81 KiB

+++ title = "Heap Allocation" weight = 10 path = "heap-allocation" date = 0000-01-01 +++

TODO

This blog is openly developed on GitHub. If you have any problems or questions, please open an issue there. You can also leave comments at the bottom. The complete source code for this post can be found in the post-10 branch.

Local and Static Variables

We currently use two types of variables in our kernel: local variables and static variables. Local variables are stored on the call stack and are only valid until the surrounding function returns. Static variables are stored at a fixed memory location and always live for the complete lifetime of the program.

Local Variables

Local variables are stored on the call stack, which is a stack data structure that supports push and pop operations. On each function entry, the parameters, the return address, and the local variables of the called function are pushed by the compiler:

The above example shows the call stack after an outer function called an inner function. We see that the call stack contains the local variables of outer first. On the inner call, the parameter 1 and the return address for the function were pushed. Then control was transferred to inner, which pushed its local variables.

After the inner function returns, its part of the call stack is popped again and only the local variables of outer remain:

We see that the local variables of inner only live until the function returns. The Rust compiler enforces these lifetimes and throws an error when we for example try to return a reference to a local variable:

fn inner(i: usize) -> &'static u32 {

let z = [1, 2, 3];

&z[i]

}

(run the example on the playground)

While returning a reference makes no sense in this example, there are cases where we want a variable to live longer than the function. We already saw such a case in our kernel when we tried to load an interrupt descriptor table and had to use a static variable to extend the lifetime.

Static Variables

Static variables are stored at a fixed memory location separate from the stack. This memory location is assigned at compile time by the linker and encoded in the executable. Statics live for the complete runtime of the program, so they have the 'static lifetime and can always be referenced from local variables:

When the inner function returns in the above example, it's part of the call stack is destroyed. The static variables live in a separate memory range that is never destroyed, so the &Z[1] reference is still valid after the return.

Apart from the 'static lifetime, static variables also have the useful property that their location is known at compile time, so that no reference is needed for accessing it. We utilized that property for our println macro: By using a static Writer internally there is no &mut Writer reference needed to invoke the macro, which is very useful in exception handlers where we don't have access to any non-local references.

However, this property of static variables brings a crucial drawback: They are read-only by default. Rust enforces this because a data race would occur if e.g. two threads modify a static variable at the same time. The only way to modify a static variable is to encapsulate it in a Mutex type, which ensures that only a single &mut reference exists at any point in time. We used a Mutex for our static VGA buffer Writer.

Dynamic Memory

Local and static variables are already very powerful together and enable most use cases. However, we saw that they both have their limitations:

- Local variables only live until the end of the surrounding function or block (or shorter with non lexical lifetimes). This is because they live on the call stack and are destroyed after the surrounding function returns.

- Static variables always live for the complete runtime of the program, so there is no way to reclaim and reuse their memory when they're no longer needed. Also, they have unclear ownership semantics and are accessible from all functions, so they need to be protected by a

Mutexwhen we want to modify them.

Another limitation of local and static variables is that they have a fixed size. So they can't store a collection that dynamically grows when more elements are added. (There are proposals for unsized rvalues in Rust that would allow dynamically sized local variables, but they only work in some specific cases.)

To circumvent these drawbacks, programming languages often support a third memory region for storing variables called the heap. The heap supports dynamic memory allocation at runtime through two functions called allocate and deallocate. It works in the following way: The allocate function returns a free chunk of memory of the specified size that can be used to store a variable. This variable then lives until it is freed by calling the deallocate function with a reference to the variable.

Let's go through an example:

Here the inner function uses heap memory instead of static variables for storing z. It first allocates a memory block of the required size, which returns a *mut u8 raw pointer. It then uses the ptr::write method to write the array [1,2,3] to it. In the last step, it uses the offset function to calculate a pointer to the ith element and returns it. (Note that we omitted some required casts and unsafe blocks in this example function for brevity.)

The allocated memory lives until it is explicitly freed through a call to deallocate. Thus, the returned pointer is still valid even after inner returned and its part of the call stack was destroyed. The advantage of using heap memory compared to static memory is that the memory can be reused after it is freed, which we do through the deallocate call in outer. After that call, the situation looks like this:

We see that the z[1] slot is free again and can be reused for the next allocate call. However, we also see that z[0] and z[2] are never freed because we never deallocate them. Such a bug is called a memory leak and often the cause of excessive memory consumption of programs (just imagine what happens when we call inner repeatedly in a loop). This might seem bad, but there much more dangerous types of bugs that can happen with dynamic allocation.

Common Errors

Apart from memory leaks, which are unfortunate but don't make the program vulnerable to attackers, there are two common types of bugs with more severe consequences:

- When we accidentally continue to use a variable after calling

deallocateon it, we have a so-called use-after-free vulnerability. Such a bug can often exploited by attackers to execute arbitrary code. - When we accidentally free a variable twice, we have a double-free vulnerability. This is problematic because it might free a different a different allocation that was allocated in the same spot after the first

deallocatecall. Thus, it can lead to an use-after-free vulnerability again.

These types of vulnerabilities are commonly known, so one might expect that people learned how to avoid them by now. But no, there are still new such vulnerabilities found today, for example this recent use-after-free vulnerability in Linux that allowed arbitrary code execution. This shows that even the best programmers are not always able to correctly handle dynamic memory in complex projects.

To avoid these issues, many languages such as Java or Python manage dynamic memory automatically using a technique called garbage collection. The idea is that the programmer never invokes deallocate manually. Instead, the programm is regularly paused and scanned for unused heap variables, which are then automatically deallocated. Thus, the above vulnerabilities can never occur. The drawbacks are the performance overhead of the regular scan and the probaby long pause times.

Rust takes a different approach to the problem: It uses a concept called ownership that is able to check the correctness of dynamic memory operations at compile time. Thus no garbage collection is needed and the programmer has fine-grained control over the use of dynamic memory just like in C or C++, but the compiler guarantees that none of the mentioned vulnerabilities can occur.

Allocations in Rust

First, instead of letting the programmer manually call allocate and deallocate, the Rust standard library provides abstraction types that call these functions implicitly. The most important type is Box, which is an abstraction for a heap-allocated value. It provides a Box::new constructor function that takes a value, calls allocate with the size of the value, and then moves the value to the newly allocated slot on the heap. To free the heap memory again, the Box type implements the Drop trait to call deallocate when it goes out of scope:

{

let z = Box::new([1,2,3]);

[…]

} // z goes out of scope and `deallocate` is called

This pattern has the strange name resource acquisition is initialization (or RAII for short). It originated in C++, where it is used to implement a similar abstraction type called std::unique_ptr.

Such a type alone does not suffice to prevent all use-after-free bugs since programmers can still hold on to references after the Box goes out of scope and the corresponding heap memory slot is deallocated:

let x = {

let z = Box::new([1,2,3]);

&z[1]

}; // z goes out of scope and `deallocate` is called

println!("{}", x);

This is where Rust's ownership comes in. It assigns an abstract lifetime to each reference, which is the scope in which the reference is valid. In the above example, the x reference is taken from the z array, so it becomes invalid after z goes out of scope. When you run the above example on the playground you see that the Rust compiler indeed throws an error:

error[E0597]: `z[_]` does not live long enough

--> src/main.rs:4:9

|

2 | let x = {

| - borrow later stored here

3 | let z = Box::new([1,2,3]);

4 | &z[1]

| ^^^^^ borrowed value does not live long enough

5 | }; // z goes out of scope and `deallocate` is called

| - `z[_]` dropped here while still borrowed

The terminology can be a bit confusing at first. Taking a reference to a value is called borrowing the value since it's similar to a borrow in real life: You have temporary access to an object but need to return it sometime and you must not destroy it. By checking that all borrows end before an object is destroyed, the Rust compiler can guarantee that no use-after-free situation can occur.

Rust's ownership system goes even further and does not only prevent use-after-free bugs, but provides complete memory safety like garbage collected languages like Java or Python do. Additionally, it guarantees thread safety and is thus even safer than those languages in multi-threaded code. And most importantly, all these checks happen at compile time, so there is no runtime overhead compared to hand written memory management in C.

Use Cases

We now know the basics of dynamic memory allocation in Rust, but when should we use it? We've come really far with our kernel without dynamic memory allocation, so why do we need it now?

First, dynamic memory allocation always comes with a bit of performance overhead, since we need to find a free slot on the heap for every allocation. For this reason local variables are generally preferable. However, there are cases where dynamic memory allocation is needed or where using it is preferable.

As a basic rule, dynamic memory is required for variables that have a dynamic lifetime or a variable size. The most important type with a dynamic lifetime is Rc, which counts the references to its wrapped value and deallocates it after all references went out of scope. Examples for types with a variable size are Vec, String, and other collection types that dynamically grow when more elements are added. These types work by allocating a larger amount of memory when they become full, copying all elements over, and then deallocating the old allocation.

For our kernel we will mostly need the collection types, for example for storing a list of active tasks when implementing multitasking in the next posts.

The Allocator Interface

The first step in implementing a heap allocator is to add a dependency on the built-in alloc crate. Like the core crate, it is a subset of the standard library that additionally contains the allocation and collection types. To add the dependency on alloc, we add the following to our lib.rs:

// in src/lib.rs

extern crate alloc;

Contrary to normal dependencies, we don't need to modify the Cargo.toml. The reason is that the alloc crate ships with the Rust compiler as part of the standard library, so we just need to enable it. This is what this extern crate statement does. (Historically, all dependencies needed an extern crate statement, which is now optional).

The reason that the alloc crate is disabled by default in #[no_std] crates is that it has additional requirements. We can see these requirements as errors when we try to compile our project now:

error: no global memory allocator found but one is required; link to std or add

#[global_allocator] to a static item that implements the GlobalAlloc trait.

error: `#[alloc_error_handler]` function required, but not found

The first error occurs because the alloc crate requires an heap allocator. A heap allocator is an object that provides the allocate and deallocate functions that we mentioned above. In Rust, the heap allocator is described by the GlobalAlloc trait, which is mentioned in the error message. To set the heap allocator for the crate, the #[global_allocator] attribute must be applied to a static variable that implements the GlobalAlloc trait.

The second error occurs because calls to allocate can fail, most commonly when there is no more memory available. Our program must be able to react to this case, which is what the #[alloc_error_handler] function is for.

We will describe these traits and attributes in detail in the following sections.

The GlobalAlloc Trait

The GlobalAlloc trait defines the functions that a heap allocator must provide. All heap allocators must implement it. The trait is special because it is almost never used directly by the programmer. Instead, the compiler will automatically insert the appropriate calls to the trait methods when using the allocation and collection types of alloc.

Since we will need to implement the trait for all our allocator types, it is worth taking a closer look at its declaration:

pub unsafe trait GlobalAlloc {

unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8;

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout);

unsafe fn alloc_zeroed(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8 { ... }

unsafe fn realloc(

&self,

ptr: *mut u8,

layout: Layout,

new_size: usize

) -> *mut u8 { ... }

}

It defines the two required methods alloc and dealloc, which correspond to the allocate and deallocate functions we used in our examples:

- The

allocmethod takes aLayoutinstance as argument, which describes the desired size and alignment that the allocated memory should have. It returns a raw pointer to the first byte of the allocated memory block. Instead of an explicit error value, theallocmethod returns a null pointer to signal an allocation error. This is a bit non-idiomatic, but it has the advantage that wrapping existing system allocators is easy, since they use the same convention. - The

deallocmethod is the counterpart and responsible for freeing a memory block again. It receives the pointer returned byallocand theLayoutthat was used for the allocation as arguments.

The trait additionally defines the two methods alloc_zeroed and realloc with default implementations:

- The

alloc_zeroedmethod is equivalent to callingallocand then setting the allocated memory block to zero, which is exactly what the provided default implementation does. An allocator implementations can override the default implementations with a more efficient custom implementation if possible. - The

reallocmethod allows to grow or shrink an allocation. The default implementation allocates a new memory block with the desired size and copies over all the content from the previous allocation. Again, an allocator implementation can probably provide a more efficient implementation of this method, for example by growing/shrinking the allocation in-place if possible.

Unsafety

One thing to notice is that both the trait itself and all trait methods are declared as unsafe:

- The reason for declaring the trait as

unsafeis that the programmer must guarantee that the trait implementation for an allocator type is correct. For example, theallocmethod must never return a memory block that is already used somewhere else because this would cause undefined behavior. - Similarly, the reason that the methods are

unsafeis that the caller must ensure various invariants when calling the methods, for example that theLayoutpassed toallocspecifies a non-zero size. This is not really relevant in practice since the methods are normally called directly by the compiler, which ensures that the requirements are met.

A DummyAllocator

Now that we know what an allocator type should provide, we can create a simple dummy allocator. For that we create a new allocator module:

// in src/lib.rs

pub mod allocator;

Our dummy allocator will do the absolute minimum to implement the trait and always return an error when alloc is called. It looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

use alloc::alloc::{GlobalAlloc, Layout};

use core::ptr::null_mut;

pub struct Dummy;

unsafe impl GlobalAlloc for Dummy {

unsafe fn alloc(&self, _layout: Layout) -> *mut u8 {

null_mut()

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, _ptr: *mut u8, _layout: Layout) {

panic!("dealloc should be never called")

}

}

The struct does not need any fields, so we create it as a zero sized type. As mentioned above, we always return the null pointer from alloc, which corresponds to an allocation error. Since the allocator never returns any memory, a call to dealloc should never occur. For this reason we simply panic in the dealloc method. The alloc_zeroed and realloc methods have default implementations, so we don't need to provide implementations for them.

We now have a simple allocator, but we still have to tell the Rust compiler that it should use this allocator. This is where the #[global_allocator] attribute comes in.

The #[global_allocator] Attribute

The #[global_allocator] attribute tells the Rust compiler which allocator instance it should use as the global heap allocator. The attribute is only applicable to a static that implements the GlobalAlloc trait. Let's register an instance of our Dummy allocator as the global allocator:

// in src/lib.rs

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOCATOR: allocator::Dummy = allocator::Dummy;

Since the Dummy allocator is a zero sized type, we don't need to specify any fields in the initialization expression. Note that the #[global_allocator] module cannot be used in submodules, so we need to put it into the lib.rs.

When we now try to compile it, the first error should be gone. Let's fix the remaining second error:

error: `#[alloc_error_handler]` function required, but not found

The #[alloc_error_handler] Attribute

As we learned when discussing the GlobalAlloc trait, the alloc function can signal an allocation error by returning a null pointer. The question is: how should the Rust runtime react to such an allocation failure. This is where the #[alloc_error_handler] attribute comes in. It specifies a function that is called when an allocation error occurs, similar to how our panic handler is called when a panic occurs.

Let's add such a function to fix the compilation error:

// in src/lib.rs

#![feature(alloc_error_handler)] // at the top of the file

#[alloc_error_handler]

fn alloc_error_handler(layout: alloc::alloc::Layout) -> ! {

panic!("allocation error: {:?}", layout)

}

The alloc_error_handler function is still unsafe, so we need a feature gate to enable it. The function receives a single argument: the Layout instance that was passed to alloc when the allocation failure occurred. There's nothing we can do to resolve that failure, so we just panic with a message that contains the Layout instance.

With this function, compilation errors should be fixed. Now we can use the allocation and collection types of alloc, for example we can use a Box to allocate a value on the heap:

// in src/main.rs

extern crate alloc;

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// […] print "Hello World!", call `init`, create `mapper` and `frame_allocator`

let x = Box::new(41);

// […] call `test_main` in test mode

println!("It did not crash!");

blog_os::hlt_loop();

}

Note that we need to specify the extern crate alloc statement in our main.rs too. This is required because the lib.rs and main.rs part are treated as separate crates. However, we don't need to create another #[global_allocator] static because the global allocator applies to all crates in the project. In fact, specifying an additional allocator in another crate would be an error.

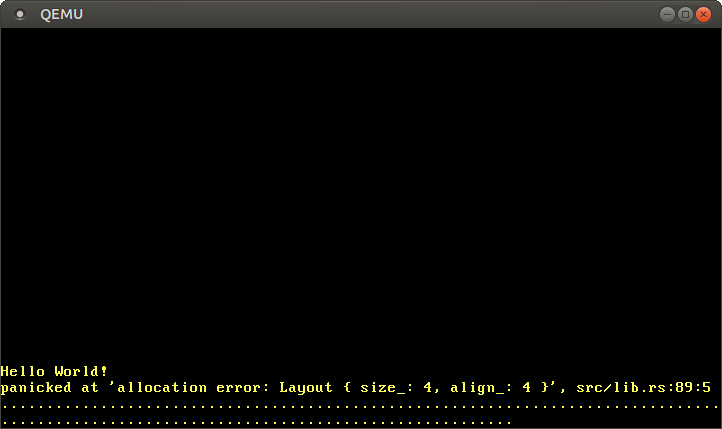

When we run the above code, we see that our alloc_error_handler function is called:

The error handler is called because the Box::new function implicitly calls the alloc function of the global allocator. Our dummy allocator always returns a null pointer, so every allocation fails. To fix this we need to create an allocator that actually returns usable memory.

Heap Memory

Before we can create a proper allocator, we first need to create a heap memory region from which the allocator can allocate memory. To do this, we need to define a virtual memory range for the heap region and then map this region to physical frames. See the "Introduction To Paging" post for an overview of virtual memory and page tables.

The first step is to define a virtual memory region for the heap. We can choose any virtual address range that we like, as long as it is not already used for a different memory region. Let's define it as the memory starting at address 0x_4444_4444_0000 so that we can easily recognize a heap pointer later:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub const HEAP_START: usize = 0x_4444_4444_0000;

pub const HEAP_SIZE: usize = 100 * 1024; // 100 KiB

We set the heap size to 1 KiB for now. If we need more space in the future, we can simply increase it.

If we tried to use this heap region now, a page fault would occur since the virtual memory region is not mapped to physical memory yet. To resolve this, we create an init_heap function that maps the heap pages using the Mapper API that we introduced in the "Paging Implementation" post:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub fn init_heap(

mapper: &mut impl Mapper<Size4KiB>,

frame_allocator: &mut impl FrameAllocator<Size4KiB>,

) -> Result<(), MapToError> {

let page_range = {

let heap_start = VirtAddr::new(HEAP_START as u64);

let heap_end = heap_start + HEAP_SIZE - 1u64;

let heap_start_page = Page::containing_address(heap_start);

let heap_end_page = Page::containing_address(heap_end);

Page::range_inclusive(heap_start_page, heap_end_page)

};

for page in page_range {

let frame = frame_allocator

.allocate_frame()

.ok_or(MapToError::FrameAllocationFailed)?;

let flags = PageTableFlags::PRESENT | PageTableFlags::WRITABLE;

unsafe { mapper.map_to(page, frame, flags, frame_allocator)?.flush() };

}

Ok(())

}

The function takes mutable references to a Mapper and a FrameAllocator instance, both limited to 4KiB pages by using Size4KiB as generic parameter. The return value of the function is a Result with the unit type () as success variant and a MapToError as error variant, which is the error type returned by the Mapper::map_to method. Reusing the error type makes sense here because the map_to method is the main source of errors in this function.

The implementation can be broken down into two parts:

-

Creating the page range:: To create a range of the pages that we want to map, we convert the

HEAP_STARTpointer to aVirtAddrtype. Then we calculate the heap end address from it by adding theHEAP_SIZE. We want an inclusive bound (the address of the last byte of the heap), so we subtract 1. Next, we convert the addresses intoPagetypes using thecontaining_addressfunction. Finally, we create a page range from the start and end pages using thePage::range_inclusivefunction. -

Mapping the pages: The second step is to map all pages of the page range we just created. For that we iterate over the pages in that range using a

forloop. For each page, we do the following:-

We allocate a physical frame that the page should be mapped to using the

FrameAllocator::allocate_framemethod. This method returnsNonewhen there are no more frames left. We deal with that case by mapping it to aMapToError::FrameAllocationFailederror through theOption::ok_ormethod and then apply the question mark operator to return early in the case of an error. -

We set the required

PRESENTflag and theWRITABLEflag for the page. With these flags both read and write accesses are allowed, which makes sense for heap memory. -

We use the unsafe

Mapper::map_tomethod for creating the mapping in the active page table. The method can fail, therefore we use the question mark operator again to forward the error to the caller. On success, the method returns aMapperFlushinstance that we can use to update the translation lookaside buffer using theflushmethod.

-

The final step is to call this function from our kernel_main:

// in src/main.rs

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

use blog_os::allocator; // new import

use blog_os::memory::{self, BootInfoFrameAllocator};

println!("Hello World{}", "!");

blog_os::init();

let mut mapper = unsafe { memory::init(boot_info.physical_memory_offset) };

let mut frame_allocator = unsafe {

BootInfoFrameAllocator::init(&boot_info.memory_map)

};

// new

allocator::init_heap(&mut mapper, &mut frame_allocator)

.expect("heap initialization failed");

let x = Box::new(41);

// […] call `test_main` in test mode

println!("It did not crash!");

blog_os::hlt_loop();

}

We show the full function for context here. The only new lines are the blog_os::allocator import and the call to allocator::init_heap function. In case the init_heap function returns an error, we panic using the Result::expect method since there is currently no sensible way for us to handle this error.

We now have a mapped heap memory region that is ready to be used. The Box::new call still uses our old Dummy allocator, so you will still see the "out of memory" error when you run it. Let's fix this by creating some proper allocators.

Allocator Designs

The responsibility of an allocator is to manage the available heap memory. It needs to return unused memory on alloc calls and keep track of memory freed by dealloc so that it can be reused again. Most importantly, it must never hand out memory that is already in use somewhere else because this would cause undefined behavior.

There are many different ways to design an allocator. While some approaches are obviously useless like our Dummy allocator, there are many different allocator designs with valid use cases. For this reason we present multiple possible designs and explain where they could be useful.

TODO userspace vs kernel allocators

Bump Allocator

The most simple allocator design is a bump allocator. It allocates memory linearly and only keeps track of the number of allocated bytes and the number of allocations. It is only useful in very specific use cases because it has a severe limitation: it can only free all memory at once.

The base type looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub struct BumpAllocator {

heap_start: usize,

heap_end: usize,

next: usize,

allocations: usize,

}

impl BumpAllocator {

/// Creates a new bump allocator with the given heap bounds.

///

/// This method is unsafe because the caller must ensure that the given

/// memory range is unused.

pub const unsafe fn new(heap_start: usize, heap_size: usize) -> Self {

BumpAllocator {

heap_start,

heap_end: heap_start + heap_size,

next: heap_start,

allocations: 0,

}

}

}

Instead of using the HEAP_START and HEAP_SIZE constants directly, we use separate heap_start and heap_end fields. This makes the type more flexible, for example it also works when we only want to assign a part of the heap region. The purpose of the next field is to always point to the first unused byte of the heap, i.e. the start address of the next allocation. The allocations field is a simple counter for the active allocations with the goal of resetting the allocator after the last allocation was freed.

We provide a simple constructor function that creates a new BumpAllocator. It initializes the heap_start and heap_end fields with the given values and the allocations counter with 0. The next field is set to heap_start since the whole heap should be unused at this point. Since this is something that the caller must guarantee, the function needs to be unsafe. Given an invalid memory range, the planned implementation of the GlobalAlloc trait would cause undefined behavior when it is used as global allocator.

A Locked Wrapper

Implementing the GlobalAlloc trait directly for the BumpAllocator struct is not possible. The problem is that the alloc and dealloc methods of the trait only take an immutable &self reference, but we need to update the next and allocations fields for every allocation. The reason that the GlobalAlloc trait is specified this way is that the global allocator needs to be stored in an immutable static that only allows &self references.

To be able to implement the trait for our BumpAllocator struct, we need to add synchronized interior mutability to get mutable field access through the &self reference. A type that adds the required synchronization and allows interior mutabilty is the spin::Mutex spinlock that we already used multiple times for our kernel, for example for our VGA buffer writer. To use it, we create a Locked wrapper type:

// in src/allocator.rs

pub struct Locked<A> {

inner: spin::Mutex<A>,

}

impl<A> Locked<A> {

pub const fn new(inner: A) -> Self {

Locked {

inner: spin::Mutex::new(inner),

}

}

}

The type is a generic wrapper around a spin::Mutex<A>. It imposes no restrictions on the wrapped type A, so it can be used to wrap all kinds of types, not just allocators. It provides a simple new constructor function that wraps a given value.

Implementing GlobalAlloc

With the help of the Locked wrapper type we now can implement the GlobalAlloc trait for our bump allocator. The trick is to implement the trait not for the BumpAllocator directly, but for the wrapped Locked<BumpAllocator> type. The implementation looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

unsafe impl GlobalAlloc for Locked<BumpAllocator> {

unsafe fn alloc(&self, layout: Layout) -> *mut u8 {

let mut bump = self.inner.lock();

let alloc_start = align_up(bump.next, layout.align());

let alloc_end = alloc_start + layout.size();

if alloc_end > bump.heap_end {

null_mut() // out of memory

} else {

bump.next = alloc_end;

bump.allocations += 1;

alloc_start as *mut u8

}

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&self, _ptr: *mut u8, _layout: Layout) {

let mut bump = self.inner.lock();

bump.allocations -= 1;

if bump.allocations == 0 {

bump.next = bump.heap_start;

}

}

}

The first step for both alloc and dealloc is to call the Mutex::lock method to get a mutable reference to the wrapped allocator type. The instance remains locked until the end of the method, so that no data race can occur in multithreaded contexts (we will add threading support soon).

The alloc implementation first performs the required alignment on the next address, specified through the given Layout. The code for the align_up function is shown below. This yields the start address of the allocation. Next, we add the requested allocation size to alloc_start to get the end address of the allocation. If it is larger than the end address of the heap, we return a null pointer since there is not enough memory available. Otherwise, we update the next address (the next allocation should start after the current allocation), increase the allocations counter by 1, and return the alloc_start address converted to a *mut u8 pointer.

The dealloc function ignores the given pointer and Layout arguments. Instead, it just decreases the allocations counter. If the counter reaches 0 again, it means that all allocations were freed again. In this case, it resets the next address to the heap_start address to make the complete heap memory available again.

The last remaining part of the implementation is the align_up function, which looks like this:

// in src/allocator.rs

fn align_up(addr: usize, align: usize) -> usize {

let remainder = addr % align;

if remainder == 0 {

addr // addr already aligned

} else {

addr - remainder + align

}

}

The function first computes the remainder of the division of addr by align. If the remainder is 0, the address is already aligned with the given alignment. Otherwise, we align the address by subtracting the remainder (so that the new remainder is 0) and then adding the alignment (so that the address does not become smaller than the original address).

Using It

To use the bump allocator instead of the dummy allocator, we need to update the ALLOCATOR static in lib.rs:

// in src/lib.rs

use allocator::{Locked, BumpAllocator, HEAP_START, HEAP_SIZE};

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOCATOR: Locked<BumpAllocator> =

Locked::new(BumpAllocator::new(HEAP_START, HEAP_SIZE));

Here it becomes important that we declared both the Locked::new and the BumpAllocator::new as const functions. If they were normal functions, a compilation error would occur because the initialization expression of a static must evaluatable at compile time.

Now we can perform heap allocation without runtime errors:

// in src/main.rs

use alloc::{boxed::Box, vec::Vec, collections::BTreeMap};

fn kernel_main(boot_info: &'static BootInfo) -> ! {

// […] initialize interrupts, mapper, frame_allocator, heap

// allocate a number on the heap

let heap_value = Box::new(41);

println!("heap_value at {:p}", heap_value);

// create a dynamically sized vector

let mut vec = Vec::new();

for i in 0..500 {

vec.push(i);

}

println!("vec at {:p}", vec.as_slice());

// try to create one billion boxes

for _ in 0..1_000_000_000 {

let _ = Box::new(1);

}

// […] call `test_main` in test context

println!("It did not crash!");

blog_os::hlt_loop();

}

This code example showcases a few collection types of the alloc crate. Of course, there are many more allocation and collection types in that crate that we can now all use in our kernel, including:

- the reference counted pointers

RcandArc - the owned string type

Stringand theformat!macro LinkedList- the growable ring buffer

VecDeque BinaryHeapBTreeMapandBTreeSet

When we run our project now, we see the following:

As expected, we see that the Box and Vec values live on the heap, as indicated by the pointer starting with 0x_4444_4444. The reason that the vector starts at offset 0x800 is not that the boxed value is 0x800 bytes large, but the reallocations that occur when the vector needs to increase its capacity. For example, when the vectors capacity is 32 and we try to add the next element, the vector allocates a new backing array with capacity 64 behind the scenes and copies all elements over. Then it frees the old allocation, which in our case is equivalent to leaking it since our bump allocator doesn't reuse freed memory.

While the basic Box and Vec examples work as expected, our loop that tries to create one billion boxes causes a panic. The reason is that the bump allocator never reuses freed memory, so that for each created Box a few bytes are leaked. This makes the bump allocator unsuitable for many applications in practice, apart from some very specific use cases.

When to use a Bump Allocator

The big advantage of bump allocation is that it's very fast. Compared to other allocator designs (see below) that need to actively look for a fitting memory block and perform various bookkeeping tasks on alloc and dealloc, a bump allocator can be optimized to just a few assembly instructions. This makes bump allocators useful for optimizing the allocation performance, for example when creating a virtual DOM library.

While a bump allocator is seldom used as the global allocator, the principle of bump allocation is often applied in form of arena allocation, which in principle batches individual allocations together to improve performance. An example for an arena allocator for Rust is the toolshed crate.

TODO explanation

TODO &self problem

In this form the allocator is not useful since the deallocated memory is never freed. This isn't something that we can add easily, because memory regions might be deallocated in a different order than they were allocated. So a single pointer does not suffice to hold this information.

However, there is one possible way to free memory with a bump allocator: We can reset the whole heap after the last memory region is deallocated. To implement this, we add an additional counter field:

TODO

Bitmap Allocator

LinkedList Allocator

Bucket Allocator

Summary

What's next?

old

A good allocator is fast and reliable. It also effectively utilizes the available memory and keeps fragmentation low. Furthermore, it works well for concurrent applications and scales to any number of processors. It even optimizes the memory layout with respect to the CPU caches to improve cache locality and avoid false sharing.

These requirements make good allocators pretty complex. For example, [jemalloc] has over 30.000 lines of code. This complexity is out of scope for our kernel, so we will create a much simpler allocator. Nevertheless, it should suffice for the foreseeable future, since we'll allocate only when it's absolutely necessary.

The Allocator Interface

The allocator interface in Rust is defined through the Alloc trait, which looks like this:

pub unsafe trait Alloc {

unsafe fn alloc(&mut self, layout: Layout) -> Result<*mut u8, AllocErr>;

unsafe fn dealloc(&mut self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout);

[…] // about 13 methods with default implementations

}

The alloc method should allocate a memory block with the size and alignment given through Layout parameter. The deallocate method should free such memory blocks again. Both methods are unsafe, as is the trait itself. This has different reasons:

- Implementing the

Alloctrait is unsafe, because the implementation must satisfy a set of contracts. Among other things, pointers returned byallocmust point to valid memory and adhere to theLayoutrequirements. - Calling

allocis unsafe because the caller must ensure that the passed layout does not have size zero. I think this is because of compatibility reasons with existing C-allocators, where zero-sized allocations are undefined behavior. - Calling

deallocis unsafe because the caller must guarantee that the passed parameters adhere to the contract. For example,ptrmust denote a valid memory block allocated via this allocator.

To set the system allocator, the global_allocator attribute can be added to a static that implements Alloc for a shared reference of itself. For example:

#[global_allocator]

static MY_ALLOCATOR: MyAllocator = MyAllocator {...};

impl<'a> Alloc for &'a MyAllocator {

unsafe fn alloc(&mut self, layout: Layout) -> Result<*mut u8, AllocErr> {...}

unsafe fn dealloc(&mut self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout) {...}

}

Note that Alloc needs to be implemented for &MyAllocator, not for MyAllocator. The reason is that the alloc and dealloc methods require mutable self references, but there's no way to get such a reference safely from a static. By requiring implementations for &MyAllocator, the global allocator interface avoids this problem and pushes the burden of synchronization onto the user.

Including the alloc crate

The Alloc trait is part of the alloc crate, which like core is a subset of Rust's standard library. Apart from the trait, the crate also contains the standard types that require allocations such as Box, Vec and Arc. We can include it through a simple extern crate:

// in src/lib.rs

#![feature(alloc)] // the alloc crate is still unstable

[...]

#[macro_use]

extern crate alloc;

We don't need to add anything to our Cargo.toml, since the alloc crate is part of the standard library and shipped with the Rust compiler. The alloc crate provides the format! and vec! macros, so we use #[macro_use] to import them.

When we try to compile our crate now, the following error occurs:

error[E0463]: can't find crate for `alloc`

--> src/lib.rs:10:1

|

16 | extern crate alloc;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ can't find crate

The problem is that xargo only cross compiles libcore by default. To also cross compile the alloc crate, we need to create a file named Xargo.toml in our project root (right next to the Cargo.toml) with the following content:

[target.x86_64-blog_os.dependencies]

alloc = {}

This instructs xargo that we also need alloc. It still doesn't compile, since we need to define a global allocator in order to use the alloc crate:

error: no #[default_lib_allocator] found but one is required; is libstd not linked?

A Bump Allocator

For our first allocator, we start simple. We create a memory::heap_allocator module containing a so-called bump allocator:

// in src/memory/mod.rs

mod heap_allocator;

// in src/memory/heap_allocator.rs

use alloc::heap::{Alloc, AllocErr, Layout};

/// A simple allocator that allocates memory linearly and ignores freed memory.

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct BumpAllocator {

heap_start: usize,

heap_end: usize,

next: usize,

}

impl BumpAllocator {

pub const fn new(heap_start: usize, heap_end: usize) -> Self {

Self { heap_start, heap_end, next: heap_start }

}

}

unsafe impl Alloc for BumpAllocator {

unsafe fn alloc(&mut self, layout: Layout) -> Result<*mut u8, AllocErr> {

let alloc_start = align_up(self.next, layout.align());

let alloc_end = alloc_start.saturating_add(layout.size());

if alloc_end <= self.heap_end {

self.next = alloc_end;

Ok(alloc_start as *mut u8)

} else {

Err(AllocErr::Exhausted{ request: layout })

}

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&mut self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout) {

// do nothing, leak memory

}

}

We also need to add #![feature(allocator_api)] to our lib.rs, since the allocator API is still unstable.

The heap_start and heap_end fields contain the start and end address of our kernel heap. The next field contains the next free address and is increased after every allocation. To allocate a memory block we align the next address using the align_up function (described below). Then we add up the desired size and make sure that we don't exceed the end of the heap. We use a saturating add so that the alloc_end cannot overflow, which could lead to an invalid allocation. If everything goes well, we update the next address and return a pointer to the start address of the allocation. Else, we return None.

Alignment

In order to simplify alignment, we add align_down and align_up functions:

/// Align downwards. Returns the greatest x with alignment `align`

/// so that x <= addr. The alignment must be a power of 2.

pub fn align_down(addr: usize, align: usize) -> usize {

if align.is_power_of_two() {

addr & !(align - 1)

} else if align == 0 {

addr

} else {

panic!("`align` must be a power of 2");

}

}

/// Align upwards. Returns the smallest x with alignment `align`

/// so that x >= addr. The alignment must be a power of 2.

pub fn align_up(addr: usize, align: usize) -> usize {

align_down(addr + align - 1, align)

}

Let's start with align_down: If the alignment is a valid power of two (i.e. in {1,2,4,8,…}), we use some bitwise operations to return the aligned address. It works because every power of two has exactly one bit set in its binary representation. For example, the numbers {1,2,4,8,…} are {1,10,100,1000,…} in binary. By subtracting 1 we get {0,01,011,0111,…}. These binary numbers have a 1 at exactly the positions that need to be zeroed in addr. For example, the last 3 bits need to be zeroed for a alignment of 8.

To align addr, we create a bitmask from align-1. We want a 0 at the position of each 1, so we invert it using !. After that, the binary numbers look like this: {…11111,…11110,…11100,…11000,…}. Finally, we zero the correct bits using a binary AND.

Aligning upwards is simple now. We just increase addr by align-1 and call align_down. We add align-1 instead of align because we would otherwise waste align bytes for already aligned addresses.

Reusing Freed Memory

The heap memory is limited, so we should reuse freed memory for new allocations. This sounds simple, but is not so easy in practice since allocations can live arbitrarily long (and can be freed in an arbitrary order). This means that we need some kind of data structure to keep track of which memory areas are free and which are in use. This data structure should be very optimized since it causes overheads in both space (i.e. it needs backing memory) and time (i.e. accessing and organizing it needs CPU cycles).

Our bump allocator only keeps track of the next free memory address, which doesn't suffice to keep track of freed memory areas. So our only choice is to ignore deallocations and leak the corresponding memory. Thus our allocator quickly runs out of memory in a real system, but it suffices for simple testing. Later in this post, we will introduce a better allocator that does not leak freed memory.

Using it as System Allocator

Above we saw that we can use a static allocator as system allocator through the global_allocator attribute:

#[global_allocator]

static ALLOCATOR: MyAllocator = MyAllocator {...};

This requires an implementation of Alloc for &MyAllocator, i.e. a shared reference. If we try to add such an implementation for our bump allocator (unsafe impl<'a> Alloc for &'a BumpAllocator), we have a problem: Our alloc method requires updating the next field, which is not possible for a shared reference.

One solution could be to put the bump allocator behind a Mutex and wrap it into a new type, for which we can implement Alloc for a shared reference:

struct LockedBumpAllocator(Mutex<BumpAllocator>);

impl<'a> Alloc for &'a LockedBumpAllocator {

unsafe fn alloc(&mut self, layout: Layout) -> Result<*mut u8, AllocErr> {

self.0.lock().alloc(layout)

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&mut self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout) {

self.0.lock().dealloc(ptr, layout)

}

}

However, there is a more interesting solution for our bump allocator that avoids locking altogether. The idea is to exploit that we only need to update a single usize field byusing an AtomicUsize type. This type uses special synchronized hardware instructions to ensure data race freedom without requiring locks.

A lock-free Bump Allocator

A lock-free implementation looks like this:

use core::sync::atomic::{AtomicUsize, Ordering};

/// A simple allocator that allocates memory linearly and ignores freed memory.

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct BumpAllocator {

heap_start: usize,

heap_end: usize,

next: AtomicUsize,

}

impl BumpAllocator {

pub const fn new(heap_start: usize, heap_end: usize) -> Self {

// NOTE: requires adding #![feature(const_atomic_usize_new)] to lib.rs

Self { heap_start, heap_end, next: AtomicUsize::new(heap_start) }

}

}

unsafe impl<'a> Alloc for &'a BumpAllocator {

unsafe fn alloc(&mut self, layout: Layout) -> Result<*mut u8, AllocErr> {

loop {

// load current state of the `next` field

let current_next = self.next.load(Ordering::Relaxed);

let alloc_start = align_up(current_next, layout.align());

let alloc_end = alloc_start.saturating_add(layout.size());

if alloc_end <= self.heap_end {

// update the `next` pointer if it still has the value `current_next`

let next_now = self.next.compare_and_swap(current_next, alloc_end,

Ordering::Relaxed);

if next_now == current_next {

// next address was successfully updated, allocation succeeded

return Ok(alloc_start as *mut u8);

}

} else {

return Err(AllocErr::Exhausted{ request: layout })

}

}

}

unsafe fn dealloc(&mut self, ptr: *mut u8, layout: Layout) {

// do nothing, leak memory

}

}

The implementation is a bit more complicated now. First, there is now a loop around the whole method body, since we might need multiple tries until we succeed (e.g. if multiple threads try to allocate at the same time). Also, the loads operation is an explicit method call now, i.e. self.next.load(Ordering::Relaxed) instead of just self.next. The ordering parameter makes it possible to restrict the automatic instruction reordering performed by both the compiler and the CPU itself. For example, it is used when implementing locks to ensure that no write to the locked variable happens before the lock is acquired. We don't have such requirements, so we use the less restrictive Relaxed ordering.

The heart of this lock-free method is the compare_and_swap call that updates the next address:

...

let next_now = self.next.compare_and_swap(current_next, alloc_end,

Ordering::Relaxed);

if next_now == current_next {

// next address was successfully updated, allocation succeeded

return Ok(alloc_start as *mut u8);

}

...

Compare-and-swap is a special CPU instruction that updates a variable with a given value if it still contains the value we expect. If it doesn't, it means that another thread updated the value simultaneously, so we need to try again. The important feature is that this happens in a single uninteruptible operation (thus the name atomic), so no partial updates or intermediate states are possible.

In detail, compare_and_swap works by comparing next with the first argument and, in case they're equal, updates next with the second parameter (the previous value is returned). To find out whether a switch happened, we check the returned previous value of next. If it is equal to the first parameter, the values were swapped. Otherwise, we try again in the next loop iteration.

Setting the Global Allocator

Now we can define a static bump allocator, that we can set as system allocator:

pub const HEAP_START: usize = 0o_000_001_000_000_0000;

pub const HEAP_SIZE: usize = 100 * 1024; // 100 KiB

#[global_allocator]

static HEAP_ALLOCATOR: BumpAllocator = BumpAllocator::new(HEAP_START,

HEAP_START + HEAP_SIZE);

We use 0o_000_001_000_000_0000 as heap start address, which is the address starting at the second P3 entry. It doesn't really matter which address we choose here as long as it's unused. We use a heap size of 100 KiB, which should be large enough for the near future.

Putting the above in the memory::heap_allocator module would make most sense, but unfortunately there is currently a weird bug in the global allocator implementation that requires putting the global allocator in the root module. I hope it's fixed soon, but until then we need to put the above lines in src/lib.rs. For that, we need to make the memory::heap_allocator module public and add an import for BumpAllocator. We also need to add the #![feature(global_allocator)] at the top of our lib.rs, since the global_allocator attribute is still unstable.

That's it! We have successfully created and linked a custom system allocator. Now we're ready to test it.

Testing

We should be able to allocate memory on the heap now. Let's try it in our rust_main:

// in rust_main in src/lib.rs

use alloc::boxed::Box;

let heap_test = Box::new(42);

When we run it, a triple fault occurs and causes permanent rebooting. Let's try debug it using QEMU and objdump as described in the previous post:

> qemu-system-x86_64 -d int -no-reboot -cdrom build/os-x86_64.iso

…

check_exception old: 0xffffffff new 0xe

0: v=0e e=0002 i=0 cpl=0 IP=0008:0000000000102860 pc=0000000000102860

SP=0010:0000000000116af0 CR2=0000000040000000

…

Aha! It's a page fault (v=0e) and was caused by the code at 0x102860. The code tried to write (e=0002) to address 0x40000000. This address is 0o_000_001_000_000_0000 in octal, which is the HEAP_START address defined above. Of course it page-faults: We have forgotten to map the heap memory to some physical memory.

Some Refactoring

In order to map the heap cleanly, we do a bit of refactoring first. We move all memory initialization from our rust_main to a new memory::init function. Now our rust_main looks like this:

// in src/lib.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn rust_main(multiboot_information_address: usize) {

// ATTENTION: we have a very small stack and no guard page

vga_buffer::clear_screen();

println!("Hello World{}", "!");

let boot_info = unsafe {

multiboot2::load(multiboot_information_address)

};

enable_nxe_bit();

enable_write_protect_bit();

// set up guard page and map the heap pages

memory::init(boot_info);

use alloc::boxed::Box;

let heap_test = Box::new(42);

println!("It did not crash!");

loop {}

}

The memory::init function looks like this:

// in src/memory/mod.rs

use multiboot2::BootInformation;

pub fn init(boot_info: &BootInformation) {

let memory_map_tag = boot_info.memory_map_tag().expect(

"Memory map tag required");

let elf_sections_tag = boot_info.elf_sections_tag().expect(

"Elf sections tag required");

let kernel_start = elf_sections_tag.sections()

.filter(|s| s.is_allocated()).map(|s| s.addr).min().unwrap();

let kernel_end = elf_sections_tag.sections()

.filter(|s| s.is_allocated()).map(|s| s.addr + s.size).max()

.unwrap();

println!("kernel start: {:#x}, kernel end: {:#x}",

kernel_start,

kernel_end);

println!("multiboot start: {:#x}, multiboot end: {:#x}",

boot_info.start_address(),

boot_info.end_address());

let mut frame_allocator = AreaFrameAllocator::new(

kernel_start as usize, kernel_end as usize,

boot_info.start_address(), boot_info.end_address(),

memory_map_tag.memory_areas());

paging::remap_the_kernel(&mut frame_allocator, boot_info);

}

We've just moved the code to a new function. However, we've sneaked some improvements in:

- An additional

.filter(|s| s.is_allocated())in the calculation ofkernel_startandkernel_end. This ignores all sections that aren't loaded to memory (such as debug sections). Thus, the kernel end address is no longer artificially increased by such sections. - We use the

start_address()andend_address()methods ofboot_infoinstead of calculating the adresses manually. - We use the alternate

{:#x}form when printing kernel/multiboot addresses. Before, we used0x{:x}, which leads to the same result. For a complete list of these “alternate” formatting forms, check out the std::fmt documentation.

Safety

It is important that the memory::init function is called only once, because it creates a new frame allocator based on kernel and multiboot start/end. When we call it a second time, a new frame allocator is created that reassigns the same frames, even if they are already in use.

In the second call it would use an identical frame allocator to remap the kernel. The remap_the_kernel function would request a frame from the frame allocator to create a new page table. But the returned frame is already in use, since we used it to create our current page table in the first call. In order to initialize the new table, the function zeroes it. This is the point where everything breaks, since we zero our current page table. The CPU is unable to read the next instruction and throws a page fault.

So we need to ensure that memory::init can be only called once. We could mark it as unsafe, which would bring it in line with Rust's memory safety rules. However, that would just push the unsafety to the caller. The caller can still accidentally call the function twice, the only difference is that the mistake needs to happen inside unsafe blocks.

A better solution is to insert a check at the function's beginning, that panics if the function is called a second time. This approach has a small runtime cost, but we only call it once, so it's negligible. And we avoid two unsafe blocks (one at the calling site and one at the function itself), which is always good.

In order to make such checks easy, I created a small crate named once. To add it, we run cargo add once and add the following to our src/lib.rs:

// in src/lib.rs

#[macro_use]

extern crate once;

The crate provides an assert_has_not_been_called! macro (sorry for the long name :D). We can use it to fix the safety problem easily:

// in src/memory/mod.rs

pub fn init(boot_info: &BootInformation) {

assert_has_not_been_called!("memory::init must be called only once");

let memory_map_tag = ...

...

}

That's it. Now our memory::init function can only be called once. The macro works by creating a static AtomicBool named CALLED, which is initialized to false. When the macro is invoked, it checks the value of CALLED and sets it to true. If the value was already true before, the macro panics.

Mapping the Heap

Now we're ready to map the heap pages. In order to do it, we need access to the ActivePageTable or Mapper instance (see the page table and kernel remapping posts). For that we return it from the paging::remap_the_kernel function:

// in src/memory/paging/mod.rs

pub fn remap_the_kernel<A>(allocator: &mut A, boot_info: &BootInformation)

-> ActivePageTable // new

where A: FrameAllocator

{

...

println!("guard page at {:#x}", old_p4_page.start_address());

active_table // new

}

Now we have full page table access in the memory::init function. This allows us to map the heap pages to physical frames:

// in src/memory/mod.rs

pub fn init(boot_info: &BootInformation) {

...

let mut frame_allocator = ...;

// below is the new part

let mut active_table = paging::remap_the_kernel(&mut frame_allocator,

boot_info);

use self::paging::Page;

use {HEAP_START, HEAP_SIZE};

let heap_start_page = Page::containing_address(HEAP_START);

let heap_end_page = Page::containing_address(HEAP_START + HEAP_SIZE-1);

for page in Page::range_inclusive(heap_start_page, heap_end_page) {

active_table.map(page, paging::WRITABLE, &mut frame_allocator);

}

}

The Page::range_inclusive function is just a copy of the Frame::range_inclusive function:

// in src/memory/paging/mod.rs

#[derive(…, PartialEq, Eq, PartialOrd, Ord)]

pub struct Page {...}

impl Page {

...

pub fn range_inclusive(start: Page, end: Page) -> PageIter {

PageIter {

start: start,

end: end,

}

}

}

pub struct PageIter {

start: Page,

end: Page,

}

impl Iterator for PageIter {

type Item = Page;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Page> {

if self.start <= self.end {

let page = self.start;

self.start.number += 1;

Some(page)

} else {

None

}

}

}

Now we map the whole heap to physical pages. This needs some time and might introduce a noticeable delay when we increase the heap size in the future. Another drawback is that we consume a large amount of physical frames even though we might not need the whole heap space. We will fix these problems in a future post by mapping the pages lazily.

It works!

Now Box and Vec should work. For example:

// in rust_main in src/lib.rs

use alloc::boxed::Box;

let mut heap_test = Box::new(42);

*heap_test -= 15;

let heap_test2 = Box::new("hello");

println!("{:?} {:?}", heap_test, heap_test2);

let mut vec_test = vec![1,2,3,4,5,6,7];

vec_test[3] = 42;

for i in &vec_test {

print!("{} ", i);

}

We can also use all other types of the alloc crate, including:

- the reference counted pointers Rc and Arc

- the owned string type String and the format! macro

- Linked List

- the growable ring buffer VecDeque

- BinaryHeap

- BTreeMap and BTreeSet

A better Allocator

Right now, we leak every freed memory block. Thus, we run out of memory quickly, for example, by creating a new String in each iteration of a loop:

// in rust_main in src/lib.rs

for i in 0..10000 {

format!("Some String");

}

To fix this, we need to create an allocator that keeps track of freed memory blocks and reuses them if possible. This introduces some challenges:

- We need to keep track of a possibly unlimited number of freed blocks. For example, an application could allocate

none-byte sized blocks and free every second block, which createsn/2freed blocks. We can't rely on any upper bound of freed block sincencould be arbitrarily large. - We can't use any of the collections from above, since they rely on allocations themselves. (It might be possible as soon as RFC #1398 is implemented, which allows user-defined allocators for specific collection instances.)

- We need to merge adjacent freed blocks if possible. Otherwise, the freed memory is no longer usable for large allocations. We will discuss this point in more detail below.

- Our allocator should search the set of freed blocks quickly and keep fragmentation low.

Creating a List of freed Blocks

Where do we store the information about an unlimited number of freed blocks? We can't use any fixed size data structure since it could always be too small for some allocation sequences. So we need some kind of dynamically growing set.

One possible solution could be to use an array-like data structure that starts at some unused virtual address. If the array becomes full, we increase its size and map new physical frames as backing storage. This approach would require a large part of the virtual address space since the array could grow significantly. We would need to create a custom implementation of a growable array and manipulate the page tables when deallocating. It would also consume a possibly large number of physical frames as backing storage.

We will choose another solution with different tradoffs. It's not clearly “better” than the approach above and has significant disadvantages itself. However, it has one big advantage: It does not need any additional physical or virtual memory at all. This makes it less complex since we don't need to manipulate any page tables. The idea is the following:

A freed memory block is not used anymore and no one needs the stored information. It is still mapped to a virtual address and backed by a physical page. So we just store the information about the freed block in the block itself. We keep a pointer to the first block and store a pointer to the next block in each block. Thus, we create a single linked list:

In the following, we call a freed block a hole. Each hole stores its size and a pointer to the next hole. If a hole is larger than needed, we leave the remaining memory unused. By storing a pointer to the first hole, we are able to traverse the complete list.

Initialization

When the heap is created, all of its memory is unused. Thus, it forms a single large hole:

The optional pointer to the next hole is set to None.

Allocation

In order to allocate a block of memory, we need to find a hole that satisfies the size and alignment requirements. If the found hole is larger than required, we split it into two smaller holes. For example, when we allocate a 24 byte block right after initialization, we split the single hole into a hole of size 24 and a hole with the remaining size:

Then we use the new 24 byte hole to perform the allocation:

To find a suitable hole, we can use several search strategies:

- best fit: Search the whole list and choose the smallest hole that satisfies the requirements.

- worst fit: Search the whole list and choose the largest hole that satisfies the requirements.

- first fit: Search the list from the beginning and choose the first hole that satisfies the requirements.

Each strategy has its advantages and disadvantages. Best fit uses the smallest hole possible and leaves larger holes for large allocations. But splitting the smallest hole might create a tiny hole, which is too small for most allocations. In contrast, the worst fit strategy always chooses the largest hole. Thus, it does not create tiny holes, but it consumes the large block, which might be required for large allocations.

For our use case, the best fit strategy is better than worst fit. The reason is that we have a minimal hole size of 16 bytes, since each hole needs to be able to store a size (8 bytes) and a pointer to the next hole (8 bytes). Thus, even the best fit strategy leads to holes of usable size. Furthermore, we will need to allocate very large blocks occasionally (e.g. for DMA buffers).

However, both best fit and worst fit have a significant problem: They need to scan the whole list for each allocation in order to find the optimal block. This leads to long allocation times if the list is long. The first fit strategy does not have this problem, as it returns as soon as it finds a suitable hole. It is fairly fast for small allocations and might only need to scan the whole list for large allocations.

Deallocation

To deallocate a block of memory, we can just insert its corresponding hole somewhere into the list. However, we need to merge adjacent holes. Otherwise, we are unable to reuse the freed memory for larger allocations. For example:

In order to use these adjacent holes for a large allocation, we need to merge them to a single large hole first:

The easiest way to ensure that adjacent holes are always merged, is to keep the hole list sorted by address. Thus, we only need to check the predecessor and the successor in the list when we free a memory block. If they are adjacent to the freed block, we merge the corresponding holes. Else, we insert the freed block as a new hole at the correct position.

Implementation

The detailed implementation would go beyond the scope of this post, since it contains several hidden difficulties. For example:

- Several merge cases: Merge with the previous hole, merge with the next hole, merge with both holes.

- We need to satisfy the alignment requirements, which requires additional splitting logic.

- The minimal hole size of 16 bytes: We must not create smaller holes when splitting a hole.

I created the linked_list_allocator crate to handle all of these cases. It consists of a Heap struct that provides an allocate_first_fit and a deallocate method. It also contains a LockedHeap type that wraps Heap into spinlock so that it's usable as a static system allocator. If you are interested in the implementation details, check out the source code.

We need to add the extern crate to our Cargo.toml and our lib.rs:

> cargo add linked_list_allocator

// in src/lib.rs

extern crate linked_list_allocator;

Now we can change our global allocator:

use linked_list_allocator::LockedHeap;

#[global_allocator]

static HEAP_ALLOCATOR: LockedHeap = LockedHeap::empty();

We can't initialize the linked list allocator statically, since it needs to initialize the first hole (like described above). This can't be done at compile time, so the function can't be a const function. Therefore we can only create an empty heap and initialize it later at runtime. For that, we add the following lines to our rust_main function:

// in src/lib.rs

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn rust_main(multiboot_information_address: usize) {

[…]

// set up guard page and map the heap pages

memory::init(boot_info);

// initialize the heap allocator

unsafe {

HEAP_ALLOCATOR.lock().init(HEAP_START, HEAP_START + HEAP_SIZE);

}

[…]

}

It is important that we initialize the heap after mapping the heap pages, since the init function writes to the heap memory (the first hole).

Our kernel uses the new allocator now, so we can deallocate memory without leaking it. The example from above should work now without causing an OOM situation:

// in rust_main in src/lib.rs

for i in 0..10000 {

format!("Some String");

}

Performance

The linked list based approach has some performance problems. Each allocation or deallocation might need to scan the complete list of holes in the worst case. However, I think it's good enough for now, since our heap will stay relatively small for the near future. When our allocator becomes a performance problem eventually, we can just replace it with a faster alternative.

Summary

Now we're able to use heap storage in our kernel without leaking memory. This allows us to effectively process dynamic data such as user supplied strings in the future. We can also use Rc and Arc to create types with shared ownership. And we have access to various data structures such as Vec or Linked List, which will make our lives much easier. We even have some well tested and optimized binary heap and B-tree implementations!

TODO: update date