34 KiB

+++ title = "Un noyau Rust minimal" weight = 2 path = "fr/minimal-rust-kernel" date = 2018-02-10

[extra] chapter = "Bare Bones"

Please update this when updating the translation

translation_based_on_commit = "c689ecf810f8e93f6b2fb3c4e1e8b89b8a0998eb"

GitHub usernames of the people that translated this post

translators = ["TheMimiCodes", "maximevaillancourt"] +++

Dans cet article, nous créons un noyau Rust minimal 64-bit pour l'architecture x86. Nous continuons le travail fait dans l'article précédent freestanding Rust binary pour créer une image de disque amorçable qui imprime quelque chose à l'écran.

Cet article est développé ouvertement sur GitHub. Si vous avez des problèmes ou des questions, veuillez ouvrir une Issue sur GitHub. Vous pouvez aussi laisser un commentaire au bas de la page. Le code source complet pour cet article peut être trouvé dans la branche post-02.

The Boot Process

QUand vous ouvrez un ordinateur, il commence à exécuter le code du micrologiciel qui est enregistré dans la carte maîtresseROM. Ce code performe un power-on self-test, détecte la mémoire volatile disponible, et pré-initialise le CPU et le matériel. Par la suite, il recherche un disque amorçable et commence le processus d'amorçage du noyau du système d'exploitation.

Sur x86, il y a deux standards pour les micrologiciels: le “Basic Input/Output System“ (BIOS) et le nouvel “Unified Extensible Firmware Interface” (UEFI). Le BIOS standard est vieux et dépassé, mais il est simple et bien suporté sur toutes les machines x86 depuis les années 1980. Au contraire, l'UEFI, est plutôt moderne et il offre davantage de fonctionnalités, cependant, il est plus complexe à installer (du moins, selon moi).

Actuellement, nous offrons seulement un support BIOS, mais nous planifions aussi du support pour l'UEFI. Si vous aimeriez nous aider avec cela, consultez Github issue.

BIOS Boot

Presque tous les systèmes x86 ont des support pour amorcer le BIOS, incluant les récentes machine UEFI-based qui utilisent un BIOS émulé. C'est bien étant donné que vous pouvez utiliser la même logique d'armorçage sur toutes les machines du dernier siècle. De plus, cette grande compatibilité est à la fois le plus grand désavantage de l'amorçage BIOS. En effet, cela signifie que le CPU est mis dans un mode de compatibilité 16-bit appelé real mode avant l'amorçage afin que les bootloaders archaïques des années 1980 puissent encore fonctionner.

Commençons par le commencement:

Quand vous ouvrez votre ordinateur, il charge le BIOS provenant d'un emplacement de mémoire flash spéciale localisée sur la carte maîtresse. Le BIOS exécute des tests d'auto-diagnostic et es routines d'initialisation du matériel, puis il cherche des disques amorçables. S'il en trouve un, le contrôle est transféré à its bootloader, qui est une portion 512-byte du code exécutable enregistré au début du disque. La pluplart des bootloaders sont plus gros que 512 bytes, alors les bootloaders sont communément séparés en deux étapes. La première étape, est de 512 bytes, et la seconde étape, est chargé subséquemment à la première étapge.

Le bootloader doit déterminé la localisation de l'image de noyau sur le disque et de la télécharger dans sa mémoire. Il doit aussi transformer le CPU 16-bit real mode en un 32-bit protected mode, puis en un 64-bit long mode, où les registres 64-bit et la mémoire maîtresse complète sont disponibles. Sa troisième tâche est de récupérer certaines informations (telle que les associations mémoires) du BIOS et les passer au noyau du système d'exploitation.

Implémenter un bootloader est délicat puisque cela requiert l'écriture de code assembleur et plusieurs autres étapes particulières comme “write this magic value to this processor register”. Par conséquent, nous ne couvrons pas la création d'un bootoader dans cet article et nous fournissons plutôt un outil appelé bootimage qui ajoute automatiquement un bootloader à votre noyau.

Si vous êtes intéressé à créer votre propre booloader : Gardez l'oeil ouvert, plusieurs articles sur ce sujet sont déjà prévus!

The Multiboot Standard

Pour éviter que chaque système d'opération implémente son propre bootloader, qui est seulement compatible avec un seul système d'exploitation, le Free Software Foundation à créé un bootloader public standard appelé Multiboot en 1995. Le standard défini une interface entre le bootloader et le système d'opération afin que n'importe quel Multiboot-compliant bootloader puisse charger n'importe quel système d'opérations Multiboot-compliant. La référence d'implementation est GNU GRUB, qui est le bootloader le plus populaire pour les systèmes Linux.

Pour faire un noyau conforme à la spécification Multiboot, il faut seulement inséré un Multiboot header au début du fichier du noyau. Cela fait en sorte que c'est très simple to boot un système d'exploitation depuis GRUB. Cependant, le GRUB et le Multiboot standard présentent aussi des problèmes :

- Ils supportent seulement le mode de protection 32-bit. Cela signifie que si vous devez encore faire la configuration du CPU pour changer au 64-bit long mode.

- Ils sont désignés pour faire le bootloader simple plutôt que le noyau. Par exemple, le noyau doit être lié avec un adjusted default page size, étant donné que le GRUB ne peut pas trouver les entêtes Multiboot autrement. Un autre exemple est que le boot information, qui est passé au noyau, contient plusieurs structures spécifiques à l'architecture plutôt que de fournir des abstractions pures.

- GRUB et le standard Multiboot sont peu documentés.

- GRUB doit être installé sur un système hôte pour créer une image de disque amorçable depuis le fichier du noyau. Cela rend le développement sur Windows ou sur Mac plus difficile.

Because of these drawbacks, nous avons décidé de ne pas utiliser GRUB ou le standard Multiboot. Cependant, nous avons planifié d'ajouter un support Multiboot à notre outil bootimage, afin qu'il soit aussi possible de charger votre noyau sur un système GRUB. Si vous êtes interessé à écrire un noyau Multiboot conforme, consultez la first edition de cette série d'articles.

UEFI

(We don't provide UEFI support at the moment, but we would love to! If you'd like to help, please tell us in the Github issue.)

A Minimal Kernel

Now that we roughly know how a computer boots, it's time to create our own minimal kernel. Our goal is to create a disk image that prints a “Hello World!” to the screen when booted. We do this by extending the previous post's freestanding Rust binary.

As you may remember, we built the freestanding binary through cargo, but depending on the operating system, we needed different entry point names and compile flags. That's because cargo builds for the host system by default, i.e., the system you're running on. This isn't something we want for our kernel, because a kernel that runs on top of, e.g., Windows, does not make much sense. Instead, we want to compile for a clearly defined target system.

Installing Rust Nightly

Rust has three release channels: stable, beta, and nightly. The Rust Book explains the difference between these channels really well, so take a minute and check it out. For building an operating system, we will need some experimental features that are only available on the nightly channel, so we need to install a nightly version of Rust.

To manage Rust installations, I highly recommend rustup. It allows you to install nightly, beta, and stable compilers side-by-side and makes it easy to update them. With rustup, you can use a nightly compiler for the current directory by running rustup override set nightly. Alternatively, you can add a file called rust-toolchain with the content nightly to the project's root directory. You can check that you have a nightly version installed by running rustc --version: The version number should contain -nightly at the end.

The nightly compiler allows us to opt-in to various experimental features by using so-called feature flags at the top of our file. For example, we could enable the experimental asm! macro for inline assembly by adding #![feature(asm)] to the top of our main.rs. Note that such experimental features are completely unstable, which means that future Rust versions might change or remove them without prior warning. For this reason, we will only use them if absolutely necessary.

Target Specification

Cargo supports different target systems through the --target parameter. The target is described by a so-called target triple, which describes the CPU architecture, the vendor, the operating system, and the ABI. For example, the x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu target triple describes a system with an x86_64 CPU, no clear vendor, and a Linux operating system with the GNU ABI. Rust supports many different target triples, including arm-linux-androideabi for Android or wasm32-unknown-unknown for WebAssembly.

For our target system, however, we require some special configuration parameters (e.g. no underlying OS), so none of the existing target triples fits. Fortunately, Rust allows us to define our own target through a JSON file. For example, a JSON file that describes the x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu target looks like this:

{

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu",

"data-layout": "e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

"arch": "x86_64",

"target-endian": "little",

"target-pointer-width": "64",

"target-c-int-width": "32",

"os": "linux",

"executables": true,

"linker-flavor": "gcc",

"pre-link-args": ["-m64"],

"morestack": false

}

Most fields are required by LLVM to generate code for that platform. For example, the data-layout field defines the size of various integer, floating point, and pointer types. Then there are fields that Rust uses for conditional compilation, such as target-pointer-width. The third kind of field defines how the crate should be built. For example, the pre-link-args field specifies arguments passed to the linker.

We also target x86_64 systems with our kernel, so our target specification will look very similar to the one above. Let's start by creating an x86_64-blog_os.json file (choose any name you like) with the common content:

{

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-none",

"data-layout": "e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

"arch": "x86_64",

"target-endian": "little",

"target-pointer-width": "64",

"target-c-int-width": "32",

"os": "none",

"executables": true

}

Note that we changed the OS in the llvm-target and the os field to none, because we will run on bare metal.

We add the following build-related entries:

"linker-flavor": "ld.lld",

"linker": "rust-lld",

Instead of using the platform's default linker (which might not support Linux targets), we use the cross-platform LLD linker that is shipped with Rust for linking our kernel.

"panic-strategy": "abort",

This setting specifies that the target doesn't support stack unwinding on panic, so instead the program should abort directly. This has the same effect as the panic = "abort" option in our Cargo.toml, so we can remove it from there. (Note that, in contrast to the Cargo.toml option, this target option also applies when we recompile the core library later in this post. So, even if you prefer to keep the Cargo.toml option, make sure to include this option.)

"disable-redzone": true,

We're writing a kernel, so we'll need to handle interrupts at some point. To do that safely, we have to disable a certain stack pointer optimization called the “red zone”, because it would cause stack corruption otherwise. For more information, see our separate post about disabling the red zone.

"features": "-mmx,-sse,+soft-float",

The features field enables/disables target features. We disable the mmx and sse features by prefixing them with a minus and enable the soft-float feature by prefixing it with a plus. Note that there must be no spaces between different flags, otherwise LLVM fails to interpret the features string.

The mmx and sse features determine support for Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions, which can often speed up programs significantly. However, using the large SIMD registers in OS kernels leads to performance problems. The reason is that the kernel needs to restore all registers to their original state before continuing an interrupted program. This means that the kernel has to save the complete SIMD state to main memory on each system call or hardware interrupt. Since the SIMD state is very large (512–1600 bytes) and interrupts can occur very often, these additional save/restore operations considerably harm performance. To avoid this, we disable SIMD for our kernel (not for applications running on top!).

A problem with disabling SIMD is that floating point operations on x86_64 require SIMD registers by default. To solve this problem, we add the soft-float feature, which emulates all floating point operations through software functions based on normal integers.

For more information, see our post on disabling SIMD.

Putting it Together

Our target specification file now looks like this:

{

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-none",

"data-layout": "e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

"arch": "x86_64",

"target-endian": "little",

"target-pointer-width": "64",

"target-c-int-width": "32",

"os": "none",

"executables": true,

"linker-flavor": "ld.lld",

"linker": "rust-lld",

"panic-strategy": "abort",

"disable-redzone": true,

"features": "-mmx,-sse,+soft-float"

}

Building our Kernel

Compiling for our new target will use Linux conventions (I'm not quite sure why; I assume it's just LLVM's default). This means that we need an entry point named _start as described in the previous post:

// src/main.rs

#![no_std] // don't link the Rust standard library

#![no_main] // disable all Rust-level entry points

use core::panic::PanicInfo;

/// This function is called on panic.

#[panic_handler]

fn panic(_info: &PanicInfo) -> ! {

loop {}

}

#[no_mangle] // don't mangle the name of this function

pub extern "C" fn _start() -> ! {

// this function is the entry point, since the linker looks for a function

// named `_start` by default

loop {}

}

Note that the entry point needs to be called _start regardless of your host OS.

We can now build the kernel for our new target by passing the name of the JSON file as --target:

> cargo build --target x86_64-blog_os.json

error[E0463]: can't find crate for `core`

It fails! The error tells us that the Rust compiler no longer finds the core library. This library contains basic Rust types such as Result, Option, and iterators, and is implicitly linked to all no_std crates.

The problem is that the core library is distributed together with the Rust compiler as a precompiled library. So it is only valid for supported host triples (e.g., x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu) but not for our custom target. If we want to compile code for other targets, we need to recompile core for these targets first.

The build-std Option

That's where the build-std feature of cargo comes in. It allows to recompile core and other standard library crates on demand, instead of using the precompiled versions shipped with the Rust installation. This feature is very new and still not finished, so it is marked as "unstable" and only available on nightly Rust compilers.

To use the feature, we need to create a cargo configuration file at .cargo/config.toml with the following content:

# in .cargo/config.toml

[unstable]

build-std = ["core", "compiler_builtins"]

This tells cargo that it should recompile the core and compiler_builtins libraries. The latter is required because it is a dependency of core. In order to recompile these libraries, cargo needs access to the rust source code, which we can install with rustup component add rust-src.

Note: The unstable.build-std configuration key requires at least the Rust nightly from 2020-07-15.

After setting the unstable.build-std configuration key and installing the rust-src component, we can rerun our build command:

> cargo build --target x86_64-blog_os.json

Compiling core v0.0.0 (/…/rust/src/libcore)

Compiling rustc-std-workspace-core v1.99.0 (/…/rust/src/tools/rustc-std-workspace-core)

Compiling compiler_builtins v0.1.32

Compiling blog_os v0.1.0 (/…/blog_os)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.29 secs

We see that cargo build now recompiles the core, rustc-std-workspace-core (a dependency of compiler_builtins), and compiler_builtins libraries for our custom target.

Memory-Related Intrinsics

The Rust compiler assumes that a certain set of built-in functions is available for all systems. Most of these functions are provided by the compiler_builtins crate that we just recompiled. However, there are some memory-related functions in that crate that are not enabled by default because they are normally provided by the C library on the system. These functions include memset, which sets all bytes in a memory block to a given value, memcpy, which copies one memory block to another, and memcmp, which compares two memory blocks. While we didn't need any of these functions to compile our kernel right now, they will be required as soon as we add some more code to it (e.g. when copying structs around).

Since we can't link to the C library of the operating system, we need an alternative way to provide these functions to the compiler. One possible approach for this could be to implement our own memset etc. functions and apply the #[no_mangle] attribute to them (to avoid the automatic renaming during compilation). However, this is dangerous since the slightest mistake in the implementation of these functions could lead to undefined behavior. For example, implementing memcpy with a for loop may result in an infinite recursion because for loops implicitly call the IntoIterator::into_iter trait method, which may call memcpy again. So it's a good idea to reuse existing, well-tested implementations instead.

Fortunately, the compiler_builtins crate already contains implementations for all the needed functions, they are just disabled by default to not collide with the implementations from the C library. We can enable them by setting cargo's build-std-features flag to ["compiler-builtins-mem"]. Like the build-std flag, this flag can be either passed on the command line as a -Z flag or configured in the unstable table in the .cargo/config.toml file. Since we always want to build with this flag, the config file option makes more sense for us:

# in .cargo/config.toml

[unstable]

build-std-features = ["compiler-builtins-mem"]

build-std = ["core", "compiler_builtins"]

(Support for the compiler-builtins-mem feature was only added very recently, so you need at least Rust nightly 2020-09-30 for it.)

Behind the scenes, this flag enables the mem feature of the compiler_builtins crate. The effect of this is that the #[no_mangle] attribute is applied to the memcpy etc. implementations of the crate, which makes them available to the linker.

With this change, our kernel has valid implementations for all compiler-required functions, so it will continue to compile even if our code gets more complex.

Set a Default Target

To avoid passing the --target parameter on every invocation of cargo build, we can override the default target. To do this, we add the following to our cargo configuration file at .cargo/config.toml:

# in .cargo/config.toml

[build]

target = "x86_64-blog_os.json"

This tells cargo to use our x86_64-blog_os.json target when no explicit --target argument is passed. This means that we can now build our kernel with a simple cargo build. For more information on cargo configuration options, check out the official documentation.

We are now able to build our kernel for a bare metal target with a simple cargo build. However, our _start entry point, which will be called by the boot loader, is still empty. It's time that we output something to screen from it.

Printing to Screen

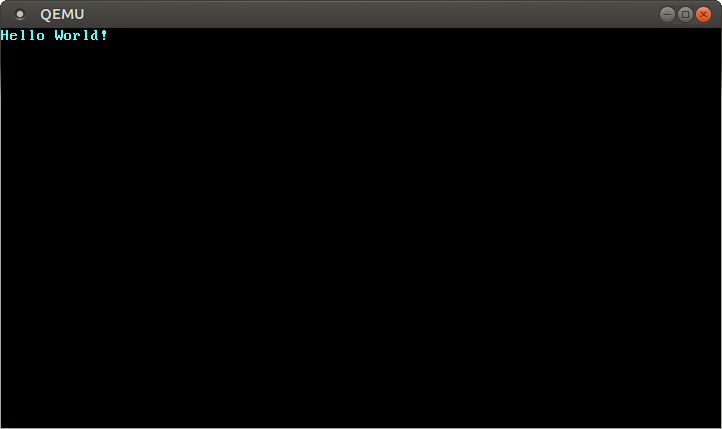

The easiest way to print text to the screen at this stage is the VGA text buffer. It is a special memory area mapped to the VGA hardware that contains the contents displayed on screen. It normally consists of 25 lines that each contain 80 character cells. Each character cell displays an ASCII character with some foreground and background colors. The screen output looks like this:

We will discuss the exact layout of the VGA buffer in the next post, where we write a first small driver for it. For printing “Hello World!”, we just need to know that the buffer is located at address 0xb8000 and that each character cell consists of an ASCII byte and a color byte.

The implementation looks like this:

static HELLO: &[u8] = b"Hello World!";

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn _start() -> ! {

let vga_buffer = 0xb8000 as *mut u8;

for (i, &byte) in HELLO.iter().enumerate() {

unsafe {

*vga_buffer.offset(i as isize * 2) = byte;

*vga_buffer.offset(i as isize * 2 + 1) = 0xb;

}

}

loop {}

}

First, we cast the integer 0xb8000 into a raw pointer. Then we iterate over the bytes of the static HELLO byte string. We use the enumerate method to additionally get a running variable i. In the body of the for loop, we use the offset method to write the string byte and the corresponding color byte (0xb is a light cyan).

Note that there's an unsafe block around all memory writes. The reason is that the Rust compiler can't prove that the raw pointers we create are valid. They could point anywhere and lead to data corruption. By putting them into an unsafe block, we're basically telling the compiler that we are absolutely sure that the operations are valid. Note that an unsafe block does not turn off Rust's safety checks. It only allows you to do five additional things.

I want to emphasize that this is not the way we want to do things in Rust! It's very easy to mess up when working with raw pointers inside unsafe blocks. For example, we could easily write beyond the buffer's end if we're not careful.

So we want to minimize the use of unsafe as much as possible. Rust gives us the ability to do this by creating safe abstractions. For example, we could create a VGA buffer type that encapsulates all unsafety and ensures that it is impossible to do anything wrong from the outside. This way, we would only need minimal amounts of unsafe code and can be sure that we don't violate memory safety. We will create such a safe VGA buffer abstraction in the next post.

Exécuter notre noyau

Maintenant que nous avons un exécutable qui fait quelque chose de perceptible, il est temps de l'exécuter. D'abord, nous devons transformer notre noyau compilé en une image de disque amorçable en le liant à un bootloader. Ensuite, nous pourrons exécuter l'image de disque dans une machine virtuelle QEMU ou l'amorcer sur du véritable matériel en utilisant une clé USB.

Créer une image d'amorçage

Pour transformer notre noyau compilé en image de disque amorçable, nous devons le lier avec un bootloader. Comme nous l'avons appris dans la [section about booting][section à propos du lancement], le bootloader est responsable de lancer le CPU et de charger notre noyau.

Plutôt que d'écrire notre propre bootloader, ce qui est un projet en soi, nous utilisons la caisse bootloader. Cette caisse propose un bootloader BIOS de base sans dépendance C, seulement du code Rust et de l'assembleur intégré. Pour l'utiliser pour lancer notre noyau, nous devons ajouter une dépendance pour cette caisse:

# dans Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

bootloader = "0.9.8"

Ajouter le bootloader comme dépendance n'est pas suffisant pour réellement créer une image de disque amorçable. Le problème est que nous devons lier notre noyau avec le bootloader après la compilation, mais cargo ne supporte pas les [post-build scripts][scripts post-build].

Pour résoudre ce problème, nous avons créé un outil nommé bootimage qui compile d'abord le noyau et le bootloader, et les lie ensuite ensemble pour créer une image de disque amorçable. Pour installer cet outil, exécutez la commande suivante dans votre terminal:

cargo install bootimage

Pour exécuter bootimage et construire le bootloader, vous devez avoir la composante rustup llvm-tools-preview installée. Vous pouvez l'installer en exécutant rustup component add llvm-tools-preview.

Après avoir installé bootimage and ajouté la composante llvm-tools-preview, nous pouvons créer une image de disque amorçable en exécutant:

> cargo bootimage

Nous voyons que l'outil recompile notre noyau en utilisant cargo build, alors il utilisera automatiquement tout changement que vous faites. Ensuite, il compile le bootloader, ce qui peut prendre un certain temps. Comme toutes les dépendances de caisses, il est seulement construit une fois puis il est mis en cache, donc les builds subséquentes seront beaucoup plus rapides. Enfin, bootimage combine le bootloader et le noyau en une image de disque amorçable.

Après avoir exécuté la commande, vous devriez voir une image de disque amorçable nommée bootimage-blog_os.bin dans votre dossier target/x86_64-blog_os/debug. Vous pouvez la lancer dans une machine virtuelle ou la copier sur une clé USB pour la lancer sur du véritable matériel. (Notez que ceci n'est pas une image CD, qui est un format différent, donc la graver sur un CD ne fonctionne pas).

Comment cela fonctionne-t-il?

L'outil bootimage effectue les étapes suivantes en arrière-plan:

- Il compile notre noyau en un fichier ELF.

- Il compile notre dépendance bootloader en exécutable autonome.

- Il lie les octets du fichier ELF noyau au bootloader.

Lorsque lancé, le bootloader lit et analyse le fichier ELF ajouté. Il associe ensuite les segments du programme aux adresses virtuelles dans les tables de pages, réinitialise la section .bss, puis met en place une pile. Finalement, il lit le point d'entrée (notre fonction _start) et s'y rend.

Amorçage dans QEMU

Nous pouvons maintenant lancer l'image disque dans une machine virtuelle. Pour la démarrer dans QEMU, exécutez la commande suivante :

> qemu-system-x86_64 -drive format=raw,file=target/x86_64-blog_os/debug/bootimage-blog_os.bin

warning: TCG doesn't support requested feature: CPUID.01H:ECX.vmx [bit 5]

Ceci ouvre une fenêtre séparée qui devrait ressembler à cela:

Nous voyoons que notre "Hello World!" est visible à l'écran.

Véritable ordinateur

Il est aussi possible d'écrire l'image disque sur une clé USB et de le lancer sur un véritable ordinateur, mais soyez prudent et choisissez le bon nom de périphérique, parce que tout sur ce périphérique sera écrasé:

> dd if=target/x86_64-blog_os/debug/bootimage-blog_os.bin of=/dev/sdX && sync

Où sdX est le nom du périphérique de votre clé USB.

Après l'écriture de l'image sur votre clé USB, vous pouvez l'exécuter sur du véritable matériel en l'amorçant à partir de la clé USB. Vous devrez probablement utiliser un menu d'amorçage spécial ou changer l'ordre d'amorçage dans votre configuration BIOS pour amorcer à partir de la clé USB. Notez que cela ne fonctionne actuellement pas avec des ordinateurs UEFI, puisque la caisse bootloader ne supporte pas encore UEFI.

Utilisation de cargo run

Pour faciliter l'exécution de notre noyau dans QEMU, nous pouvons définir la clé de configuration runner pour cargo:

# dans .cargo/config.toml

[target.'cfg(target_os = "none")']

runner = "bootimage runner"

La table target.'cfg(target_os = "none")' s'applique à toutes les cibles dont le champ "os" dans le fichier de configuration est défini à "none". Ceci inclut notre cible x86_64-blog_os.json. La clé runner key spécifie la commande qui doit être invoquée pour cargo run. La commande est exécutée après une build réussie avec le chemin de l'exécutable comme premier argument. Voir la configuration cargo pour plus de détails.

La commande bootimage runner est spécifiquement conçue pour être utilisable comme un exécutable runner. Elle lie l'exécutable fourni avec le bootloader duquel le projet dépend et lance ensuite QEMU. Voir le [Readme of bootimage][README de bootimage] pour plus de détails et les options de configuration possibles.

Nous pouvons maintenant utiliser cargo run pour compiler notre noyau et le lancer dans QEMU.

Et ensuite?

Dans le prochain article, nous explorerons le tampon texte VGA plus en détails et nous écrirons une interface sécuritaire pour l'utiliser. Nous allons aussi mettre en place la macro println.