72 KiB

+++ title = "Async/Await" weight = 12 path = "async-await" date = 0000-01-01

[extra] chapter = "Interrupts" +++

In this post we explore cooperative multitasking and the async/await feature of Rust. This will make it possible to run multiple concurrent tasks in our kernel. TODO

This blog is openly developed on GitHub. If you have any problems or questions, please open an issue there. You can also leave comments at the bottom. The complete source code for this post can be found in the post-12 branch.

Multitasking

One of the fundamental features of most operating systems is multitasking, which is the ability to execute multiple tasks concurrently. For example, you probably have other programs open while looking at this post, such as a text editor or a terminal window. Even if you have only a single browser window open, there are probably various background tasks for managing your desktop windows, checking for updates, or indexing files.

While it seems like all tasks run in parallel, only a single task can be executed on a CPU core at a time. To create the illusion that the tasks run in parallel, the operating system rapidly switches between active tasks so that each one can make a bit of progress. Since computers are fast, we don't notice these switches most of the time.

While single-core CPUs can only execute a single task at a time, multi-core CPUs can run multiple tasks in a truly parallel way. For example, a CPU with 8 cores can run 8 tasks at the same time. We will explain how to setup multi-core CPUs in a future post. For this post, we will focus on single-core CPUs for simplicity. (It's worth noting that all multi-core CPUs start with only a single active core, so we can treat them as single-core CPUs for now.)

There are two forms of multitasking: Cooperative multitasking requires tasks to regularly give up control of the CPU so that other tasks can make progress. Preemptive multitasking uses operating system functionality to switch threads at arbitrary points in time by forcibly pausing them. In the following we will explore the two forms of multitasking in more detail and discuss their respective advantages and drawbacks.

Preemptive Multitasking

The idea behind preemptive multitasking is that the operating system controls when to switch tasks. For that, it utilizes the fact that it regains control of the CPU on each interrupt. This makes it possible to switch tasks whenever new input is available to the system. For example, it would be possible to switch tasks when the mouse is moved or a network packet arrives. The operating system can also determine the exact time that a task is allowed to run by configuring a hardware timer to send an interrupt after that time.

The following graphic illustrates the task switching process on a hardware interrupt:

In the first row, the CPU is executing task A1 of program A. All other tasks are paused. In the second row, a hardware interrupt arrives at the CPU. As described in the Hardware Interrupts post, the CPU immediately stops the execution of task A1 and jumps to the interrupt handler defined in the interrupt descriptor table (IDT). Through this interrupt handler, the operating system now has control of the CPU again, which allows it to switch to task B1 instead of continuing task A1.

Saving State

Since tasks are interrupted at arbitrary points in time, they might be in the middle of some calculations. In order to be able to resume them later, the operating system must backup the whole state of the task, including its call stack and the values of all CPU registers. This process is called a context switch.

As the call stack can be very large, the operating system typically sets up a separate call stack for each task instead of backing up the call stack content on each task switch. Such a task with a separate stack is called a thread of execution or thread for short. By using a separate stack for each task, only the register contents need to be saved on a context switch (including the program counter and stack pointer). This approach minimizes the performance overhead of a context switch, which is very important since context switches often occur up to 100 times per second.

Discussion

The main advantage of preemptive multitasking is that the operating system can fully control the allowed execution time of a task. This way, it can guarantee that each task gets a fair share of the CPU time, without the need to trust the tasks to cooperate. This is especially important when running third-party tasks or when multiple users share a system.

The disadvantage of preemption is that each task requires its own stack. Compared to a shared stack, this results in a higher memory usage per task and often limits the number of tasks in the system. Another disadvantage is that the operating system always has to save the complete CPU register state on each task switch, even if the task only used a small subset of the registers.

Preemptive multitasking and threads are fundamental components of an operating system because they make it possible to run untrusted userspace programs. We will discuss these concepts in full detail in future posts. For this post, however, we will focus on cooperative multitasking, which also provides useful capabilities for our kernel.

Cooperative Multitasking

Instead of forcibly pausing running tasks at arbitrary points in time, cooperative multitasking lets each task run until it voluntarily gives up control of the CPU. This allows tasks to pause themselves at convenient points in time, for example when it needs to wait for an I/O operation anyway.

Cooperative multitasking is often used at the language level, for example in form of coroutines or async/await. The idea is that either the programmer or the compiler inserts yield operations into the program, which give up control of the CPU and allow other tasks to run. For example, a yield could be inserted after each iteration of a complex loop.

It is common to combine cooperative multitasking with asynchronous operations. Instead of waiting until an operation is finished and preventing other tasks to run in this time, asynchronous operations return a "not ready" status if the operation is not finished yet. In this case, the waiting task can execute a yield operation to let other tasks run.

Saving State

Since tasks define their pause points themselves, they don't need the operating system to save their state. Instead, they can save exactly the state they need for continuation before they pause themselves, which often results in better performance. For example, a task that just finished a complex computation might only need to backup the final result of the computation since it does not need the intermediate results anymore.

Language-supported implementations of cooperative tasks are often even able to backup up the required parts of the call stack before pausing. As an example, Rust's async/await implementation stores all local variables that are still needed in an automatically generated struct (see below). By backing up the relevant parts of the call stack before pausing, all tasks can share a single call stack, which results in a much smaller memory consumption per task. This makes it possible to create an almost arbitrary number of cooperative tasks without running out of memory.

Discussion

The drawback of cooperative multitasking is that an uncooperative task can potentially run for an unlimited amount of time. Thus, a malicious or buggy task can prevent other tasks from running and slow down or even block the whole system. For this reason, cooperative multitasking should only be used when all tasks are known to cooperate. As a counterexample, it's not a good idea to make the operating system rely on the cooperation of arbitrary userlevel programs.

However, the strong performance and memory benefits of cooperative multitasking make it a good approach for usage within a program, especially in combination with asynchronous operations. Since an operating system kernel is a performance-critical program that interacts with asynchronous hardware, cooperative multitasking seems like a good approach for concurrency in our kernel.

Async/Await in Rust

The Rust language provides first-class support for cooperative multitasking in form of async/await. Before we can explore what async/await is and how it works, we need to understand how futures and asynchronous programming work in Rust.

Futures

A future represents a value that might not be available yet. This could be for example an integer that is computed by another task or a file that is downloaded from the network. Instead of waiting until the value is available, futures make it possible to continue execution until the value is needed.

Example

The concept of futures is best illustrated with a small example:

This sequence diagram shows a main function that reads a file from the file system and then calls a function foo. This process is repeated two times: Once with a synchronous read_file call and once with an asynchronous async_read_file call.

With the synchronous call, the main function needs to wait until the file is loaded from the file system. Only then it can call the foo function, which requires it to again wait for the result.

With the asynchronous async_read_file call, the file system directly returns a future and loads the file asynchronously in the background. This allows the main function to call foo much earlier, which then runs in parallel with the file load. In this example, the file load even finishes before foo returns, so main can directly work with the file without further waiting after foo returns.

Futures in Rust

In Rust, futures are represented by the Future trait, which looks like this:

pub trait Future {

type Output;

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output>;

}

The associated type Output specfies the type of the asynchronous value. For example, the async_read_file function in the diagram above would return a Future instance with Output set to File.

The poll method allows to check if the value is already available. It returns a Poll enum, which looks like this:

pub enum Poll<T> {

Ready(T),

Pending,

}

When the value is already available (e.g. the file was fully read from disk), it is returned wrapped in the Ready variant. Otherwise, the Pending variant is returned, which signals the caller that the value is not yet available.

The poll method takes two arguments: self: Pin<&mut Self> and cx: &mut Context. The former behaves like a normal &mut self reference, with the difference that the Self value is pinned to its memory location. Understanding Pin and why it is needed is difficult without understanding how async/await works first. We will therefore explain it later in this post.

The purpose of the cx: &mut Context parameter is to pass a Waker instance to the asynchronous task, e.g. the file system load. This Waker allows the asynchronous task to signal that it (or a part of it) is finished, e.g. that the file was loaded from disk. Since the main task knows that it will be notified when the Future is ready, it does not need to call poll over and over again. We will explain this process in more detail later in this post when we implement an own waker type.

Working with Futures

We now know how futures are defined and understand the basic idea behind the poll method. However, we still don't know how to effectively work with futures. The problem is that futures represent results of asynchronous tasks, which might be not available yet. In practice, however, we often need these values directly for further calculations. So the question is: How can we efficiently retrieve the value of a future when we need it?

Waiting on Futures

One possible answer is to wait until a future becomes ready. This could look something like this:

let future = async_read_file("foo.txt");

let file_content = loop {

match future.poll(…) {

Poll::Ready(value) => break value,

Poll::Pending => {}, // do nothing

}

}

Here we actively wait for the future by calling poll over and over again in a loop. The arguments to poll don't matter here, so we omitted them. While this solution works, it is very inefficient because we keep the CPU busy until the value becomes available.

A more efficient approach could be to block the current thread until the future becomes available. This is of course only possible if you have threads, so this solution does not work for our kernel, at least not yet. Even on systems where blocking is supported, it is often not desired because it turns an asynchronous task into a synchronous task again, thereby inhibiting the potential performance benefits of parallel tasks.

Future Combinators

An alternative to waiting is to use future combinators. Future combinators are functions like map that allow chaining and combining futures together, similar to the functions on Iterator. Instead of waiting on the future, these combinators return a future themselves, which applies the mapping operation on poll.

As an example, a simple string_len combinator for converting Future<Output = String> to a Future<Output = usize> could look like this:

struct StringLen<F> {

inner_future: F,

}

impl<F> Future for StringLen<F> where Fut: Future<Output = String> {

type Output = usize;

fn poll(mut self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<T> {

match self.inner_future.poll(cx) {

Poll::Ready(s) => Poll::Ready(s.len()),

Poll::Pending => Poll::Pending,

}

}

}

fn string_len(string: impl Future<Output = String>)

-> impl Future<Output = usize>

{

StringLen {

inner_future: string,

}

}

// Usage

fn file_len() -> impl Future<Output = usize> {

let file_content_future = async_read_file("foo.txt");

string_len(file_content_future)

}

This code does not quite work because it does not handle pinning, but it suffices as an example. The basic idea is that the string_len function wraps a given Future instance into a new StringLen struct, which also implements Future. When the wrapped future is polled, it polls the inner future. If the value is not ready yet, Poll::Pending is returned from the wrapped future too. If the value is ready, the string is extracted from the Poll::Ready variant and its length is calculated. Afterwards, it is wrapped in Poll::Ready again and returned.

With this string_len function, we can calculate the length of an asynchronous string without waiting for it. Since the function returns a Future again, the caller can't work directly on the returned value, but needs to use combinator functions again. This way, the whole call graph becomes asynchronous and we can efficiently wait for multiple futures at once at some point, e.g. in the main function.

Manually writing combinator functions is difficult, therefore they are often provided by libraries. While the Rust standard library itself provides no combinator methods yet, the semi-official (and no_std compatible) futures crate does. Its FutureExt trait provides high-level combinator methods such as map or then, which can be used to manipulate the result with arbitrary closures.

Advantages

The big advantage of future combinators is that they keep the operations asynchronous. In combination with asynchronous I/O interfaces, this approach can lead to very high performance. The fact that future combinators are implemented as normal structs with trait implementations allows the compiler to excessively optimize them. For more details, see the Zero-cost futures in Rust post, which announced the addition of futures to the Rust ecosystem.

Drawbacks

While future combinators make it possible to write very efficient code, they can be difficult to use in some situations because of the type system and the closure based interface. For example, consider code like this:

fn example(min_len: usize) -> impl Future<Output = String> {

async_read_file("foo.txt").then(move |content| {

if content.len() < min_len {

Either::Left(async_read_file("bar.txt").map(|s| content + &s))

} else {

Either::Right(future::ready(content))

}

})

}

Here we read the file foo.txt and then use the then combinator to chain a second future based on the file content. If the content length is smaller than the given min_len, we read a different bar.txt file and append it to content using the map combinator. Otherwise we return only the content of foo.txt.

We need to use the move keyword for the closure passed to then because otherwise there would be a lifetime error for min_len. The reason for the Either wrapper is that if and else blocks must always have the same type. Since we return different future types in the blocks, we must use the wrapper type to unify them into a single type. The ready function wraps a value into a future, which is immediately ready. The function is required here because the Either wrapper expects that the wrapped value implements Future.

As you can imagine, this can quickly lead to very complex code for larger projects. It gets especially complicated if borrowing and different lifetimes are involved. For this reason, a lot of work was invested to add support for async/await to Rust, with the goal of making asynchronous code radically simpler to write.

The Async/Await Pattern

The idea behind async/await is to let the programmer write code that looks like normal synchronous code, but is turned into asynchronous code by the compiler. It works based on the two keywords async and await. The async keyword can be used in a function signature to turn a synchronous function into an asynchronous function that returns a future:

async fn foo() -> u32 {

0

}

// the above is roughly translated by the compiler to:

fn foo() -> impl Future<Output = u32> {

future::ready(0)

}

This keyword alone wouldn't be that useful. However, inside async functions, the await keyword can be used to retrieve the asynchronous value of a future:

async fn example(min_len: usize) -> String {

let content = async_read_file("foo.txt").await;

if content.len() < min_len {

content + &async_read_file("bar.txt").await

} else {

content

}

}

This function is a direct translation of the example function that used combinator functions from above. Using the .await operator, we can retrieve the value of a future without needing any closures or Either types. As a result, we can write our code like we write normal synchronous code, with the difference that this is still asynchronous code.

State Machine Transformation

What the compiler does behind this scenes is to transform the body of the async function into a state machine, with each .await call representing a different state. For the above example function, the compiler creates a state machine with the following four states:

Each state represents a different pause point of the function. The "Start" and "End" states represent the function at the beginning and end of its execution. The "Waiting on foo.txt" state represents that the function is currently waiting for the first async_read_file result. Similarly, the "Waiting on bar.txt" state represents the pause point where the function is waiting on the second async_read_file result.

The state machine implements the Future trait by making each poll call a possible state transition:

The diagram uses arrows to represent state switches and diamond shapes to represent alternative ways. For example, if the foo.txt file is not ready, the path marked with "no" is taken and the "Waiting on foo.txt" state is reached. Otherwise, the "yes" path is taken. The small red diamond without caption represents the if content.len() < 100 branch of the example function.

We see that the first poll call starts the function and lets it run until it reaches a future that is not ready yet. If all futures on the path are ready, the function can run till the "End" state, where it returns its result wrapped in Poll::Ready. Otherwise, the state machine enters a waiting state and returns Poll::Pending. On the next poll call, the state machine then starts from the last waiting state and retries the last operation.

Saving State

In order to be able to continue from the last waiting state, the state machine must save it internally. In addition, it must save all the variables that it needs to continue execution on the next poll call. This is where the compiler can really shine: Since it knows which variables are used when, it can automatically generate structs with exactly the variables that are needed.

As an example, the compiler generates structs like the following for the above example function:

// The `example` function again so that you don't have to scroll up

async fn example(min_len: usize) -> String {

let content = async_read_file("foo.txt").await;

if content.len() < min_len {

content + &async_read_file("bar.txt").await

} else {

content

}

}

// The compiler-generated state structs:

struct StartState {

min_len: usize,

}

struct WaitingOnFooTxtState {

min_len: usize,

foo_txt_future: impl Future<Output = String>,

}

struct WaitingOnBarTxtState {

content: String,

bar_txt_future: impl Future<Output = String>,

}

struct EndState {}

In the "start" and "Waiting on foo.txt" states, the min_len parameter needs to be stored because it is required for the comparison with content.len() later. The "Waiting on foo.txt" state additionally stores a foo_txt_future, which represents the future returned by the async_read_file call. This future needs to be polled again when the state machine continues, so it needs to be saved.

The "Waiting on bar.txt" state contains the content variable because it is needed for the string concatenation after bar.txt is ready. It also stores a bar_txt_future that represents the in-progress load of bar.txt. The struct does not contain the min_len variable because it is no longer needed after the content.len() comparison. In the "end" state, no variables are stored because the function did already run to completion.

Keep in mind that this is only an example for the code that the compiler could generate. The struct names and the field layout are an implementation detail and might be different.

The Full State Machine Type

While the exact compiler-generated code is an implementation detail, it helps in understanding to imagine how the generated state machine could look for the example function. We already defined the structs representing the different states and containing the required variables. To create a state machine on top of them, we can combine them into an enum:

enum ExampleStateMachine {

Start(StartState),

WaitingOnFooTxt(WaitingOnFooTxtState),

WaitingOnBarTxt(WaitingOnBarTxtState),

End(EndState),

}

We define a separate enum variant for each state and add the corresponding state struct to each variant as a field. To implement the state transitions, the compiler generates an implementation of the Future trait based on the example function:

impl Future for ExampleStateMachine {

type Output = String; // return type of `example`

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output> {

loop {

match self { // TODO: handle pinning

ExampleStateMachine::Start(state) => {…}

ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnFooTxt(state) => {…}

ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnFooTxt(state) => {…}

ExampleStateMachine::End(state) => {…}

}

}

}

}

The Output type of the future is String because it's the return type of the example function. To implement the poll function, we use a match statement on the current state inside a loop. The idea is that we switch to the next state as long as possible and use an explicit return Poll::Pending when we can't continue.

For simplicity, we only show simplified code and don't handle pinning, ownership, lifetimes, etc. So this and the following code should be treated as pseudo-code and not used directly. Of course, the real compiler-generated code handles everything correctly, albeit possibly in a different way.

To keep the code excerpts small, we present the code for each match arm separately. Let's begin with the Start state:

ExampleStateMachine::Start(state) => {

// from body of `example`

let foo_txt_future = async_read_file("foo.txt");

// `.await` operation

let state = WaitingOnFooTxtState {

min_len: state.min_len,

foo_txt_future,

};

*self = ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnFooTxt(state);

}

The state machine is in the Start state when it is right at the beginning of the function. In this case, we execute all the code from the body of the example function until the first .await. To handle the .await operation, we change the state of the self state machine to WaitingOnFooTxt, which includes the construction of the WaitingOnFooTxtState struct.

Since the match self {…} statement is executed in a loop, the execution jumps to the WaitingOnFooTxt arm next:

ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnFooTxt(state) => {

match state.foo_txt_future.poll(cx) {

Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending,

Poll::Ready(content) => {

// from body of `example`

if content.len() < state.min_len {

let bar_txt_future = async_read_file("bar.txt");

// `.await` operation

let state = WaitingOnBarTxtState {

content,

bar_txt_future,

};

*self = ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnBarTxt(state);

} else {

*self = ExampleStateMachine::End(EndState));

return Poll::Ready(content);

}

}

}

}

In this match arm we first call the poll function of the foo_txt_future. If it is not ready, we exit the loop and return Poll::Pending. Since self stays in the WaitingOnFooTxt state in this case, the next poll call on the state machine will enter the same match arm and retry polling the foo_txt_future.

When the foo_txt_future is ready, we assign the result to the content variable and continue to execute the code of the example function: If content.len() is smaller than the min_len saved in the state struct, the bar.txt file is read asynchronously. We again translate the .await operation into a state change, this time into the WaitingOnBarTxt state. Since we're executing the match inside a loop, the execution directly jumps to the match arm for the new state afterwards, where the bar_txt_future is polled.

In case we enter the else branch, no further .await operation occurs. We reach the end of the function and return content wrapped in Poll::Ready. We also change the current state to the End state.

The code for the WaitingOnBarTxt state looks like this:

ExampleStateMachine::WaitingOnBarTxt(state) => {

match state.bar_txt_future.poll(cx) {

Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending,

Poll::Ready(bar_txt) => {

*self = ExampleStateMachine::End(EndState));

// from body of `example`

return Poll::Ready(state.content + &bar_txt);

}

}

}

Similar to the WaitingOnFooTxt state, we start by polling the bar_txt_future. If it is still pending, we exit the loop and return Poll::Pending. Otherwise, we can perform the last operation of the example function: Concatenating the content variable with the result from the future. We update the state machine to the End state and then return the result wrapped in Poll::Ready.

Finally, the code for the End state looks like this:

ExampleStateMachine::End(_) => {

panic!("poll called after Poll::Ready was returned");

}

Futures should not be polled again after they returned Poll::Ready, therefore we panic if poll is called when we are already in the End state.

We now know how the compiler-generated state machine and its implementation of the Future trait could look like. In practice, the compiler generates code in different way. (In case you're interested, the implementation is currently based on generators, but this is only an implementation detail.)

The last piece of the puzzle is the generated code for the example function itself. Remember, the function header was defined like this:

async fn example(min_len: usize) -> String

Since the complete function body is now implemented by the state machine, the only thing that the function needs to do is to initialize the state machine and return it. The generated code for this could look like this:

fn example(min_len: usize) -> ExampleStateMachine {

ExampleStateMachine::Start(StartState {

min_len,

})

}

The function no longer has an async modifier since it now explicitly returns a ExampleStateMachine type, which implements the Future trait. As expected, the state machine is constructed in the Start state and the corresponding state struct is initialized with the min_len parameter.

Note that this function does not start the execution of the state machine. This is a fundamental design decision of futures in Rust: They do nothing until they are polled for the first time.

Pinning

We already stumbled across pinning multiple times in this post. Now is finally the time to explore what pinning is and why it is needed.

Self-Referential Structs

As explained above, the state machine transformation stores the local variables of each pause point in a struct. For small examples like our example function, this was straightforward and did not lead to any problems. However, things become more difficult when variables reference each other. For example, consider this function:

async fn pin_example() -> i32 {

let array = [1, 2, 3];

let element = &array[2];

async_write_file("foo.txt", element.to_string()).await;

*element

}

This function creates a small array with the contents 1, 2, and 3. It then creates a reference to the last array element and stores it in an element variable. Next, it asynchronously writes the number converted to a string to a foo.txt file. Finally, it returns the number referenced by element.

Since the function uses a single await operation, the resulting state machine has three states: start, end, and "waiting on write". The function takes no arguments, so the struct for the start state is empty. Like before, the struct for the end state is empty too because the function is finished at this point. The struct for the "waiting on write" state is more interesting:

struct WaitingOnWriteState {

array: [1, 2, 3],

element: 0x1001a, // address of the last array element

}

We need to store both the array and element variables because element is required for the return type and array is referenced by element. Since element is a reference, it stores a pointer (i.e. a memory address) to the referenced element. We used 0x1001a as an example memory address here. In reality it needs to be the address of the last element of the array field, so it depends on where the struct lives in memory. Structs with such internal pointers are called self-referential structs because they reference themselves from one of their fields.

The Problem with Self-Referential Structs

The internal pointer of our self-referential struct leads to a fundamental problem, which becomes apparent when we look at its memory layout:

The array field starts at address 0x10014 and the element field at address 0x10020. It points to address 0x1001a because the last array element lives at this address. At this point, everything is still fine. However, an issue occurs when we move this struct to a different memory address:

We moved the struct a bit so that it starts at address 0x10024 now. This could for example happen when we pass the struct as a function argument or assign it to a different stack variable. The problem is that the element field still points to address 0x1001a even though the last array element now lives at address 0x1002a. Thus, the pointer is dangling with the result that undefined behavior occurs on the next poll call.

Possible Solutions

There are two fundamental approaches to solve the dangling pointer problem:

- Update the pointer on move: The idea is to update the internal pointer whenever the struct is moved in memory so that it is still valid after the move. Unfortunately, this approach would require extensive changes to Rust that would result in potentially huge performance losses. The reason is that some kind of runtime would need to keep track of the type of all struct fields and check on every move operation whether a pointer update is required.

- Forbid moving the struct: As we saw above, the dangling pointer only occurs when we move the struct in memory. By completely forbidding move operations on self-referential structs, the problem can be also avoided. The big advantage of this approach is that it can be implemented at the type system level without additional runtime costs. The drawback is that it puts the burden of dealing with move operations on possibly self-referential structs on the programmer.

Rust understandably decided for the second solution. For this, the pinning API was proposed in RFC 2349. In the following, we will give a short overview of this API and explain how it works with async/await and futures.

Heap Values

The first observation is that heap allocated values already have a fixed memory address most of the time. They are created using a call to allocate and then referenced by a pointer type such as Box<T>. While moving the pointer type is possible, the heap value that the pointer points to stays at the same memory address until it is freed through a deallocate call again.

Using heap allocation, we can try to create a self-referential struct:

fn main() {

let mut heap_value = Box::new(SelfReferential {

self_ptr: 0 as *const _,

});

let ptr = &*heap_value as *const SelfReferential;

heap_value.self_ptr = ptr;

println!("heap value at: {:p}", heap_value);

println!("internal reference: {:p}", heap_value.self_ptr);

}

struct SelfReferential {

self_ptr: *const Self,

}

We create a simple struct named SelfReferential that contains a single pointer field. First, we initialize this struct with a null pointer and then allocate it on the heap using Box::new. We then determine the memory address of the heap allocated struct and store it in a ptr variable. Finally, we make the struct self-referential by assigning the ptr variable to the self_ptr field.

When we execute this code on the playground, we see that the address of heap value and its internal pointer are equal, which means that the self_ptr field is a valid self-reference. Since the heap_value variable is only a pointer, moving it (e.g. by passing it to a function) does not change the address of the struct itself, so the self_ptr stays valid even if the pointer is moved.

However, there is still a way to break this example: We can move out of a Box<T> or replace its content:

let stack_value = mem::replace(&mut *heap_value, SelfReferential {

self_ptr: 0 as *const _,

});

println!("value at: {:p}", &stack_value);

println!("internal reference: {:p}", stack_value.self_ptr);

Here we use the mem::replace function to replace the heap allocated value with a new struct instance. This allows us to move the original heap_value to the stack, while the self_ptr field of the struct is now a dangling pointer that still points to the old heap address. When you try to run the example on the playground, you see that the printed "value at:" and "internal reference:" lines show indeed different pointers. So heap allpcating a value is not enough to make self-references safe.

The fundamental problem that allowed the above breakage is that Box<T> allows us to get a &mut T reference to the heap allocated value. This &mut reference makes it possible to use methods like mem::replace or mem::swap to invalidate the heap allocated value. To resolve this problem, we must prevent that &mut references to self-referential structs can be created.

Pin<Box<T>> and Unpin

The pinning API provides a solution to the &mut T problem in form of the Pin wrapper type and the Unpin marker trait. The idea behind these types is to gate all methods of Pin that can be used to get &mut references to the wrapped value (e.g. get_mut or deref_mut) on the Unpin trait. The Unpin trait is an auto trait, which is automatically implemented for all types except types that explicitly opt-out. By making self-referential structs opt-out of Unpin, there is no (safe) way to get a &mut T from a Pin<Box<T>> type for them. As a result, their internal self-references are guaranteed to stay valid.

As an example, let's update the SelfReferential type from above to opt-out of Unpin:

use core::marker::PhantomPinned;

struct SelfReferential {

self_ptr: *const Self,

_pin: PhantomPinned,

}

We opt-out by adding a second _pin field of type PhantomPinned. This type is a zero-sized marker type whose only purpose is to not implement the Unpin trait. Because of the way auto traits work, a single field that is not Unpin suffices to make the complete struct opt-out of Unpin.

The second step is to change the Box<SelfReferential> type in the example to a Pin<Box<SelfReferential>> type. The easiest way to do this is to use the Box::pin function instead of Box::new for creating the heap allocated value:

let mut heap_value = Box::pin(SelfReferential {

self_ptr: 0 as *const _,

_pin: PhantomPinned,

});

In addition to changing Box::new to Box::pin, we also need to add the new _pin field in the struct initializer. Since PhantomPinned is a zero sized type, we only need its type name to initialize it.

When we try to run our adjusted example now, we see that it no longer works:

error[E0594]: cannot assign to data in a dereference of `std::pin::Pin<std::boxed::Box<SelfReferential>>`

--> src/main.rs:10:5

|

10 | heap_value.self_ptr = ptr;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ cannot assign

|

= help: trait `DerefMut` is required to modify through a dereference, but it is not implemented for `std::pin::Pin<std::boxed::Box<SelfReferential>>`

error[E0596]: cannot borrow data in a dereference of `std::pin::Pin<std::boxed::Box<SelfReferential>>` as mutable

--> src/main.rs:16:36

|

16 | let stack_value = mem::replace(&mut *heap_value, SelfReferential {

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ cannot borrow as mutable

|

= help: trait `DerefMut` is required to modify through a dereference, but it is not implemented for `std::pin::Pin<std::boxed::Box<SelfReferential>>`

Both errors occur because the Pin<Box<SelfReferential>> type no longer implements the DerefMut trait. This exactly what we wanted because the DerefMut trait would return a &mut reference, which we want to prevent. This only happens because we both opted-out of Unpin and changed Box::new to Box::pin.

The problem now is that the compiler does not only prevent moving the type in line 16, but also forbids to initialize the self_ptr field in line 10. This happens because the compiler can't differentiate between valid and invalid uses of &mut references. To get the initialization working again, we have to use the unsafe get_unchecked_mut method:

// safe because modifying a field doesn't move the whole struct

unsafe {

let mut_ref = Pin::as_mut(&mut heap_value);

Pin::get_unchecked_mut(mut_ref).self_ptr = ptr;

}

The get_unchecked_mut function works on a Pin<&mut T> instead of a Pin<Box<T>>, so we have to use the Pin::as_mut for converting the value before. Then we can set the self_ptr field using the &mut reference returned by get_unchecked_mut.

Now the only error left is the desired error on mem::replace. Remember, this operation tries to move the heap allocated value to stack, which would break the self-reference stored in the self_ptr field. By opting out of Unpin and using Pin<Box<T>>, we can prevent this error and safely work with self-referential structs. Note that the compiler is not able to prove that the creation of the self-reference is safe (yet), so we need to use an unsafe block and verify the correctness ourselves.

Stack Pinning and Pin<&mut T>

In the previous section we learned how to use Pin<Box<T>> to safely create a heap allocated self-referential value. While this approach works fine and is relatively safe (apart from the unsafe construction), the required heap allocation comes with a performance cost. Since Rust always wants to provide zero-cost abstractions when possible, the pinning API also allows to create Pin<&mut T> instances that point to stack allocated values.

Unlike Pin<Box<T>> instances, which have ownership of the wrapped value, Pin<&mut T> instances only temporarily borrow the wrapped value. This makes things more compilicated, as it requires the programmer to ensure additional guarantees themself. Most importantly, a Pin<&mut T> must stay pinned for the whole lifetime of the referenced T, which can be difficult to verify for stack based variables. To help with this, crates like pin-utils exist, but I still wouldn't recommend pinning to the stack unless you really know what you're doing.

For further reading, check out the documentation of the pin module and the Pin::new_unchecked method.

Pinning and Futures

As we already saw in this post, the Future::poll method uses pinning in form of a Pin<&mut Self> parameter:

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output>

The reason that this method takes self: Pin<&mut Self> instead of the normal &mut self is that future instances created from async/await are often self-referential, as we saw above. By wrapping Self into Pin and letting the compiler opt-out of Unpin for self-referentual futures generated from async/await, it is guaranteed that the futures are not moved in memory between poll calls. This ensures that all internal references are still valid.

It is worth noting that moving futures before the first poll call is fine. This is a result of the fact that futures are lazy and do nothing until they're polled for the first time. The start state of the generated state machines therefore only contains the function arguments, but no internal references. In order to call poll, the caller must wrap the future into Pin first, which ensures that the future cannot be moved in memory anymore. Since stack pinning is more difficult to get right, I recommend to always use Box::pin combined with Pin::as_mut for this.

In case you're interested in understanding how to safely implement a future combinator function using stack pinning yourself, take a look at the relatively short source of the map combinator method of the futures crate and the section about projections and structural pinning of the pin documentation.

Executors and Wakers

Using async/await, it is possible to ergonomically work with futures in a completely asynchronous way. However, as we learned above, futures do nothing until they are polled. This means we have to have to call poll on them at some point, otherwise the asynchronous code is never executed.

With a single future, we can always wait for the future using a loop as described above. However, this approach is very inefficient, especially for programs that create a large number of futures. An example for such a program could be a web server that handles each request using an asynchronous function:

async fn handle_request(request: Request) {…}

The function is invoked for each request the webserver receives. It has no return type, so it results in a future with the empty type () as output. When the web server receives many concurrent requests, this can easily result in hundreds or thousands of futures in the system. While these futures have no return value that we need for future computations, we still want them to be polled to completion because otherwise the requests would not be handled.

The most common approach for this is to define a global executor that is responsible for polling all futures in the system until they are finished.

Executors

The purpose of an executor is to allow spawning futures as independent tasks, typically through some sort of spawn method. The executor is then responsible for polling all futures until they are completed. The big advantage of managing all futures in a central place is that the executor can switch to a different future whenever a future returns Poll::Pending. Thus, asynchronous operations are run in parallel and the CPU is kept busy.

Many executor implementations can also take advantage of systems with multiple CPU cores. They create a thread pool that is able to utilize all cores if there is enough work available and use techniques such as work stealing to balance the load between cores. There are also special executor implementations for embedded systems that optimize for low latency and memory overhead.

To avoid the overhead of polling futures over and over again, executors typically also take advantage of the waker API supported by Rust's futures.

Wakers

The idea behind the waker API is that a special Waker type is passed to each invocation of poll, wrapped in a Context type for future extensibility. This Waker type is created by the executor and can be used by the asynchronous task to signal its (partial) completion. As a result, the executor does not need to call poll on a future that previously returned Poll::Pending again until it is notified by the corresponding waker.

This is best illustrated by a small example:

async fn write_file() {

async_write_file("foo.txt", "Hello").await;

}

This function asynchronously writes the string "Hello" to a foo.txt file. Since hard disk writes take some time, the first poll call on this future will likely return Poll::Pending. However, the hard disk driver will internally store the Waker passed in the poll call and signal it as soon as the file was written to disk. This way, the executor does not need to waste any time trying to poll the future again before it receives the waker notification.

We will see how the Waker type works in detail when we create our own executor with waker support in the implementation section of this post.

Cooperative Multitasking?

At the beginning of this post we talked about preemptive and cooperative multitasking. While preemptive multitasking relies on the operating system to forcibly switch between running tasks, cooperative multitasking requires that the tasks voluntarily give up control of the CPU through a yield operation on a regular basis. The big advantage of the cooperative approach is that tasks can save their state themselves, which results in more efficient context switches and makes it possible to share the same call stack between tasks.

It might not be immediately apparent, but futures and async/await are an implementation of the cooperative multitasking pattern:

- Each future that is added to the executor is basically an cooperative task.

- Instead of using an explicit yield operation, futures give up control of the CPU core by returning

Poll::Pending(orPoll::Readyat the end).- There is nothing that forces futures to give up the CPU. If they want, they can never return from

poll, e.g. by spinning endlessly in a loop. - Since each future can block the execution of the other futures in the executor, we need to trust they are not malicious.

- There is nothing that forces futures to give up the CPU. If they want, they can never return from

- Futures internally store all the state they need to continue execution on the next

pollcall. With async/await, the compiler automatically detects all variables that are needed and stores them inside the generated state machine.- Only the minimum state required for continuation is saved.

- Since the

pollmethod gives up the call stack when it returns, the same stack can be used for polling other futures.

We see that futures and async/await fit the cooperative multitasking pattern perfectly, they just use some different terminology. In the following, we will therefore use the terms "task" and "future" interchangeably.

Implementation

Now that we understand how cooperative multitasking based on futures and async/await works in Rust, it's time to add support for it to our kernel. Since the Future trait is part of the core library and async/await is a feature of the language itself, there is nothing special we need to do to use it in our #![no_std] kernel. The only requirement is that we use at least nightly-TODO of Rust because async/await was not no_std compatible before.

With a recent-enough nightly, we can start using async/await in our main.rs:

// in src/main.rs

async fn async_number() -> u32 {

42

}

async fn example_task() {

let number = async_number().await;

println!("async number: {}", number);

}

The async_number function is an async fn, so the compiler transforms it into a state machine that implements Future. Since the function only returns 42, the resulting future will directly return Poll::Ready(42) on the first poll call. Like async_number, the example_task function is also an async fn. It awaits the number returned by async_number and then prints it using the println macro.

To run the future returned by example_task, we need to call poll on it until it signals its completion by returning Poll::Ready. To do this, we need to create a simple executor type.

Task

Before we start the executor implementation, we create a new task module with a Task type:

// in src/lib.rs

pub mod task;

// in src/task/mod.rs

use core::{future::Future, pin::Pin};

use alloc::boxed::Box;

pub struct Task {

future: Pin<Box<dyn Future<Output = ()>>>,

}

The Task struct is a newtype wrapper around a pinned, heap allocated, dynamically dispatched future with the empty type () as output. Let's go through it in detail:

- We require that the future associated with a task returns

(). This means that tasks don't return any result, they are just executed for its side effects. For example, theexample_taskfunction we defined above has no return value, but it prints something to the screen as a side effect. - The

dynkeyword indicates that we store a trait object in theBox. This means that the type of the future is dynamically dispatched, which makes it possible to store different types of futures in theTasktype. This is important because eachasync fnhas their own type and we want to be able to create different tasks later. - As we learned in the section about pinning, the

Pin<Box>type ensures that a value cannot be moved in memory by placing it on the heap and preventing the creation of&mutreferences to it. This is important because futures generated by async/await might be self-referential, i.e. contain pointers to itself that would be invalidated when the future is moved.

To allow the creation of new Task structs from futures, we create a new function:

// in src/task/mod.rs

impl Task {

pub fn new(future: impl Future<Output = ()> + 'static) -> Task {

Task {

future: Box::pin(future),

}

}

}

The function takes an arbitrary future with output type () and pins it in memory through the Box::pin function. Then it wraps it in the Task struct and returns the new task. The 'static lifetime is required here because the returned Task can live for an arbitrary time, so the future needs to be valid for that time too.

We also add a poll method to allow the executor to poll the corresponding future:

// in src/task/mod.rs

use core::task::{Context, Poll};

impl Task {

fn poll(&mut self, context: &mut Context) -> Poll<()> {

self.future.as_mut().poll(context)

}

}

Since the poll method of the Future trait expects to be called on a Pin<&mut T> type, we use the Pin::as_mut method to convert the self.future field of type Pin<Box<T>> first. Then we call poll on the converted self.future field and return the result. Since the Task::poll method should be only called by the executor that we create in a moment, we keep the function private to the task module.

Simple Executor

Since executors can be quite complex, we deliberately start with creating a very basic executor before we implement a more featureful executor later. For this, we first create a new task::simple_executor submodule:

// in src/task/mod.rs

pub mod simple_executor;

// in src/task/simple_executor.rs

use super::Task;

use alloc::collections::VecDeque;

pub struct SimpleExecutor {

task_queue: VecDeque<Task>,

}

impl SimpleExecutor {

pub fn new() -> SimpleExecutor {

SimpleExecutor {

task_queue: VecDeque::new(),

}

}

pub fn spawn(&mut self, task: Task) {

self.task_queue.push_back(task)

}

}

The struct contains a single task_queue field of type VecDeque, which is basically a vector that allows to push and pop on both ends. The idea behind using this type is that we insert new tasks through the spawn method at the end and pop the next task for execution from the front. This way, we get a simple FIFO queue ("first in, first out").

Dummy Waker

In order to call the poll method, we need to create a Context type, which wraps a Waker type. To start simple, we will first create a dummy waker that does nothing. The simplest way to do this is by implementing the unstable Wake trait for an empty DummyWaker struct:

// in src/task/simple_executor.rs

use alloc::{sync::Arc, task::Wake};

struct DummyWaker;

impl Wake for DummyWaker {

fn wake(self: Arc<Self>) {

// do nothing

}

}

The trait is still unstable, so we have to add #![feature(wake_trait)] to the top of our lib.rs to use it. The wake method of the trait is normally responsible for waking the corresponding task in the executor. However, our SimpleExecutor will not differentiate between ready and waiting tasks, so we don't need to do anything on wake calls.

Since wakers are normally shared between the executor and the asynchronous tasks, the wake method requires that the Self instance is wrapped in the Arc type, which implements reference-counted ownership. The basic idea is that the value is heap-allocated and the number of active references to it are counted. If the number of active references reaches zero, the value is no longer needed and can be deallocated.

To make our DummyWaker usable with the Context type, we need a method to convert it to the Waker defined in the core library:

// in src/task/simple_executor.rs

use core::task::Waker;

impl DummyWaker {

fn to_waker(self) -> Waker {

Waker::from(Arc::new(self))

}

}

The method first makes the self instance reference-counted by wrapping it in an Arc. Then it uses the Waker::from method to create the Waker. This method is available for all reference counted types that implement the Wake trait.

Now we have a way to create a Waker instance, we can use it to implement a run method on our executor.

A run Method

The most simple run method is to repeatedly poll all queued tasks in a loop until all are done. This is not very efficient since it does not utilize the notifications of the Waker type, but it is an easy way to get things running:

// in src/task/simple_executor.rs

use core::task::{Context, Poll};

impl SimpleExecutor {

pub fn run(&mut self) {

while let Some(mut task) = self.task_queue.pop_front() {

let waker = DummyWaker.to_waker();

let mut context = Context::from_waker(&waker);

match task.poll(&mut context) {

Poll::Ready(()) => {} // task done

Poll::Pending => self.task_queue.push_back(task),

}

}

}

}

The function uses a while let loop to handle all tasks in the task_queue. For each task, it first creates a Context type by wrapping a Waker instance created from our DummyWaker type. Then it invokes the Task::poll method with this Context. If the poll method returns Poll::Ready, the task is finished and we can continue with the next task. If the task is still Poll::Pending, we add it to the back of the queue again so that it will be polled again in a subsequent loop iteration.

Trying It

With our SimpleExecutor type, we can now try running the task returned by the example_task function in our main.rs:

// in src/main.rs

use blog_os::task::{Task, simple_executor::SimpleExecutor};

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// […] initialization routines, including `init_heap`

let mut executor = SimpleExecutor::new();

executor.spawn(Task::new(example_task()));

executor.run();

// […] test_main, "it did not crash" message, hlt_loop

}

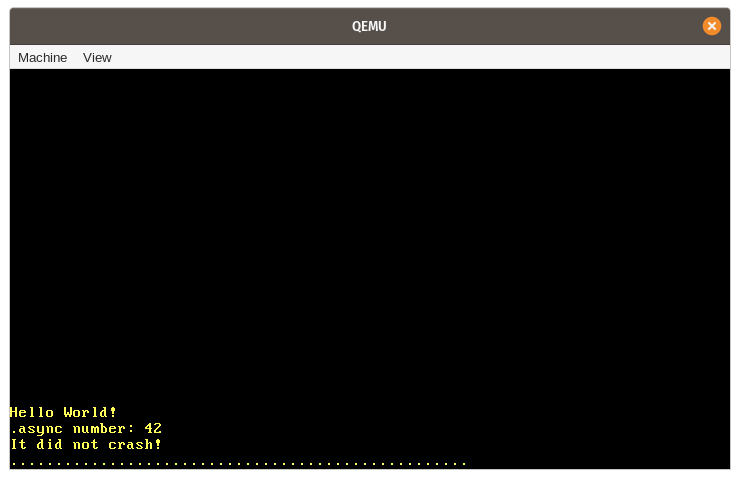

When we run it, we see that the expected "async number: 42" message is printed to the screen:

Let's summarize the various steps that happen for this example:

- First, a new instance of our

SimpleExecutortype is created with an emptytask_queue. - Next, we call the asynchronous

example_taskfunction, which returns a future. We wrap this future in theTasktype, which moves it to the heap and pins it, and then add the task to thetask_queueof the executor through thespawnmethod. - We then wall the

runmethod to start the execution of the single task in the queue. This involves:- Popping the task from the front of the

task_queue. - Creating a

DummyWakerfor the task, converting it to aWakerinstance, and then creating aContextinstance from it. - Calling the

pollmethod on the future of the task, using theContextwe just created. - Since the

example_taskdoes not wait for anything, it can directly run til its end on the firstpollcall. This is where the "async number: 42" line is printed. - Since the

example_taskdirectly returnsPoll::Ready, it is not added back to the task queue.

- Popping the task from the front of the

- The

runmethod returns after thetask_queuebecomes empty. The execution of ourkernel_mainfunction continues and the "It did not crash!" message is printed.

Async Keyboard Input

Our simple executor does not utilize the Waker notifications and simply loops over all tasks until they are done. This wasn't a problem for our example since our example_task can directly run to finish on the first poll call. To see the performance advantages of a proper Waker implementation, we first need to create a task that is truly asynchronous, i.e. a task that will probably return Poll::Pending on the first poll call.

We already have some kind of asynchronicity in our system that we can use for this: hardware interrupts. As we learned in the Interrupts post, hardware interrupts can occur at arbitrary points in time, determined by some external device. For example, a hardware timer sends an interrupt to the CPU after some predefined time elapsed. When the CPU receives an interrupt, it immediately transfers control to the corresponding handler function defined in the interrupt descriptor table (IDT).

In the following, we will create an asynchronous task based on the keyboard interrupt. The keyboard interrupt is a good candidate for this because it is both non-deterministic and latency-critical. Non-deteministic means that there is no way to predict when the next key press will occur because it is entirely dependent on the user. Latency-critical means that we want to handle the keyboard input in a timely manner, otherwise the user will feel a lag. To support such a task in an efficient way, it will be essential that the executor has proper support for Waker notifications.

Scancode Queue

Currently, we handle the keyboard input directly in the interrupt handler. This is not a good idea for the long term because interrupt handlers should stay as short as possible as they might interrupt important work. Instead, interrupt handlers should only perform the minimal amount of work necessary (e.g. reading the keyboard scancode) and leave the rest of the work (e.g. interpreting the scancode) to a background task.

A common pattern for delegating work to a background task is to create some sort of queue. The interrupt handler pushes work units of work to the queue and the background task handles the work in the queue. Applied to our keyboard interrupt, this means that the interrupt handler only reads the scancode from the keyboard, pushes it to the queue, and then returns. The keyboard task sits on the other end of the queue and interprets and handles each scancode that is pushed to it:

A simple implementation of that queue could be a mutex-protected VecDeque. However, using mutexes in interrupt handlers is not a good idea since it can easily lead to deadlocks. For example, when the user presses a key while the keyboard task has locked the queue, the interrupt handler tries to acquire the lock again and hangs indefinitely. Another problem with this approach is that VecDeque automatically increases its capacity by performing a new heap allocation when it becomes full. This can lead to deadlocks again because our allocator also uses a mutex internally. Further problems are that heap allocations can fail or take a considerable amount of time when the heap is fragmented.

To prevent these problems, we need a queue implementation that does not require mutexes or allocations for its push operation. Such queues can be implemented by using lock-free atomic operations for pushing and popping elements. This way, it is possible to create push and pop operations that only require a &self reference and are thus usable without a mutex. To avoid allocations on push, the queue can be backed by a pre-allocated fixed-size buffer. While this makes the queue bounded (i.e. it has a maximum length), it is often possible to define reasonable upper bounds for the queue length in practice so that this isn't a big problem.

Crossbeam

Implementing such a queue in a correct and efficient way is very difficult, so I recommend to stick to existing, well-tested implementations. One popular Rust project that implements various mutex-free types for concurrent programming is crossbeam. It provides a type named ArrayQueue that is exactly what we need in this case. And we're lucky: The type is fully compatible to no_std crates with allocation support.

To use the type, we need to add a dependency on the crossbeam-queue crate:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies.crossbeam-queue]

version = "0.2.1"

default-features = false

features = ["alloc"]

By default, the crate depends on the standard library. To make it no_std compatible, we need to disable its default features and instead enable the alloc feature. (Note that depending on the main crossbeam crate does not work here because it is missing an export of the queue module for no_std. I filed a pull request to fix this.)

Implementation

Using the ArrayQueue type, we can now create a global scancode queue in a new task::keyboard module:

// in src/task/mod.rs

pub mod keyboard;

// in src/task/keyboard.rs

use conquer_once::spin::OnceCell;

use crossbeam_queue::ArrayQueue;

static SCANCODE_QUEUE: OnceCell<ArrayQueue<u8>> = OnceCell::uninit();

Since the ArrayQueue::new performs a heap allocation, which are not possible at compile time (yet), we can't initialize the static variable directly. Instead, we use the OnceCell type of the conquer_once crate, which makes it possible to perform safe one-time initialization of static values. To include the crate, we need to add it as a dependency in our Cargo.toml:

# in Cargo.toml

[dependencies.conquer-once]

version = "0.2.0"

default-features = false

Instead of the OnceCell primitive, we could also use the lazy_static macro here. However, the OnceCell type has the advantage that we can ensure that the initialization does not happen in the interrupt handler, thus preventing that the interrupt handler performs a heap allocation.