44 KiB

+++ title = "UEFI Booting" path = "booting/uefi" date = 0000-01-01 template = "edition-3/page.html"

[extra] hide_next_prev = true icon = '''

''' +++This post is an addendum to our main Booting post. It explains how to create a basic UEFI application from scratch that can be directly booted on modern x86_64 systems. This includes creating a minimal application suitable for the UEFI environment, turning it into a bootable disk image, and interacting with the hardware through the UEFI system tables and the uefi crate.

This blog is openly developed on GitHub. If you have any problems or questions, please open an issue there. You can also leave comments at the bottom.

Minimal UEFI App

We start by creating a new cargo project with a Cargo.toml and a src/main.rs:

# in Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "uefi_app"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["Your Name <your-email@example.com>"]

edition = "2018"

[dependencies]

This uefi_app project is independent of the OS kernel created in the Booting, so we use a separate directory.

In the src/main.rs, we create a minimal no_std executable as shown in the Minimal Kernel post:

// in src/main.rs

#![no_std]

#![no_main]

use core::panic::PanicInfo;

#[panic_handler]

fn panic(_info: &PanicInfo) -> ! {

loop {}

}

The #![no_std] attribute disables the linking of the Rust standard library, which is not available on bare metal. The #![no_main] attribute, we disable the normal entry point function that based on the C runtime. The #[panic_handler] attribute specifies which function should be called when a panic occurs.

Next, we create an entry point function named efi_main:

// in src/main.rs

#![feature(abi_efiapi)]

use core::ffi::c_void;

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "efiapi" fn efi_main(

image: *mut c_void,

system_table: *const c_void,

) -> usize {

loop {}

}

This function signature is standardized by the UEFI specification, which is available in PDF form on uefi.org. You can find the signature of the entry point function in section 4.1. Since UEFI also defines a specific calling convention (in section 2.3), we set the efiapi calling convention for our function. Since support for this calling function is still unstable in Rust, we need to add #![feature(abi_efiapi)] at the very top of our file.

The function takes two arguments: an image handle and a system table. The image handle is a firmware-allocated handle that identifies the UEFI image. The system table contains some input and output handles and provides access to various functions provided by the UEFI firmware. The function returns an EFI_STATUS integer to signal whether the function was successful. It is normally only returned by UEFI apps that are not bootloaders, e.g. UEFI drivers or apps that are launched manually from the UEFI shell. Bootloaders typically pass control to a OS kernel and never return.

UEFI Target

For our minimal kernel, we needed to create a custom target because none of the officially supported targets was suitable. For our UEFI application we are more lucky: Rust has built-in support for a x86_64-unknown-uefi target, which we can use without problems.

If you're curious, you can query the JSON specification of the target with the following command:

rustc +nightly --print target-spec-json -Z unstable-options --target x86_64-unknown-uefi

This outputs looks something like the following:

{

"abi-return-struct-as-int": true,

"allows-weak-linkage": false,

"arch": "x86_64",

"code-model": "large",

"cpu": "x86-64",

"data-layout": "e-m:w-p270:32:32-p271:32:32-p272:64:64-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

"disable-redzone": true,

"emit-debug-gdb-scripts": false,

"exe-suffix": ".efi",

"executables": true,

"features": "-mmx,-sse,+soft-float",

"is-builtin": true,

"is-like-msvc": true,

"is-like-windows": true,

"linker": "rust-lld",

"linker-flavor": "lld-link",

"lld-flavor": "link",

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-windows",

"max-atomic-width": 64,

"os": "uefi",

"panic-strategy": "abort",

"pre-link-args": {

"lld-link": [

"/NOLOGO",

"/NXCOMPAT",

"/entry:efi_main",

"/subsystem:efi_application"

],

"msvc": [

"/NOLOGO",

"/NXCOMPAT",

"/entry:efi_main",

"/subsystem:efi_application"

]

},

"singlethread": true,

"split-debuginfo": "packed",

"stack-probes": {

"kind": "call"

},

"target-pointer-width": "64"

}

From the output we can derive multiple properties of the target:

- The

exe-suffixis.efi, which means that all executables compiled for this target have the suffix.efi. - As for our kernel target, both the redzone and SSE are disabled.

- The

is-like-windowsis an indicator that the target uses the conventions of Windows world, e.g. PE instead of ELF executables. - The LLD linker is used, which means that we don't have to install any additional linker even when compiling on non-Windows systems.

- Like for all (most?) bare-metal targets, the

panic-strategyis set toabortto disable unwinding. - Various linker arguments are specified. For example, the

/entryargument sets the name of the entry point function. This is the reason that we named our entry point functionefi_mainand applied the#[no_mangle]attribute above.

If you're interested in understanding all these fields, check out the docs for Rust's internal Target and TargetOptions types. These are the types that the above JSON is converted to.

Building

Even though the x86_64-unknown-uefi target is built-in, there are no precompiled versions of the core library available for it. This means that we need to use cargo's build-std feature as described in the Minimal Kernel post.

A nightly Rust compiler is required for building, so we need to set up a rustup override for the directory. We can do this either by running a [rustup ovrride command] or by adding a rust-toolchain file.

The full build command looks like this:

cargo build --target x86_64-unknown-uefi -Z build-std=core \

-Z build-std-features=compiler-builtins-mem

This results in a uefi_app.efi file in our x86_64-unknown-uefi/debug folder. Congratulations! We just created our own minimal UEFI app.

Bootable Disk Image

To make our minimal UEFI app bootable, we need to create a new GPT disk image with a EFI system partition. On that partition, we need to put our .efi file under efi\boot\bootx64.efi. Then the UEFI firmware should automatically detect and load it when we boot from the corresponding disk. See the section about the UEFI boot process in the Booting post for more details.

To create this disk image, we create a new disk_image executable:

> cargo new --bin disk_image

This creates a new cargo project in a disk_image subdirectory. To share the target folder and Cargo.lock file with our uefi_app project, we set up a cargo workspace:

# in Cargo.toml

[workspace]

members = ["disk_image"]

FAT Filesystem

The first step to create an EFI system partition is to create a new partition image formatted with the FAT file system. The reason for using FAT is that this is the only file system that the UEFI standard requires. In practice, most UEFI firmware implementations also support the NTFS filesystem, but we can't rely on that since this is not required by the standard.

To create a new FAT file system, we use the fatfs crate:

# in disk_image/Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

fatfs = "0.3.5"

We leave the main function unchanged for now and instead create a create_fat_filesystem function next to it:

// in disk_image/src/main.rs

use std::{fs, io, path::Path};

fn create_fat_filesystem(fat_path: &Path, efi_file: &Path) {

// retrieve size of `.efi` file and round it up

let efi_size = fs::metadata(&efi_file).unwrap().len();

let mb = 1024 * 1024; // size of a megabyte

// round it to next megabyte

let efi_size_rounded = ((efi_size - 1) / mb + 1) * mb;

// create new filesystem image file at the given path and set its length

let fat_file = fs::OpenOptions::new()

.read(true)

.write(true)

.create(true)

.truncate(true)

.open(&fat_path)

.unwrap();

fat_file.set_len(efi_size_rounded).unwrap();

// create new FAT file system and open it

let format_options = fatfs::FormatVolumeOptions::new();

fatfs::format_volume(&fat_file, format_options).unwrap();

let filesystem = fatfs::FileSystem::new(&fat_file, fatfs::FsOptions::new()).unwrap();

// copy EFI file to FAT filesystem

let root_dir = filesystem.root_dir();

root_dir.create_dir("efi").unwrap();

root_dir.create_dir("efi/boot").unwrap();

let mut bootx64 = root_dir.create_file("efi/boot/bootx64.efi").unwrap();

bootx64.truncate().unwrap();

io::copy(&mut fs::File::open(&efi_file).unwrap(), &mut bootx64).unwrap();

}

We first use fs::metadata to query the size of our .efi file and then round it up to the next megabyte. We then use this rounded size to create a new FAT filesystem image file. I'm not sure if the rounding is really necessary, but I had some problems with the fatfs crate when trying to use the unaligned size.

After creating the file that should hold the FAT filesystem image, we use the format_volume function of fatfs to create the new FAT filesystem. After creating it, we use the FileSystem::new function to open it. The last step is to create the efi/boot directory and the bootx64.efi file on the filesystem. To write our .efi file to the filesystem image, we use the io::copy function of the Rust standard library.

Note that we're not doing any error handling here to keep the code short. This is not that problematic because the disk_image crate is only part of our build process, but you still might to use at least expect instead of unwrap() or an error handling crate such as anyhow.

GPT Disk Image

To make the FAT filesystem that we just created bootable, we need to place it as an EFI system partition on a GPT-formatted disk. To create the GPT disk image, we use the gpt crate:

# in disk_image/Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

gpt = "2.0.0"

Like for the FAT image, we create a separate function to create the GPT disk image:

// in disk_image/src/main.rs

use std::{convert::TryFrom, fs::File, io::Seek};

fn create_gpt_disk(disk_path: &Path, fat_image: &Path) {

// create new file

let mut disk = fs::OpenOptions::new()

.create(true)

.truncate(true)

.read(true)

.write(true)

.open(&disk_path)

.unwrap();

// set file size

let partition_size: u64 = fs::metadata(&fat_image).unwrap().len();

let disk_size = partition_size + 1024 * 64; // for GPT headers

disk.set_len(disk_size).unwrap();

// create a protective MBR at LBA0 so that disk is not considered

// unformatted on BIOS systems

let mbr = gpt::mbr::ProtectiveMBR::with_lb_size(

u32::try_from((disk_size / 512) - 1).unwrap_or(0xFF_FF_FF_FF),

);

mbr.overwrite_lba0(&mut disk).unwrap();

// create new GPT structure

let block_size = gpt::disk::LogicalBlockSize::Lb512;

let mut gpt = gpt::GptConfig::new()

.writable(true)

.initialized(false)

.logical_block_size(block_size)

.create_from_device(Box::new(&mut disk), None)

.unwrap();

gpt.update_partitions(Default::default()).unwrap();

// add new EFI system partition and get its byte offset in the file

let partition_id = gpt

.add_partition("boot", partition_size, gpt::partition_types::EFI, 0)

.unwrap();

let partition = gpt.partitions().get(&partition_id).unwrap();

let start_offset = partition.bytes_start(block_size).unwrap();

// close the GPT structure and write out changes

gpt.write().unwrap();

// place the FAT filesystem in the newly created partition

disk.seek(io::SeekFrom::Start(start_offset)).unwrap();

io::copy(&mut File::open(&fat_image).unwrap(), &mut disk).unwrap();

}

First, we create a new disk image file at the given disk_path. We set its size to the size of the FAT partition plus some extra amount to account for the GPT structure itself.

To ensure that the disk image is not detected as an unformatted disk on older systems and accidentally overwritten, we create a so-called protective MBR. The idea is to create a normal master boot record structure on the disk that specifies a single partition that spans the whole disk. This way, older systems that don't know the GPT format see a disk formatted with an unknown parititon type instead of an unformatted disk.

Next, we create the actual GPT structure through the GptConfig type and its create_from_device method. The result is a GptDisk type that writes to our disk file. Since we want to start with an empty partition table, we use the update_partitions method to reset the partition table. This isn't strictly necessary since we create a completely new GPT disk, but it's better to be safe.

After resetting the new partition table, we create a new partition named boot in the partition table. This operation only looks for a free region on the disk and stores the offset and size of that region in the table, together with the partition name and type (an EFI system partition in this case). It does not write any bytes to the partition itself. To do that later, we keep track of the start_offset of the partition.

At this point, we are done with the GPT structure. To write it out to our disk file, we use the GptDisk::write function.

The final step is to write our FAT filesystem image to the newly created partition. For that we use the Seek::seek function to move the file cursor to the start_offset of the parititon. We then use the io::copy function to copy all the bytes from our FAT image file to the disk partition.

Putting it Together

We now have functions to create the FAT filesystem and GPT disk image. We just need to put them together in our main function:

// in disk_image/src/main.rs

use std::path::PathBuf;

fn main() {

// take efi file path as command line argument

let mut args = std::env::args();

let _exe_name = args.next().unwrap();

let efi_path = PathBuf::from(args.next()

.expect("path to `.efi` files must be given as argument"));

let fat_path = efi_path.with_extension("fat");

let disk_path = fat_path.with_extension("img");

create_fat_filesystem(&fat_path, &efi_path);

create_gpt_disk(&disk_path, &fat_path);

}

To be flexible, we take the path to the .efi file as command line argument. For retrieving the arguments we use the env::args function. The first argument is always set to the path of the executable itself by the operating system, even if the executable is invoked without arguments. We don't need it, so we prefix the variable name with an underscore to silence the "unused variable" warning.

Note that this is a very rudimentary way of doing argument parsing. There are a lot of crates out there that provide nice abstractions for this, for example clap, structopt, or argh. It is strongly recommend to use such a crate instead of writing your own argument parsing.

From the efi_path given as argument, we construct the fat_path and disk_path. By changing only the file extension using Path::with_extension, we place the FAT and GPT image file next to our .efi file. The final step is to invoke our create_fat_filesystem and create_gpt_disk functions with the corresponding paths as argument.

Now we can run our disk_image executable to create the bootable disk image from our uefi_app:

cargo run --package disk_image -- target/x86_64-unknown-uefi/debug/uefi_app.efi

Note the additional -- argument. The cargo run uses this special argument to separate cargo run arguments from the arguments that should be passed to the compiled executable. The path of course depends on your working directory, i.e. whether you run it from the project root or from the disk_image subdirectory. It also depends on whether you compiled the uefi_app in debug or --release mode.

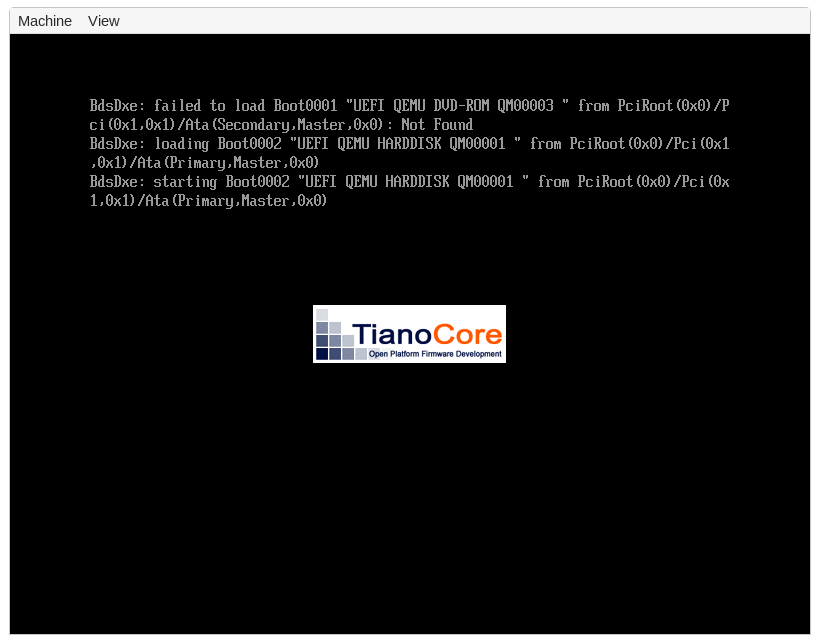

The result of this command is a .fat and a .img file next to the given .efi executable. These files can be launched in QEMU and on real hardware as described in the main Booting post. The result should look something like this:

We don't see any output from our uefi_app on the screen yet since we only loop {} in our efi_main. Instead, we see some output from the UEFI firmware itself that was created before our application was started.

Let's try to improve this by printing something to the screen from our uefi_app as well.

The uefi Crate

In order to print something to the screen, we need to call some functions provided by the UEFI firmware. These functions can be invoked through the system_table argument passed to our efi_main function. This table provides function pointers for all kinds of functionality, including access to the screen, disk, or network.

Since the system table has a standardized format that is identical on all systems, it makes sense to create an abstraction for it. This is what the uefi crate does. It provides a SystemTable type that abstracts the UEFI system table functions as normal Rust methods. It is not complete, but the most important functions are all available.

To use the crate, we first add it as a dependency in our root Cargo.toml (not in disk_image/Cargo.toml):

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

uefi = "0.8.0"

Now we can change the types of the image and system_table arguments in our efi_main declaration:

// in src/main.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "efiapi" fn efi_main(

image: uefi::Handle,

system_table: uefi::table::SystemTable<uefi::table::Boot>,

) -> uefi::Status {

loop {}

}

Instead of using raw pointers and an anonymous usize return type, we now use the Handle, SystemTable, and Status abstraction types provided by the uefi crate. This way, we can use the higher-level API provided by the crate instead of carefully calculating pointer offsets to access the system table manually.

While the above function signature works, it is very fragile because the Rust compiler is not able to typecheck the function signature of entry point functions. Thus, we could accidentally use the wrong signature (e.g. after updating the uefi crate), which would cause undefined behavior. To prevent this, the uefi crate provides an entry macro to enforce the correct signature. To use it, we change our entry point function in the following way:

// in src/main.rs

use uefi::prelude::entry;

#[entry]

fn efi_main(

image: uefi::Handle,

system_table: uefi::table::SystemTable<uefi::table::Boot>,

) -> uefi::Status {

loop {}

}

The macro already inserts the #[no_mangle] attribute and the pub extern "efiapi" modifiers for us, so we no longer need them. We will now get a compile error if the function signature is not correct (try it if you like).

Printing to Screen

The UEFI standard supports multiple interfaces for printing to the screen. The most simple one is the Simple Text Output protocol, which provides a console-like output interface. It is described in section 11.4 of the UEFI specification (PDF). We can use it through the SystemTable::stdout method provided by theThe uefi crate supportsuefi crate:

// in src/main.rs

use core::fmt::Write;

#[entry]

fn efi_main(

image: uefi::Handle,

system_table: uefi::table::SystemTable<uefi::table::Boot>,

) -> uefi::Status {

let stdout = system_table.stdout();

stdout.clear().unwrap().unwrap();

writeln!(stdout, "Hello World!").unwrap();

loop {}

}

We first use the SystemTable::stdout method to get an Output reference. Through this reference, we can then clear the screen and write a "Hello World!" message through Rust's writeln macro. In order to be able to use the macro, we need to import the fmt::Write trait. Since this is only prototype code, we use the Result::unwrap method to panic on errors. For the clear call, we additionally call the Completion::unwrap method to ensure that the UEFI firmware did not throw any warnings.

After recompiling and creating a new disk image, we can now see out "Hello World!" on the screen:

> cargo build --target x86_64-unknown-uefi -Z build-std=core \

-Z build-std-features=compiler-builtins-mem

> cargo run --package disk_image -- target/x86_64-unknown-uefi/debug/uefi_app.efi

> qemu-system-x86_64 -drive format=raw,file=target/x86_64-unknown-uefi/debug/uefi_app.fat \

-bios # [...] TODO

The Output type also allows to use different colors through its set_color method and some other customization options.

All of these functions are directly provided by the UEFI firmware, the uefi crate just provides some abstractions for this. By looking at the source code of the uefi crate, we see that the SystemTable is just a pointer to a SystemTableImpl struct, which is created by the UEFI firmware in a standardized format (see section 4.3 of the UEFI specification (PDF)). It has a stdout field, which is a pointer to an Output table fillThe uefi crate supportsd with function pointers. The methods of the Output type are just small wrappers around these function pointers, so all of the functionality is implemented directly in the UEFI firmware.

Boot Services

If we take a closer look at the documentation of the SystemTable type, we see that it has a generic View parameter. The documentation provides a good explanation why this parameter is needed:

[...] Not all UEFI services will remain accessible forever. Some services, called "boot services", may only be called during a bootstrap stage where the UEFI firmware still has control of the hardware, and will become unavailable once the firmware hands over control of the hardware to an operating system loader. Others, called "runtime services", may still be used after that point [...]

We handle this state transition by providing two different views of the UEFI system table, the "Boot" view and the "Runtime" view.

The distinction between "boot" and "runtime" services is defined directly by the UEFI standard ( in section 6), the uefi crate just provides an abstraction for this. The distinction is necessary because the UEFI firmware provides such a wide range of functionality, for example a memory allocator or access to network devices. These functions can easily conflict with operating system functionality, so they are only available before an operating system is loaded. To hand over hardware control from the UEFI firmware to an operating system, the UEFI standard provides an ExitBootServices function. The uefi crate abstracts this function as an SystemTable::exit_boot_services method.

Interesting UEFI Protocols

The UEFI firmware supports many different hardware functions through so-called protocols. Most of them are not used by traditional operating systems, which instead implement their own drivers and access the different hardware devices directly. There are multiple reasons for this. For one, many protocols are no longer available after exiting boot services, so using the protocols is only possible as long as UEFI stays in control of the hardware (including physical memory allocation). Other reasons are performance (most drivers provided by UEFI are not optimized), control (not all device features are supported in UEFI), and compatibility (most operating systems want to run on non-UEFI systems too).

Even if most operating systems quickly use the ExitBootServices function to take over hardware control, there are still a few useful UEFI protocols that are useful when implementing a bootloader. In the following, we present a few useful protocols and show how to use them.

Memory Allocation

As already mentioned above, the UEFI firmware is in control of memory until we use ExitBootServices. To supply additional memory to applications, the UEFI standard defines different memory allocation functions, which are defined in section 6.2 of the standard (PDF). The uefi crate supports them too: We have to use the SystemTable::boot_services function to get access to the BootServices table. Then we can call the allocate_pool method to allocate a number of bytes from a UEFI-managed memory pool. Alternatively, we can allocate a number of 4KiB pages through allocate_pages. To free allocated memory again, we can use the free_pool and free_pages methods.

Using these methods, it is possible to create a Rust-compatible GlobalAlloc, which allows linking the alloc crate (see the other posts on this blog). The uefi crate already provides such an allocator if we enable its alloc feature:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

uefi = { version = "0.8.0", features = ["alloc"] }

Now we can use the alloc crate in our UEFI application:

// in src/main.rs

// the `alloc_error_handler` attribute is still unstable

#![feature(alloc_error_handler)]

// link the alloc crate

extern crate alloc;

use alloc::vec::Vec;

#[entry]

fn efi_main(

image: uefi::Handle,

system_table: uefi::table::SystemTable<uefi::table::Boot>,

) -> uefi::Status {

// ... (as before)

// initialize the allocator

unsafe {

uefi::alloc::init(system_table.boot_services());

}

// we can now use the allocator

let mut v = Vec::new();

v.push(1);

v.push(2);

writeln!(stdout, "v = {:?}", v).unwrap();

loop {}

}

/// This function is called when an allocation fails,

/// typically because the system is out of memory.

#[alloc_error_handler]

fn alloc_error(_layout: Layout) -> ! {

panic!("out of memory")

}

To compile it, we need a slight modification to our build command since the alloc crate needs to be cross-compiled for our UEFI target as well:

cargo build --target x86_64-unknown-uefi -Z build-std=core,alloc \

-Z build-std-features=compiler-builtins-mem

The only change is that build-std is now set to core,alloc instead of just core.

Note that the UEFI-provided allocation functions are only usable until ExitBootServices is called. This is the reason that the uefi::alloc::init function requires unsafe.

Locating the ACPI Tables

The ACPI standard is used to discover and configure hardware devices. It consists of multiple tables that are placed somewhere in memory. To find out where in memory these tables are, we can use the UEFI configuration table, which is defined in section 4.6 of the standard (PDF). To access it with the uefi crate, we use the SystemTable::config_table method, which returns a slice of ConfigTableEntry structs. To find the relevant ACPI RSDP table, we look for an entry with a GUID that is equal to ACPI_GUID or ACPI2_GUID. The address field of that entry then tells us the memory address of the RSPD table.

Putting things together, the code can look like this:

use uefi::table::cfg;

let mut config_entries = system_table.config_table().iter();

let rsdp_addr = config_entries

.find(|entry| matches!(entry.guid, cfg::ACPI_GUID | cfg::ACPI2_GUID))

.map(|entry| entry.address);

We won't do anything with RSDP table here, but bootloaders typically provide it to loaded kernels, e.g. via the boot information structure they send.

Graphics Output

As noted above, the text-based output protocol is only available until exiting UEFI boot services. Another drawback of it is that in only provides a text-based interface instead of allowing to set individual pixels. Fortunately, UEFI also supports a Graphics Output Protocol (GOP) that fixes both of these problems. We can use it in the following way:

use uefi::proto::console::gop::GraphicsOutput;

let protocol = system_table.boot_services().locate_protocol::<GraphicsOutput>().unwrap();

let gop = unsafe { &mut *protocol.get()};

The locate_protocol method can be used to locate any protocol that implements the Protocol trait, including GraphicsOutput. Not all protocols are available on all systems though. In our case, we use unwrap to panic if the GOP protocol is not available.

Since the UEFI-provided functions are neither thread-safe nor reentrant, the locate_protocol method returns an &UnsafeCell, which is unsafe to access. We are sure that this is the first and only time that we use the GOP protocol, so we directly convert it to a &mut reference by using the UnsafeCell::get method and then converting the resulting *mut pointer via &mut *.

The GraphicsOutput type provides a wide range of functionality for configuring a pixel-based framebuffer. Through current_mode_info, modes, and set_mode we can query the currently active graphics mode, get a list of all supported modes, and enable a different mode. The frame_buffer method gives us direct access to the framebuffer through a FrameBuffer abstraction type. We can then read the raw pointer and size of the framebuffer via FrameBuffer::as_mut_ptr and FrameBuffer::size.

As already mentioned, the GOP framebuffer stays available even after exiting boot services. Thus we can simply pass the framebuffer pointer, its mode info, and its size to the kernel, which can then easily write to screen, as we show in our [TODO] post.

Physical Memory Map

When the kernel takes control of memory management, it needs to know which physical memory areas are freely usable, which are still in use, and which are reserved by some hardware devices. To query this memory map from the UEFI firmware, we can use the SystemTable::memory_map method. However the resulting memory map might still change as long as the UEFI firmware has control over memory and we still call other UEFI functions. For this reason, the UEFI firmware also returns an up-to-date memory map when exiting boot services, which is the recommended way of retrieving the memory map.

To use the exit_boot_services, we need to provide a buffer that is big enough to hold the memory map. To find out how large the buffer needs to be, we can use the BootServices::memory_map_size method. Then we can use the allocate_pool method to allocate a buffer region of that size. However, since the allocate_pool call might change the memory map, it might become a bit larger than returned by memory_map_size. For this reason, we need to allocate a bit extra space. This can be implemented in the following way:

use uefi::table::boot::{MemoryDescriptor, MemoryType};

let mmap_storage = {

let max_mmap_size = system_table.boot_services().memory_map_size()

+ 8 * mem::size_of::<MemoryDescriptor>();

let ptr = system_table

.boot_services()

.allocate_pool(MemoryType::LOADER_DATA, max_mmap_size)?

.unwrap();

unsafe { slice::from_raw_parts_mut(ptr, max_mmap_size) }

};

let (system_table, memory_map) = system_table

.exit_boot_services(image, mmap_storage).unwrap()

This returns a new SystemTable instance that no longer provides access to the boot services. The memory_map return type is an iterator of MemoryDescriptor instances, which describe the physical start address, size, and type of each memory region.

Note that we also need to call uefi::alloc::exit_boot_services() before exiting boot services to uninitialize the heap allocator again. Otherwise undefined behavior might occur if we accidentally use the alloc crate again afterwards.

Creating a Bootloader

Loading the Kernel

We already saw how to set up a framebuffer for screen output and query the physical memory map and the APIC base register address. This is already all the system information that a basic kernel needs from the bootloader.

The next step is to load the kernel executable. This involves loading the kernel from disk into memory, allocating a stack for it, and setting up a new page table hierarchy to properly map it to virtual memory.

Loading it from Disk

One approach for including our kernel could be to place it in the FAT partition created by our disk_image crate. Then we could use the TODO protocol of the uefi crate to load it from disk into memory.

To keep things simple, we will use a different appoach here. Instead of loading the kernel separately, we place its bytes as a static variable inside our bootloader executable. This way, the UEFI firmware directly loads it into memory when launching the bootloader. To implement this, we can use the [include_bytes] macro of Rust's core library:

// TODO

Parsing the Kernel

Now that we have our kernel executable in memory, we need to parse it. In the following, we assume that the kernel uses the ELF executable format, which is popular in the Linux world. This is also the excutable format that the kernel created in this blog series uses.

The ELF format is structured like this:

TODO

The various headers are useful in different situations. For loading the executable into memory, the program header is most relevant. It looks like this:

TODO

TODO: mention readelf/objdump/etc for looking at program header

There are already a number of ELF parsing crates in the Rust ecosystem, so we don't need to create our own. In the following, we will use the [xmas_elf] crate, but other crates might work equally well.

TODO: load program segements and print them

TODO: .bss section -> mem_size might be larger than file_size

Page Table Mappings

TODO:

- create new page table - map each segment - special-case: mem_size > file_size

Create a Stack

Switching to Kernel

Challenges

Boot Information

- Physical Memory