49 KiB

+++ title = "ヒープ割り当て" weight = 10 path = "ja/heap-allocation" date = 2019-06-26

[extra] chapter = "Memory Management" translation_based_on_commit = "" translators = ["woodyZootopia"] +++

この記事では、私たちのカーネルにヒープ割り当ての機能を追加します。まず動的メモリの基礎を説明し、いかにして借用チェッカがありがちなアロケーションエラーを防ぐのかを示します。その後Rustの基礎的なアロケーションインターフェースを実装し、ヒープメモリ領域を作成し、アロケータクレートを作成します。この記事を終える頃には、Rustに組み込みのallocクレートのすべてのアロケーション・コレクション型が私たちのカーネルで利用可能になっているでしょう。

このブログの内容は GitHub 上で公開・開発されています。何か問題や質問などがあれば issue をたててください (訳注: リンクは原文(英語)のものになります)。またこちらにコメントを残すこともできます。この記事の完全なソースコードはpost-10 ブランチにあります。

TODO:translation_based_on_commitを埋める

TODO:リンクを日本語記事の物に変更する

ローカル変数とスタティック変数

私たちのカーネルでは現在二種類の変数が使用されています:ローカル変数とstatic変数です。ローカル変数はコールスタックに格納されており、変数の定義された関数がリターンするまでの間のみ有効です。スタティック変数はメモリ上の固定された場所に格納されており、プログラムのライフタイム全体で常に生存します。

ローカル変数

ローカル変数はコールスタックに格納されています。これはpushとpopという命令をサポートするスタックというデータ構造です。関数に入るたびに、パラメータ、リターンアドレス、呼び出された関数のローカル変数がコンパイラによってpushされます:

上の例は、outer関数がinner関数を呼び出した後のコールスタックを示しています。コールスタックはouterのローカル変数を先に持っていることが分かります。innerを呼び出すと、パラメータ1とこの関数のリターンアドレスがpushされます。そこで制御はinnerへと移り、innerは自身のローカル変数をpushします。

inner関数がリターンした後で、コールスタックのその関数の部分がpopされ、outerのローカル変数のみが残ります:

inner関数のローカル変数はリターンまでしか生存していないことが分かります。Rustコンパイラはこの生存期間を強制し、私たちが値を長く使いすぎてしまうとエラーを投げます。例えば、ローカル変数への参照を返そうとすると:

fn inner(i: usize) -> &'static u32 {

let z = [1, 2, 3];

&z[i]

}

(run the example on the playground)

この例で参照を返そうとすることには意味がありませんが、変数に関数よりも長く生存して欲しいというケースは存在します。すでに私たちのカーネルでそのようなケースに遭遇しています。割り込み記述子表をロードしようとしたときで、ライフタイムを延ばすためにstatic変数を使う必要があったのでした。

スタティック変数

スタティック変数は、スタックとは別の固定されたメモリ位置に格納されます。このメモリ位置はコンパイル時にリンカによって指定され、実行可能ファイルにエンコードされています。スタティック変数はプログラムの実行中ずっと生存するため、'staticライフタイムを持っており、ローカル変数によっていつでも参照されることができます。

上の例でinner関数がリターンするとき、それに対応するコールスタックは破棄されます。スタティック変数は絶対に破棄されない別のメモリ領域にあるため、参照&Z[1]はリターン後も有効です。

'staticライフタイムの他にもスタティック変数には利点があります:位置がコンパイル時に分かるため、アクセスするために参照が必要ないのです。この特性を私たちのprintlnマクロに利用しました:スタティックなWriterを内部で使うことで、マクロを呼び出す際に&mut Writerが必要でなくなるのですが、これは他の変数にアクセスできない例外処理においてとても便利なのです。

しかし、スタティック変数のこの特性には重大な欠点がついてきます:デフォルトでは読み込み専用なのです。Rustがこのルールを強制するのは、例えば二つのスレッドがあるスタティック変数を同時に変更した場合データ競合が発生するためです。スタティック変数を変更する唯一の方法は、それをMutex型にカプセル化し、あらゆる時刻において&mut参照が一つしか存在しないことを保証することです。MutexはすでにスタティックなVGAバッファへのWriterを作ったときに使いました。

動的メモリ

ローカル変数とスタティック変数を組み合わせれば、それら自体とても強力であり、殆どのユースケースを満足します。しかし、両方に制限が存在することも見てきました:

- ローカル変数はそれを定義する関数やブロックが終わるまでしか生存しません。なぜなら、これらはコールスタックに存在し、関数がリターンした段階で破棄されるからです。

- スタティック変数はプログラムの実行中常に生存するため、必要なくなったときでもメモリを取り戻したり再利用したりする方法がありません。また、所有権のセマンティクスが不明瞭であり、すべての関数からアクセスできてしまうため、変更しようと思ったときには

Mutexで保護してやらないといけません。

ローカル・スタティック変数の制約としてもう一つ、固定サイズであることが挙げられます。従ってこれらは要素が追加されたときに動的に大きくなるコレクションを格納することができません(Rustにおいて動的サイズのローカル変数を可能にするunsized rvaluesの提案が行われていますが、これはいくつかの特定のケースでしかうまく動きません)。

これらの欠点を回避するために、プログラミング言語はしばしば、変数を格納するための第三の領域であるヒープをサポートします。ヒープは、allocateとdeallocateという二つの関数を通じて、実行時の動的メモリ割り当てをサポートします。以下のように:allocate関数は、変数を格納するのに使える、指定されたサイズの解放されたメモリの塊を返します。この変数は、deallocate関数をその変数への参照を引数に呼び出すことによって解放されるまで生存します。

例を使って見てみましょう:

ここでinner関数はzを格納するためにスタティック変数ではなくヒープメモリを使っています。まず要求されたサイズのメモリブロックを割り当て、*mut u32の生ポインタを返されます。その後でptr::writeメソッドを使って配列[1,2,3]をこれに書き込みます。最後のステップとして、offset関数を使ってi番目の要素へのポインタを計算しそれを返します(簡単のため、必要なキャストやunsafeブロックをいくつか省略しました)。

割り当てられたメモリはdeallocateの呼び出しによって明示的に解放されるまで生存します。したがって、返されたポインタはinnerがリターンし、コールスタックの対応する部分が破棄された後も有効です。スタティックメモリと比較したときのヒープメモリの長所は、解放後に再利用できると言うことです(outer内のdeallocate呼び出しでまさにこれを行っています)。この呼び出しの後、状況は以下のようになります。

z[1]スロットが再び解放され、次のallocate呼び出しで再利用できることが分かります。しかし、z[0]とz[2]は永久にdeallocateされず、したがって永久に解放されないことも分かります。このようなバグはメモリリークと呼ばれており、しばしばプログラムによる過剰なメモリ消費を引き起こします(innerをループ内で何度も呼び出したらどんなことになるか、想像してみてください)。これ自体良くないことに思われるかもしれませんが、実は動的割り当てでは遙かに危険性の高いバグも発生しうるのです。

Common Errors

Apart from memory leaks, which are unfortunate but don't make the program vulnerable to attackers, there are two common types of bugs with more severe consequences:

- When we accidentally continue to use a variable after calling

deallocateon it, we have a so-called use-after-free vulnerability. Such a bug causes undefined behavior and can often be exploited by attackers to execute arbitrary code. - When we accidentally free a variable twice, we have a double-free vulnerability. This is problematic because it might free a different allocation that was allocated in the same spot after the first

deallocatecall. Thus, it can lead to an use-after-free vulnerability again.

These types of vulnerabilities are commonly known, so one might expect that people learned how to avoid them by now. But no, such vulnerabilities are still regularly found, for example this recent use-after-free vulnerability in Linux that allowed arbitrary code execution. This shows that even the best programmers are not always able to correctly handle dynamic memory in complex projects.

To avoid these issues, many languages such as Java or Python manage dynamic memory automatically using a technique called garbage collection. The idea is that the programmer never invokes deallocate manually. Instead, the program is regularly paused and scanned for unused heap variables, which are then automatically deallocated. Thus, the above vulnerabilities can never occur. The drawbacks are the performance overhead of the regular scan and the probably long pause times.

Rust takes a different approach to the problem: It uses a concept called ownership that is able to check the correctness of dynamic memory operations at compile time. Thus no garbage collection is needed to avoid the mentioned vulnerabilities, which means that there is no performance overhead. Another advantage of this approach is that the programmer still has fine-grained control over the use of dynamic memory, just like with C or C++.

Allocations in Rust

Instead of letting the programmer manually call allocate and deallocate, the Rust standard library provides abstraction types that call these functions implicitly. The most important type is Box, which is an abstraction for a heap-allocated value. It provides a Box::new constructor function that takes a value, calls allocate with the size of the value, and then moves the value to the newly allocated slot on the heap. To free the heap memory again, the Box type implements the Drop trait to call deallocate when it goes out of scope:

{

let z = Box::new([1,2,3]);

[…]

} // z goes out of scope and `deallocate` is called

This pattern has the strange name resource acquisition is initialization (or RAII for short). It originated in C++, where it is used to implement a similar abstraction type called std::unique_ptr.

Such a type alone does not suffice to prevent all use-after-free bugs since programmers can still hold on to references after the Box goes out of scope and the corresponding heap memory slot is deallocated:

let x = {

let z = Box::new([1,2,3]);

&z[1]

}; // z goes out of scope and `deallocate` is called

println!("{}", x);

This is where Rust's ownership comes in. It assigns an abstract lifetime to each reference, which is the scope in which the reference is valid. In the above example, the x reference is taken from the z array, so it becomes invalid after z goes out of scope. When you run the above example on the playground you see that the Rust compiler indeed throws an error:

error[E0597]: `z[_]` does not live long enough

--> src/main.rs:4:9

|

2 | let x = {

| - borrow later stored here

3 | let z = Box::new([1,2,3]);

4 | &z[1]

| ^^^^^ borrowed value does not live long enough

5 | }; // z goes out of scope and `deallocate` is called

| - `z[_]` dropped here while still borrowed

The terminology can be a bit confusing at first. Taking a reference to a value is called borrowing the value since it's similar to a borrow in real life: You have temporary access to an object but need to return it sometime and you must not destroy it. By checking that all borrows end before an object is destroyed, the Rust compiler can guarantee that no use-after-free situation can occur.

Rust's ownership system goes even further and does not only prevent use-after-free bugs, but provides complete memory safety like garbage collected languages like Java or Python do. Additionally, it guarantees thread safety and is thus even safer than those languages in multi-threaded code. And most importantly, all these checks happen at compile time, so there is no runtime overhead compared to hand written memory management in C.

Use Cases

We now know the basics of dynamic memory allocation in Rust, but when should we use it? We've come really far with our kernel without dynamic memory allocation, so why do we need it now?

First, dynamic memory allocation always comes with a bit of performance overhead, since we need to find a free slot on the heap for every allocation. For this reason local variables are generally preferable, especially in performance sensitive kernel code. However, there are cases where dynamic memory allocation is the best choice.

As a basic rule, dynamic memory is required for variables that have a dynamic lifetime or a variable size. The most important type with a dynamic lifetime is Rc, which counts the references to its wrapped value and deallocates it after all references went out of scope. Examples for types with a variable size are Vec, String, and other collection types that dynamically grow when more elements are added. These types work by allocating a larger amount of memory when they become full, copying all elements over, and then deallocating the old allocation.

For our kernel we will mostly need the collection types, for example for storing a list of active tasks when implementing multitasking in future posts.

The Allocator Interface

The first step in implementing a heap allocator is to add a dependency on the built-in alloc crate. Like the core crate, it is a subset of the standard library that additionally contains the allocation and collection types. To add the dependency on alloc, we add the following to our lib.rs:

// in src/lib.rs

extern crate alloc;

Contrary to normal dependencies, we don't need to modify the Cargo.toml. The reason is that the alloc crate ships with the Rust compiler as part of the standard library, so the compiler already knows about the crate. By adding this extern crate statement, we specify that the compiler should try to include it. (Historically, all dependencies needed an extern crate statement, which is now optional).

Since we are compiling for a custom target, we can't use the precompiled version of alloc that is shipped with the Rust installation. Instead, we have to tell cargo to recompile the crate from source. We can do that, by adding it to the unstable.build-std array in our .cargo/config.toml file:

# in .cargo/config.toml

[unstable]

build-std = ["core", "compiler_builtins", "alloc"]

Now the compiler will recompile and include the alloc crate in our kernel.

The reason that the alloc crate is disabled by default in #[no_std] crates is that it has additional requirements. We can see these requirements as errors when we try to compile our project now:

error: no global memory allocator found but one is required; link to std or add

#[global_allocator] to a static item that implements the GlobalAlloc trait.

error: `#[alloc_error_handler]` function required, but not found

The first error occurs because the alloc crate requires an heap allocator, which is an object that provides the allocate and deallocate functions. In Rust, heap allocators are described by the GlobalAlloc trait, which is mentioned in the error message. To set the heap allocator for the crate, the #[global_allocator] attribute must be applied to a static variable that implements the GlobalAlloc trait.

The second error occurs because calls to allocate can fail, most commonly when there is no more memory available. Our program must be able to react to this case, which is what the #[alloc_error_handler] function is for.

We will describe these traits and attributes in detail in the following sections.

The GlobalAlloc Trait

The GlobalAlloc trait defines the functions that a heap allocator must provide. The trait is special because it is almost never used directly by the programmer. Instead, the compiler will automatically insert the appropriate calls to the trait methods when using the allocation and collection types of alloc.

Since we will need to implement the trait for all our allocator types, it is worth taking a closer look at its declaration:

pub unsafe trait GlobalAlloc {

unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8;

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout);

unsafe fn alloc_zeroed(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8 { ... }

unsafe fn realloc(

&self,

ptr: *mut u8,

layout: Layout,

new_size: usize

) -> *mut u8 { ... }

}

It defines the two required methods alloc and dealloc, which correspond to the allocate and deallocate functions we used in our examples:

- The

allocmethod takes aLayoutinstance as argument, which describes the desired size and alignment that the allocated memory should have. It returns a raw pointer to the first byte of the allocated memory block. Instead of an explicit error value, theallocmethod returns a null pointer to signal an allocation error. This is a bit non-idiomatic, but it has the advantage that wrapping existing system allocators is easy, since they use the same convention. - The

deallocmethod is the counterpart and responsible for freeing a memory block again. It receives two arguments, the pointer returned byallocand theLayoutthat was used for the allocation.

The trait additionally defines the two methods alloc_zeroed and realloc with default implementations:

- The

alloc_zeroedmethod is equivalent to callingallocand then setting the allocated memory block to zero, which is exactly what the provided default implementation does. An allocator implementation can override the default implementations with a more efficient custom implementation if possible. - The

reallocmethod allows to grow or shrink an allocation. The default implementation allocates a new memory block with the desired size and copies over all the content from the previous allocation. Again, an allocator implementation can probably provide a more efficient implementation of this method, for example by growing/shrinking the allocation in-place if possible.

Unsafety

One thing to notice is that both the trait itself and all trait methods are declared as unsafe:

- The reason for declaring the trait as

unsafeis that the programmer must guarantee that the trait implementation for an allocator type is correct. For example, theallocmethod must never return a memory block that is already used somewhere else because this would cause undefined behavior. - Similarly, the reason that the methods are

unsafeis that the caller must ensure various invariants when calling the methods, for example that theLayoutpassed toallocspecifies a non-zero size. This is not really relevant in practice since the methods are normally called directly by the compiler, which ensures that the requirements are met.

A DummyAllocator

Now that we know what an allocator type should provide, we can create a simple dummy allocator. For that we create a new allocator module:

// in src/lib.rs

pub mod allocator;

Our dummy allocator does the absolute minimum to implement the trait and always return an error when alloc is called. It looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

use alloc::alloc::{GlobalAlloc, Layout};

use core::ptr::null_mut;

pub struct Dummy;

unsafe impl GlobalAlloc for Dummy {

unsafe fn alloc(&self, _layout: Layout) -> *mut u8 {

null_mut()

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, _ptr: *mut u8, _layout: Layout) {

panic!("dealloc should be never called")

}

}

The struct does not need any fields, so we create it as a zero sized type. As mentioned above, we always return the null pointer from alloc, which corresponds to an allocation error. Since the allocator never returns any memory, a call to dealloc should never occur. For this reason we simply panic in the dealloc method. The alloc_zeroed and realloc methods have default implementations, so we don't need to provide implementations for them.

We now have a simple allocator, but we still have to tell the Rust compiler that it should use this allocator. This is where the #[global_allocator] attribute comes in.

The #[global_allocator] Attribute

The #[global_allocator] attribute tells the Rust compiler which allocator instance it should use as the global heap allocator. The attribute is only applicable to a static that implements the GlobalAlloc trait. Let's register an instance of our Dummy allocator as the global allocator:

// in src/allocator.rs

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOCATOR: Dummy = Dummy;

Since the Dummy allocator is a zero sized type, we don't need to specify any fields in the initialization expression.

When we now try to compile it, the first error should be gone. Let's fix the remaining second error:

error: `#[alloc_error_handler]` function required, but not found

The #[alloc_error_handler] Attribute

As we learned when discussing the GlobalAlloc trait, the alloc function can signal an allocation error by returning a null pointer. The question is: how should the Rust runtime react to such an allocation failure? This is where the #[alloc_error_handler] attribute comes in. It specifies a function that is called when an allocation error occurs, similar to how our panic handler is called when a panic occurs.

Let's add such a function to fix the compilation error:

// in src/lib.rs

#![feature(alloc_error_handler)] // at the top of the file

#[alloc_error_handler]

fn alloc_error_handler(layout: alloc::alloc::Layout) -> ! {

panic!("allocation error: {:?}", layout)

}

The alloc_error_handler function is still unstable, so we need a feature gate to enable it. The function receives a single argument: the Layout instance that was passed to alloc when the allocation failure occurred. There's nothing we can do to resolve the failure, so we just panic with a message that contains the Layout instance.

With this function, the compilation errors should be fixed. Now we can use the allocation and collection types of alloc, for example we can use a Box to allocate a value on the heap:

// in src/main.rs

extern crate alloc;

use alloc::boxed::Box;

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// […] print "Hello World!", call `init`, create `mapper` and `frame_allocator`

let x = Box::new(41);

// […] call `test_main` in test mode

println!("It did not crash!");

blog_os::hlt_loop();

}

Note that we need to specify the extern crate alloc statement in our main.rs too. This is required because the lib.rs and main.rs part are treated as separate crates. However, we don't need to create another #[global_allocator] static because the global allocator applies to all crates in the project. In fact, specifying an additional allocator in another crate would be an error.

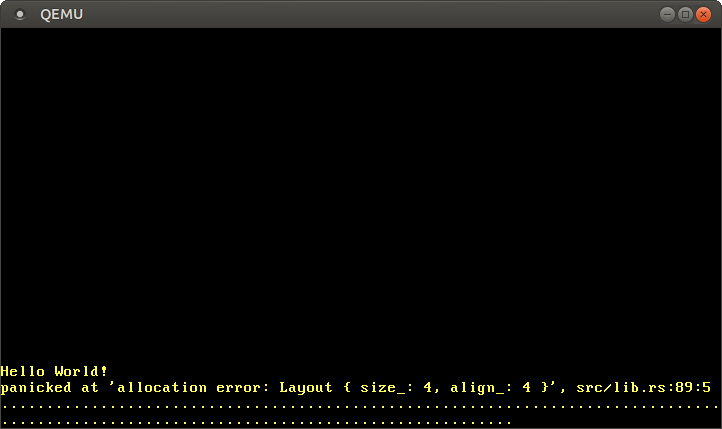

When we run the above code, we see that our alloc_error_handler function is called:

The error handler is called because the Box::new function implicitly calls the alloc function of the global allocator. Our dummy allocator always returns a null pointer, so every allocation fails. To fix this we need to create an allocator that actually returns usable memory.

Creating a Kernel Heap

Before we can create a proper allocator, we first need to create a heap memory region from which the allocator can allocate memory. To do this, we need to define a virtual memory range for the heap region and then map this region to physical frames. See the "Introduction To Paging" post for an overview of virtual memory and page tables.

The first step is to define a virtual memory region for the heap. We can choose any virtual address range that we like, as long as it is not already used for a different memory region. Let's define it as the memory starting at address 0x_4444_4444_0000 so that we can easily recognize a heap pointer later:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub const HEAP_START: usize = 0x_4444_4444_0000;

pub const HEAP_SIZE: usize = 100 * 1024; // 100 KiB

We set the heap size to 100 KiB for now. If we need more space in the future, we can simply increase it.

If we tried to use this heap region now, a page fault would occur since the virtual memory region is not mapped to physical memory yet. To resolve this, we create an init_heap function that maps the heap pages using the Mapper API that we introduced in the "Paging Implementation" post:

// in src/allocator.rs

use x86_64::{

structures::paging::{

mapper::MapToError, FrameAllocator, Mapper, Page, PageTableFlags, Size4KiB,

},

VirtAddr,

};

pub fn init_heap(

mapper: &mut impl Mapper<Size4KiB>,

frame_allocator: &mut impl FrameAllocator<Size4KiB>,

) -> Result<(), MapToError<Size4KiB>> {

let page_range = {

let heap_start = VirtAddr::new(HEAP_START as u64);

let heap_end = heap_start + HEAP_SIZE - 1u64;

let heap_start_page = Page::containing_address(heap_start);

let heap_end_page = Page::containing_address(heap_end);

Page::range_inclusive(heap_start_page, heap_end_page)

};

for page in page_range {

let frame = frame_allocator

.allocate_frame()

.ok_or(MapToError::FrameAllocationFailed)?;

let flags = PageTableFlags::PRESENT | PageTableFlags::WRITABLE;

unsafe {

mapper.map_to(page, frame, flags, frame_allocator)?.flush()

};

}

Ok(())

}

The function takes mutable references to a Mapper and a FrameAllocator instance, both limited to 4KiB pages by using Size4KiB as generic parameter. The return value of the function is a Result with the unit type () as success variant and a MapToError as error variant, which is the error type returned by the Mapper::map_to method. Reusing the error type makes sense here because the map_to method is the main source of errors in this function.

The implementation can be broken down into two parts:

-

Creating the page range:: To create a range of the pages that we want to map, we convert the

HEAP_STARTpointer to aVirtAddrtype. Then we calculate the heap end address from it by adding theHEAP_SIZE. We want an inclusive bound (the address of the last byte of the heap), so we subtract 1. Next, we convert the addresses intoPagetypes using thecontaining_addressfunction. Finally, we create a page range from the start and end pages using thePage::range_inclusivefunction. -

Mapping the pages: The second step is to map all pages of the page range we just created. For that we iterate over the pages in that range using a

forloop. For each page, we do the following:-

We allocate a physical frame that the page should be mapped to using the

FrameAllocator::allocate_framemethod. This method returnsNonewhen there are no more frames left. We deal with that case by mapping it to aMapToError::FrameAllocationFailederror through theOption::ok_ormethod and then apply the question mark operator to return early in the case of an error. -

We set the required

PRESENTflag and theWRITABLEflag for the page. With these flags both read and write accesses are allowed, which makes sense for heap memory. -

We use the

Mapper::map_tomethod for creating the mapping in the active page table. The method can fail, therefore we use the question mark operator again to forward the error to the caller. On success, the method returns aMapperFlushinstance that we can use to update the translation lookaside buffer using theflushmethod.

-

The final step is to call this function from our kernel_main:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

use blog_os::allocator; // new import

use blog_os::memory::{self, BootInfoFrameAllocator};

println!("Hello World{}", "!");

blog_os::init();

let phys_mem_offset = VirtAddr::new(boot_info.physical_memory_offset);

let mut mapper = unsafe { memory::init(phys_mem_offset) };

let mut frame_allocator = unsafe {

BootInfoFrameAllocator::init(&boot_info.memory_map)

};

// new

allocator::init_heap(&mut mapper, &mut frame_allocator)

.expect("heap initialization failed");

let x = Box::new(41);

// […] call `test_main` in test mode

println!("It did not crash!");

blog_os::hlt_loop();

}

We show the full function for context here. The only new lines are the blog_os::allocator import and the call to allocator::init_heap function. In case the init_heap function returns an error, we panic using the Result::expect method since there is currently no sensible way for us to handle this error.

We now have a mapped heap memory region that is ready to be used. The Box::new call still uses our old Dummy allocator, so you will still see the "out of memory" error when you run it. Let's fix this by using a proper allocator.

Using an Allocator Crate

Since implementing an allocator is somewhat complex, we start by using an external allocator crate. We will learn how to implement our own allocator in the next post.

A simple allocator crate for no_std applications is the linked_list_allocator crate. It's name comes from the fact that it uses a linked list data structure to keep track of deallocated memory regions. See the next post for a more detailed explanation of this approach.

To use the crate, we first need to add a dependency on it in our Cargo.toml:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

linked_list_allocator = "0.9.0"

Then we can replace our dummy allocator with the allocator provided by the crate:

// in src/allocator.rs

use linked_list_allocator::LockedHeap;

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOCATOR: LockedHeap = LockedHeap::empty();

The struct is named LockedHeap because it uses the spinning_top::Spinlock type for synchronization. This is required because multiple threads could access the ALLOCATOR static at the same time. As always when using a spinlock or a mutex, we need to be careful to not accidentally cause a deadlock. This means that we shouldn't perform any allocations in interrupt handlers, since they can run at an arbitrary time and might interrupt an in-progress allocation.

Setting the LockedHeap as global allocator is not enough. The reason is that we use the empty constructor function, which creates an allocator without any backing memory. Like our dummy allocator, it always returns an error on alloc. To fix this, we need to initialize the allocator after creating the heap:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub fn init_heap(

mapper: &mut impl Mapper<Size4KiB>,

frame_allocator: &mut impl FrameAllocator<Size4KiB>,

) -> Result<(), MapToError<Size4KiB>> {

// […] map all heap pages to physical frames

// new

unsafe {

ALLOCATOR.lock().init(HEAP_START, HEAP_SIZE);

}

Ok(())

}

We use the lock method on the inner spinlock of the LockedHeap type to get an exclusive reference to the wrapped Heap instance, on which we then call the init method with the heap bounds as arguments. It is important that we initialize the heap after mapping the heap pages, since the init function already tries to write to the heap memory.

After initializing the heap, we can now use all allocation and collection types of the built-in alloc crate without error:

// in src/main.rs

use alloc::{boxed::Box, vec, vec::Vec, rc::Rc};

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// […] initialize interrupts, mapper, frame_allocator, heap

// allocate a number on the heap

let heap_value = Box::new(41);

println!("heap_value at {:p}", heap_value);

// create a dynamically sized vector

let mut vec = Vec::new();

for i in 0..500 {

vec.push(i);

}

println!("vec at {:p}", vec.as_slice());

// create a reference counted vector -> will be freed when count reaches 0

let reference_counted = Rc::new(vec![1, 2, 3]);

let cloned_reference = reference_counted.clone();

println!("current reference count is {}", Rc::strong_count(&cloned_reference));

core::mem::drop(reference_counted);

println!("reference count is {} now", Rc::strong_count(&cloned_reference));

// […] call `test_main` in test context

println!("It did not crash!");

blog_os::hlt_loop();

}

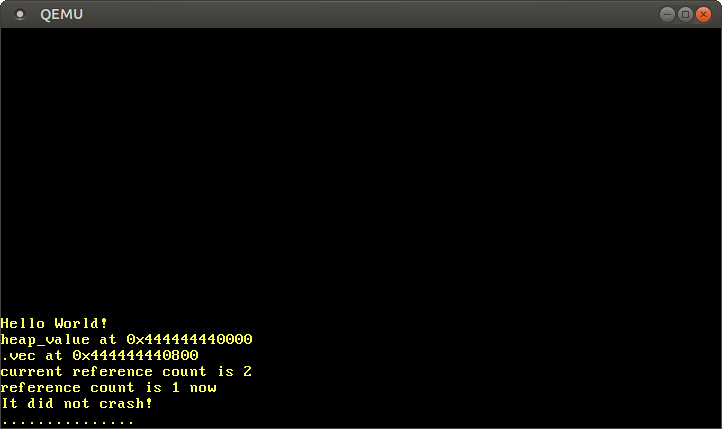

This code example shows some uses of the Box, Vec, and Rc types. For the Box and Vec types we print the underlying heap pointers using the {:p} formatting specifier. For showcasing Rc, we create a reference counted heap value and use the Rc::strong_count function to print the current reference count, before and after dropping an instance (using core::mem::drop).

When we run it, we see the following:

As expected, we see that the Box and Vec values live on the heap, as indicated by the pointer starting with the 0x_4444_4444_* prefix. The reference counted value also behaves as expected, with the reference count being 2 after the clone call, and 1 again after one of the instances was dropped.

The reason that the vector starts at offset 0x800 is not that the boxed value is 0x800 bytes large, but the reallocations that occur when the vector needs to increase its capacity. For example, when the vector's capacity is 32 and we try to add the next element, the vector allocates a new backing array with capacity 64 behind the scenes and copies all elements over. Then it frees the old allocation.

Of course there are many more allocation and collection types in the alloc crate that we can now all use in our kernel, including:

- the thread-safe reference counted pointer

Arc - the owned string type

Stringand theformat!macro LinkedList- the growable ring buffer

VecDeque - the

BinaryHeappriority queue BTreeMapandBTreeSet

These types will become very useful when we want to implement thread lists, scheduling queues, or support for async/await.

Adding a Test

To ensure that we don't accidentally break our new allocation code, we should add an integration test for it. We start by creating a new tests/heap_allocation.rs file with the following content:

// in tests/heap_allocation.rs

#![no_std]

#![no_main]

#![feature(custom_test_frameworks)]

#![test_runner(blog_os::test_runner)]

#![reexport_test_harness_main = "test_main"]

extern crate alloc;

use bootloader::{entry_point, BootInfo};

use core::panic::PanicInfo;

entry_point!(main);

fn main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

unimplemented!();

}

#[panic_handler]

fn panic(info: &PanicInfo) -> ! {

blog_os::test_panic_handler(info)

}

We reuse the test_runner and test_panic_handler functions from our lib.rs. Since we want to test allocations, we enable the alloc crate through the extern crate alloc statement. For more information about the test boilerplate check out the Testing post.

The implementation of the main function looks like this:

// in tests/heap_allocation.rs

fn main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

use blog_os::allocator;

use blog_os::memory::{self, BootInfoFrameAllocator};

use x86_64::VirtAddr;

blog_os::init();

let phys_mem_offset = VirtAddr::new(boot_info.physical_memory_offset);

let mut mapper = unsafe { memory::init(phys_mem_offset) };

let mut frame_allocator = unsafe {

BootInfoFrameAllocator::init(&boot_info.memory_map)

};

allocator::init_heap(&mut mapper, &mut frame_allocator)

.expect("heap initialization failed");

test_main();

loop {}

}

It is very similar to the kernel_main function in our main.rs, with the differences that we don't invoke println, don't include any example allocations, and call test_main unconditionally.

Now we're ready to add a few test cases. First, we add a test that performs some simple allocations using Box and checks the allocated values, to ensure that basic allocations work:

// in tests/heap_allocation.rs

use alloc::boxed::Box;

#[test_case]

fn simple_allocation() {

let heap_value_1 = Box::new(41);

let heap_value_2 = Box::new(13);

assert_eq!(*heap_value_1, 41);

assert_eq!(*heap_value_2, 13);

}

Most importantly, this test verifies that no allocation error occurs.

Next, we iteratively build a large vector, to test both large allocations and multiple allocations (due to reallocations):

// in tests/heap_allocation.rs

use alloc::vec::Vec;

#[test_case]

fn large_vec() {

let n = 1000;

let mut vec = Vec::new();

for i in 0..n {

vec.push(i);

}

assert_eq!(vec.iter().sum::<u64>(), (n - 1) * n / 2);

}

We verify the sum by comparing it with the formula for the n-th partial sum. This gives us some confidence that the allocated values are all correct.

As a third test, we create ten thousand allocations after each other:

// in tests/heap_allocation.rs

use blog_os::allocator::HEAP_SIZE;

#[test_case]

fn many_boxes() {

for i in 0..HEAP_SIZE {

let x = Box::new(i);

assert_eq!(*x, i);

}

}

This test ensures that the allocator reuses freed memory for subsequent allocations since it would run out of memory otherwise. This might seem like an obvious requirement for an allocator, but there are allocator designs that don't do this. An example is the bump allocator design that will be explained in the next post.

Let's run our new integration test:

> cargo test --test heap_allocation

[…]

Running 3 tests

simple_allocation... [ok]

large_vec... [ok]

many_boxes... [ok]

All three tests succeeded! You can also invoke cargo test (without --test argument) to run all unit and integration tests.

Summary

This post gave an introduction to dynamic memory and explained why and where it is needed. We saw how Rust's borrow checker prevents common vulnerabilities and learned how Rust's allocation API works.

After creating a minimal implementation of Rust's allocator interface using a dummy allocator, we created a proper heap memory region for our kernel. For that we defined a virtual address range for the heap and then mapped all pages of that range to physical frames using the Mapper and FrameAllocator from the previous post.

Finally, we added a dependency on the linked_list_allocator crate to add a proper allocator to our kernel. With this allocator, we were able to use Box, Vec, and other allocation and collection types from the alloc crate.

What's next?

While we already added heap allocation support in this post, we left most of the work to the linked_list_allocator crate. The next post will show in detail how an allocator can be implemented from scratch. It will present multiple possible allocator designs, shows how to implement simple versions of them, and explain their advantages and drawbacks.

![The same outer/inner example with the difference that inner has a static Z: [u32; 3] = [1,2,3]; and returns a &Z[i] reference](/michaelkuc6/blog_os/media/commit/884247cb1d3f2a86bb24a8c4ed92cb58048ca14b/blog/content/edition-2/posts/10-heap-allocation/call-stack-static.svg)

![The inner function calls allocate(size_of([u32; 3])), writes z.write([1,2,3]);, and returns (z as *mut u32).offset(i). The outer function does deallocate(y, size_of(u32)) on the returned value y.](/michaelkuc6/blog_os/media/commit/884247cb1d3f2a86bb24a8c4ed92cb58048ca14b/blog/content/edition-2/posts/10-heap-allocation/call-stack-heap.svg)

![The call stack contains the local variables of outer, the heap contains z[0] and z[2], but no longer z[1].](/michaelkuc6/blog_os/media/commit/884247cb1d3f2a86bb24a8c4ed92cb58048ca14b/blog/content/edition-2/posts/10-heap-allocation/call-stack-heap-freed.svg)