context switches and makes it possible to share the same call stack between tasks.

It might not be immediately apparent, but futures and async/await are an implementation of the cooperative multitasking pattern:

- Each future that is added to the executor is basically a cooperative task.

- Instead of using an explicit yield operation, futures give up control of the CPU core by returning

Poll::Pending(orPoll::Readyat the end).- There is nothing that forces futures to give up the CPU. If they want, they can never return from

poll, e.g., by spinning endlessly in a loop. - Since each future can block the execution of the other futures in the executor, we need to trust them to not be malicious.

- There is nothing that forces futures to give up the CPU. If they want, they can never return from

- Futures internally store all the state they need to continue execution on the next

pollcall. With async/await, the compiler automatically detects all variables that are needed and stores them inside the generated state machine.- Only the minimum state required for continuation is saved.

- Since the

pollmethod gives up the call stack when it returns, the same stack can be used for polling other futures.

We see that futures and async/await fit the cooperative multitasking pattern perfectly; they just use some different terminology. In the following, we will therefore use the terms "task" and "future" interchangeably.

Implementation

Now that we understand how cooperative multitasking based on futures and async/await works in Rust, it's time to add support for it to our kernel. Since the Future trait is part of the core library and async/await is a feature of the language itself, there is nothing special we need to do to use it in our #![no_std] kernel. The only requirement is that we use at least nightly 2020-03-25 of Rust because async/await was not no_std compatible before.

With a recent-enough nightly, we can start using async/await in our main.rs:

// in src/main.rs

async fn async_number() -> u32 {

42

}

async fn example_task() {

let number = async_number().await;

println!("async number: {}", number);

}

The async_number function is an async fn, so the compiler transforms it into a state machine that implements Future. Since the function only returns 42, the resulting future will directly return Poll::Ready(42) on the first poll call. Like async_number, the example_task function is also an async fn. It awaits the number returned by async_number and then prints it using the println macro.

To run the future returned by example_task, we need to call poll on it until it signals its completion by returning Poll::Ready. To do this, we need to create a simple executor type.

Task

Before we start the executor implementation, we create a new task module with a Task type:

// in src/lib.rs

pub mod task;

// in src/task/mod.rs

use core::{future::Future, pin::Pin};

use alloc::boxed::Box;

pub struct Task {

future: Pin<Box<dyn Future<Output = ()>>>,

}

The Task struct is a newtype wrapper around a pinned, heap-allocated, and dynamically dispatched future with the empty type () as output. Let's go through it in detail:

- We require that the future associated with a task returns

(). This means that tasks don't return any result, they are just executed for their side effects. For example, theexample_taskfunction we defined above has no return value, but it prints something to the screen as a side effect. - The

dynkeyword indicates that we store a trait object in theBox. This means that the methods on the future are dynamically dispatched, allowing different types of futures to be stored in theTasktype. This is important because eachasync fnhas its own type and we want to be able to create multiple different tasks. - As we learned in the section about pinning, the

Pin<Box>type ensures that a value cannot be moved in memory by placing it on the heap and preventing the creation of&mutreferences to it. This is important because futures generated by async/await might be self-referential, i.e., contain pointers to themselves that would be invalidated when the future is moved.

To allow the creation of new Task structs from futures, we create a new function:

// in src/task/mod.rs

impl Task {

pub fn new(future: impl Future<Output = ()> + 'static) -> Task {

Task {

future: Box::pin(future),

}

}

}

The function takes an arbitrary future with an output type of () and pins it in memory through the Box::pin function. Then it wraps the boxed future in the Task struct and returns it. The 'static lifetime is required here because the returned Task can live for an arbitrary time, so the future needs to be valid for that time too.

We also add a poll method to allow the executor to poll the stored future:

// in src/task/mod.rs

use core::task::{Context, Poll};

impl Task {

fn poll(&mut self, context: &mut Context) -> Poll<()> {

self.future.as_mut().poll(context)

}

}

Since the poll method of the Future trait expects to be called on a Pin<&mut T> type, we use the Pin::as_mut method to convert the self.future field of type Pin<Box<T>> first. Then we call poll on the converted self.future field and return the result. Since the Task::poll method should only be called by the executor that we'll create in a moment, we keep the function private to the task module.

Simple Executor

Since executors can be quite complex, we deliberately start by creating a very basic executor before implementing a more featureful executor later. For this, we first create a new task::simple_executor submodule:

// in src/task/mod.rs

pub mod simple_executor;

// in src/task/simple_executor.rs

use super::Task;

use alloc::collections::VecDeque;

pub struct SimpleExecutor {

task_queue: VecDeque<Task>,

}

impl SimpleExecutor {

pub fn new() -> SimpleExecutor {

SimpleExecutor {

task_queue: VecDeque::new(),

}

}

pub fn spawn(&mut self, task: Task) {

self.task_queue.push_back(task)

}

}

The struct contains a single task_queue field of type VecDeque, which is basically a vector that allows for push and pop operations on both ends. The idea behind using this type is that we insert new tasks through the spawn method at the end and pop the next task for execution from the front. This way, we get a simple FIFO queue ("first in, first out").

Dummy Waker

In order to call the poll method, we need to create a Context type, which wraps a Waker type. To start simple, we will first create a dummy waker that does nothing. For this, we create a RawWaker instance, which defines the implementation of the different Waker methods, and then use the Waker::from_raw function to turn it into a Waker:

// in src/task/simple_executor.rs

use core::task::{Waker, RawWaker};

fn dummy_raw_waker() -> RawWaker {

todo!();

}

fn dummy_waker() -> Waker {

unsafe { Waker::from_raw(dummy_raw_waker()) }

}

The from_raw function is unsafe because undefined behavior can occur if the programmer does not uphold the documented requirements of RawWaker. Before we look at the implementation of the dummy_raw_waker function, we first try to understand how the RawWaker type works.

RawWaker

The RawWaker type requires the programmer to explicitly define a virtual method table (vtable) that specifies the functions that should be called when the RawWaker is cloned, woken, or dropped. The layout of this vtable is defined by the RawWakerVTable type. Each function receives a *const () argument, which is a type-erased pointer to some value. The reason for using a *const () pointer instead of a proper reference is that the RawWaker type should be non-generic but still support arbitrary types. The pointer is provided by putting it into the data argument of RawWaker::new, which just initializes a RawWaker. The Waker then uses this RawWaker to call the vtable functions with data.

Typically, the RawWaker is created for some heap-allocated struct that is wrapped into the Box or Arc type. For such types, methods like Box::into_raw can be used to convert the Box<T> to a *const T pointer. This pointer can then be cast to an anonymous *const () pointer and passed to RawWaker::new. Since each vtable function receives the same *const () as an argument, the functions can safely cast the pointer back to a Box<T> or a &T to operate on it. As you can imagine, this process is highly dangerous and can easily lead to undefined behavior on mistakes. For this reason, manually creating a RawWaker is not recommended unless necessary.

A Dummy RawWaker

While manually creating a RawWaker is not recommended, there is currently no other way to create a dummy Waker that does nothing. Fortunately, the fact that we want to do nothing makes it relatively safe to implement the dummy_raw_waker function:

// in src/task/simple_executor.rs

use core::task::RawWakerVTable;

fn dummy_raw_waker() -> RawWaker {

fn no_op(_: *const ()) {}

fn clone(_: *const ()) -> RawWaker {

dummy_raw_waker()

}

let vtable = &RawWakerVTable::new(clone, no_op, no_op, no_op);

RawWaker::new(0 as *const (), vtable)

}

First, we define two inner functions named no_op and clone. The no_op function takes a *const () pointer and does nothing. The clone function also takes a *const () pointer and returns a new RawWaker by calling dummy_raw_waker again. We use these two functions to create a minimal RawWakerVTable: The clone function is used for the cloning operations, and the no_op function is used for all other operations. Since the RawWaker does nothing, it does not matter that we return a new RawWaker from clone instead of cloning it.

After creating the vtable, we use the RawWaker::new function to create the RawWaker. The passed *const () does not matter since none of the vtable functions use it. For this reason, we simply pass a null pointer.

A run Method

Now we have a way to create a Waker instance, we can use it to implement a run method on our executor. The most simple run method is to repeatedly poll all queued tasks in a loop until all are done. This is not very efficient since it does not utilize the notifications of the Waker type, but it is an easy way to get things running:

// in src/task/simple_executor.rs

use core::task::{Context, Poll};

impl SimpleExecutor {

pub fn run(&mut self) {

while let Some(mut task) = self.task_queue.pop_front() {

let waker = dummy_waker();

let mut context = Context::from_waker(&waker);

match task.poll(&mut context) {

Poll::Ready(()) => {} // task done

Poll::Pending => self.task_queue.push_back(task),

}

}

}

}

The function uses a while let loop to handle all tasks in the task_queue. For each task, it first creates a Context type by wrapping a Waker instance returned by our dummy_waker function. Then it invokes the Task::poll method with this context. If the poll method returns Poll::Ready, the task is finished and we can continue with the next task. If the task is still Poll::Pending, we add it to the back of the queue again so that it will be polled again in a subsequent loop iteration.

Trying It

With our SimpleExecutor type, we can now try running the task returned by the example_task function in our main.rs:

// in src/main.rs

use blog_os::task::{Task, simple_executor::SimpleExecutor};

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// […] initialization routines, including `init_heap`

let mut executor = SimpleExecutor::new();

executor.spawn(Task::new(example_task()));

executor.run();

// […] test_main, "it did not crash" message, hlt_loop

}

// Below is the example_task function again so that you don't have to scroll up

async fn async_number() -> u32 {

42

}

async fn example_task() {

let number = async_number().await;

println!("async number: {}", number);

}

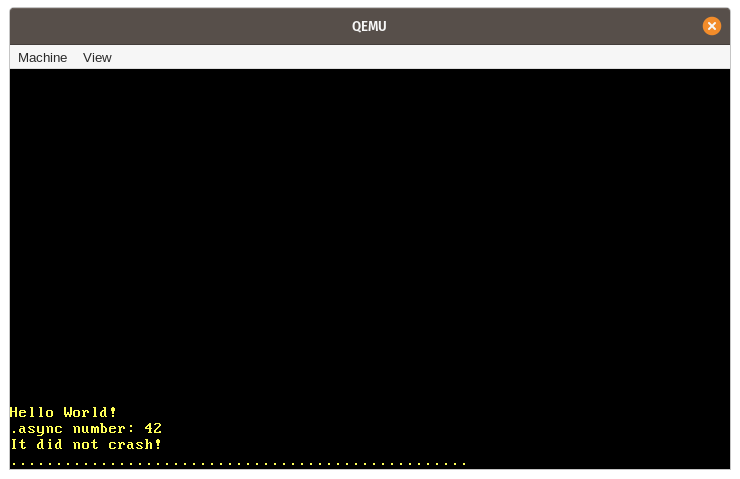

When we run it, we see that the expected "async number: 42" message is printed to the screen:

Let's summarize the various steps that happen in this example:

- First, a new instance of our

SimpleExecutortype is created with an emptytask_queue. - Next, we call the asynchronous

example_taskfunction, which returns a future. We wrap this future in theTasktype, which moves it to the heap and pins it, and then add the task to thetask_queueof the executor through thespawnmethod. - We then call the

runmethod to start the execution of the single task in the queue. This involves:- Popping the task from the front of the

task_queue. - Creating a

RawWakerfor the task, converting it to aWakerinstance, and then creating aContextinstance from it. - Calling the

pollmethod on the future of the task, using theContextwe just created. - Since the

example_taskdoes not wait for anything, it can directly run till its end on the firstpollcall. This is where the "async number: 42" line is printed. - Since the

example_taskdirectly returnsPoll::Ready, it is not added back to the task queue.

- Popping the task from the front of the

- The

runmethod returns after thetask_queuebecomes empty. The execution of ourkernel_mainfunction continues and the "It did not crash!" message is printed.

Async Keyboard Input

Our simple executor does not utilize the Waker notifications and simply loops over all tasks until they are done. This wasn't a problem for our example since our example_task can directly run to finish on the first poll call. To see the performance advantages of a proper Waker implementation, we first need to create a task that is truly asynchronous, i.e., a task that will probably return Poll::Pending on the first poll call.

We already have some kind of asynchronicity in our system that we can use for this: hardware interrupts. As we learned in the Interrupts post, hardware interrupts can occur at arbitrary points in time, determined by some external device. For example, a hardware timer sends an interrupt to the CPU after some predefined time has elapsed. When the CPU receives an interrupt, it immediately transfers control to the corresponding handler function defined in the interrupt descriptor table (IDT).

In the following, we will create an asynchronous task based on the keyboard interrupt. The keyboard interrupt is a good candidate for this because it is both non-deterministic and latency-critical. Non-deterministic means that there is no way to predict when the next key press will occur because it is entirely dependent on the user. Latency-critical means that we want to handle the keyboard input in a timely manner, otherwise the user will feel a lag. To support such a task in an efficient way, it will be essential that the executor has proper support for Waker notifications.

Scancode Queue

Currently, we handle the keyboard input directly in the interrupt handler. This is not a good idea for the long term because interrupt handlers should stay as short as possible as they might interrupt important work. Instead, interrupt handlers should only perform the minimal amount of work necessary (e.g., reading the keyboard scancode) and leave the rest of the work (e.g., interpreting the scancode) to a background task.

A common pattern for delegating work to a background task is to create some sort of queue. The interrupt handler pushes units of work to the queue, and the background task handles the work in the queue. Applied to our keyboard interrupt, this means that the interrupt handler only reads the scancode from the keyboard, pushes it to the queue, and then returns. The keyboard task sits on the other end of the queue and interprets and handles each scancode that is pushed to it:

A simple implementation of that queue could be a mutex-protected VecDeque. However, using mutexes in interrupt handlers is not a good idea since it can easily lead to deadlocks. For example, when the user presses a key while the keyboard task has locked the queue, the interrupt handler tries to acquire the lock again and hangs indefinitely. Another problem with this approach is that VecDeque automatically increases its capacity by performing a new heap allocation when it becomes full. This can lead to deadlocks again because our allocator also uses a mutex internally. Further problems are that heap allocations can fail or take a considerable amount of time when the heap is fragmented.

To prevent these problems, we need a queue implementation that does not require mutexes or allocations for its push operation. Such queues can be implemented by using lock-free atomic operations for pushing and popping elements. This way, it is possible to create push and pop operations that only require a &self reference and are thus usable without a mutex. To avoid allocations on push, the queue can be backed by a pre-allocated fixed-size buffer. While this makes the queue bounded (i.e., it has a maximum length), it is often possible to define reasonable upper bounds for the queue length in practice, so that this isn't a big problem.

The crossbeam Crate

Implementing such a queue in a correct and efficient way is very difficult, so I recommend sticking to existing, well-tested implementations. One popular Rust project that implements various mutex-free types for concurrent programming is crossbeam. It provides a type named ArrayQueue that is exactly what we need in this case. And we're lucky: the type is fully compatible with no_std crates with allocation support.

To use the type, we need to add a dependency on the crossbeam-queue crate:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies.crossbeam-queue]

version = "0.3.11"

default-features = false

features = ["alloc"]

By default, the crate depends on the standard library. To make it no_std compatible, we need to disable its default features and instead enable the alloc feature. (Note that we could also add a dependency on the main crossbeam crate, which re-exports the crossbeam-queue crate, but this would result in a larger number of dependencies and longer compile times.)

Queue Implementation

Using the ArrayQueue type, we can now create a global scancode queue in a new task::keyboard module:

// in src/task/mod.rs

pub mod keyboard;

// in src/task/keyboard.rs

use conquer_once::spin::OnceCell;

use crossbeam_queue::ArrayQueue;

static SCANCODE_QUEUE: OnceCell<ArrayQueue<u8>> = OnceCell::uninit();

Since ArrayQueue::new performs a heap allocation, which is not possible at compile time (yet), we can't initialize the static variable directly. Instead, we use the OnceCell type of the conquer_once crate, which makes it possible to perform a safe one-time initialization of static values. To include the crate, we need to add it as a dependency in our Cargo.toml:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies.conquer-once]

version = "0.2.0"

default-features = false

Instead of the OnceCell primitive, we could also use the lazy_static macro here. However, the OnceCell type has the advantage that we can ensure that the initialization does not happen in the interrupt handler, thus preventing the interrupt handler from performing a heap allocation.

Filling the Queue

To fill the scancode queue, we create a new add_scancode function that we will call from the interrupt handler:

// in src/task/keyboard.rs

use crate::println;

/// Called by the keyboard interrupt handler

///

/// Must not block or allocate.

pub(crate) fn add_scancode(scancode: u8) {

if let Ok(queue) = SCANCODE_QUEUE.try_get() {

if let Err(_) = queue.push(scancode) {

println!("WARNING: scancode queue full; dropping keyboard input");

}

} else {

println!("WARNING: scancode queue uninitialized");

}

}

We use OnceCell::try_get to get a reference to the initialized queue. If the queue is not initialized yet, we ignore the keyboard scancode and print a warning. It's important that we don't try to initialize the queue in this function because it will be called by the interrupt handler, which should not perform heap allocations. Since this function should not be callable from our main.rs, we use the pub(crate) visibility to make it only available to our lib.rs.

The fact that the ArrayQueue::push method requires only a &self reference makes it very simple to call the method on the static queue. The ArrayQueue type performs all the necessary synchronization itself, so we don't need a mutex wrapper here. In case the queue is full, we print a warning too.

To call the add_scancode function on keyboard interrupts, we update our keyboard_interrupt_handler function in the interrupts module:

// in src/interrupts.rs

extern "x86-interrupt" fn keyboard_interrupt_handler(

_stack_frame: InterruptStackFrame

) {

use x86_64::instructions::port::Port;

let mut port = Port::new(0x60);

let scancode: u8 = unsafe { port.read() };

crate::task::keyboard::add_scancode(scancode); // new

unsafe {

PICS.lock()

.notify_end_of_interrupt(InterruptIndex::Keyboard.as_u8());

}

}

We removed all the keyboard handling code from this function and instead added a call to the add_scancode function. The rest of the function stays the same as before.

As expected, keypresses are no longer printed to the screen when we run our project using cargo run now. Instead, we see the warning that the scancode queue is uninitialized for every keystroke.

Scancode Stream

To initialize the SCANCODE_QUEUE and read the scancodes from the queue in an asynchronous way, we create a new ScancodeStream type:

// in src/task/keyboard.rs

pub struct ScancodeStream {

_private: (),

}

impl ScancodeStream {

pub fn new() -> Self {

SCANCODE_QUEUE.try_init_once(|| ArrayQueue::new(100))

.expect("ScancodeStream::new should only be called once");

ScancodeStream { _private: () }

}

}

The purpose of the _private field is to prevent construction of the struct from outside of the module. This makes the new function the only way to construct the type. In the function, we first try to initialize the SCANCODE_QUEUE static. We panic if it is already initialized to ensure that only a single ScancodeStream instance can be created.

To make the scancodes available to asynchronous tasks, the next step is to implement a poll-like method that tries to pop the next scancode off the queue. While this sounds like we should implement the Future trait for our type, this does not quite fit here. The problem is that the Future trait only abstracts over a single asynchronous value and expects that the poll method is not called again after it returns Poll::Ready. Our scancode queue, however, contains multiple asynchronous values, so it is okay to keep polling it.

The Stream Trait

Since types that yield multiple asynchronous values are common, the futures crate provides a useful abstraction for such types: the Stream trait. The trait is defined like this:

pub trait Stream {

type Item;

fn poll_next(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context)

-> Poll<Option<Self::Item>>;

}

This definition is quite similar to the Future trait, with the following differences:

- The associated type is named

Iteminstead ofOutput. - Instead of a

pollmethod that returnsPoll<Self::Item>, theStreamtrait defines apoll_nextmethod that returns aPoll<Option<Self::Item>>(note the additionalOption).

There is also a semantic difference: The poll_next can be called repeatedly, until it returns Poll::Ready(None) to signal that the stream is finished. In this regard, the method is similar to the Iterator::next method, which also returns None after the last value.

Implementing Stream

Let's implement the Stream trait for our ScancodeStream to provide the values of the SCANCODE_QUEUE in an asynchronous way. For this, we first need to add a dependency on the futures-util crate, which contains the Stream type:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies.futures-util]

version = "0.3.4"

default-features = false

features = ["alloc"]

We disable the default features to make the crate no_std compatible and enable the alloc feature to make its allocation-based types available (we will need this later). (Note that we could also add a dependency on the main futures crate, which re-exports the futures-util crate, but this would result in a larger number of dependencies and longer compile times.)

Now we can import and implement the Stream trait:

// in src/task/keyboard.rs

use core::{pin::Pin, task::{Poll, Context}};

use futures_util::stream::Stream;

impl Stream for ScancodeStream {

type Item = u8;

fn poll_next(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Option<u8>> {

let queue = SCANCODE_QUEUE.try_get().expect("not initialized");

match queue.pop() {

Some(scancode) => Poll::Ready(Some(scancode)),

None => Poll::Pending,

}

}

}

We first use the OnceCell::try_get method to get a reference to the initialized scancode queue. This should never fail since we initialize the queue in the new function, so we can safely use the expect method to panic if it's not initialized. Next, we use the ArrayQueue::pop method to try to get the next element from the queue. If it succeeds, we return the scancode wrapped in Poll::Ready(Some(…)). If it fails, it means that the queue is empty. In that case, we return Poll::Pending.

Waker Support

Like the Futures::poll method, the Stream::poll_next method requires the asynchronous task to notify the executor when it becomes ready after Poll::Pending is returned. This way, the executor does not need to poll the same task again until it is notified, which greatly reduces the performance overhead of waiting tasks.

To send this notification, the task should extract the Waker from the passed Context reference and store it somewhere. When the task becomes ready, it should invoke the wake method on the stored Waker to notify the executor that the task should be polled again.

AtomicWaker

To implement the Waker notification for our ScancodeStream, we need a place where we can store the Waker between poll calls. We can't store it as a field in the ScancodeStream itself because it needs to be accessible from the add_scancode function. The solution to this is to use a static variable of the AtomicWaker type provided by the futures-util crate. Like the ArrayQueue type, this type is based on atomic instructions and can be safely stored in a static and modified concurrently.

Let's use the AtomicWaker type to define a static WAKER:

// in src/task/keyboard.rs

use futures_util::task::AtomicWaker;

static WAKER: AtomicWaker = AtomicWaker::new();

The idea is that the poll_next implementation stores the current waker in this static, and the add_scancode function calls the wake function on it when a new scancode is added to the queue.

Storing a Waker

The contract defined by poll/poll_next requires the task to register a wakeup for the passed Waker when it returns Poll::Pending. Let's modify our poll_next implementation to satisfy this requirement:

// in src/task/keyboard.rs

impl Stream for ScancodeStream {

type Item = u8;

fn poll_next(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Option<u8>> {

let queue = SCANCODE_QUEUE

.try_get()

.expect("scancode queue not initialized");

// fast path

if let Some(scancode) = queue.pop() {

return Poll::Ready(Some(scancode));

}

WAKER.register(&cx.waker());

match queue.pop() {

Some(scancode) => {

WAKER.take();

Poll::Ready(Some(scancode))

}

None => Poll::Pending,

}

}

}

Like before, we first use the OnceCell::try_get function to get a reference to the initialized scancode queue. We then optimistically try to pop from the queue and return Poll::Ready when it succeeds. This way, we can avoid the performance overhead of registering a waker when the queue is not empty.

If the first call to queue.pop() does not succeed, the queue is potentially empty. Only potentially because the interrupt handler might have filled the queue asynchronously immediately after the check. Since this race condition can occur again for the next check, we need to register the Waker in the WAKER static before the second check. This way, a wakeup might happen before we return Poll::Pending, but it is guaranteed that we get a wakeup for any scancodes pushed after the check.