mirror of

https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os.git

synced 2025-12-17 06:47:49 +00:00

Rename second-edition subfolder to `edition-2

This commit is contained in:

@@ -1,702 +0,0 @@

|

||||

+++

|

||||

title = "حالت متن VGA"

|

||||

weight = 3

|

||||

path = "fa/vga-text-mode"

|

||||

date = 2018-02-26

|

||||

|

||||

[extra]

|

||||

chapter = "Bare Bones"

|

||||

# Please update this when updating the translation

|

||||

translation_based_on_commit = "fb8b03e82d9805473fed16e8795a78a020a6b537"

|

||||

# GitHub usernames of the people that translated this post

|

||||

translators = ["hamidrezakp", "MHBahrampour"]

|

||||

rtl = true

|

||||

+++

|

||||

|

||||

[حالت متن VGA] یک روش ساده برای چاپ متن روی صفحه است. در این پست ، با قرار دادن همه موارد غیر ایمنی در یک ماژول جداگانه ، رابطی ایجاد می کنیم که استفاده از آن را ایمن و ساده می کند. همچنین پشتیبانی از [ماکروی فرمتبندی] راست را پیاده سازی میکنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[حالت متن VGA]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VGA-compatible_text_mode

|

||||

[ماکروی فرمتبندی]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/fmt/#related-macros

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- more -->

|

||||

|

||||

این بلاگ بصورت آزاد بر روی [گیتهاب] توسعه داده شده. اگر مشکل یا سوالی دارید، لطفا آنجا یک ایشو باز کنید. همچنین میتوانید [در زیر] این پست کامنت بگذارید. سورس کد کامل این پست را می توانید در شاخه [`post-01`][post branch] پیدا کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

[گیتهاب]: https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os

|

||||

[در زیر]: #comments

|

||||

[post branch]: https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os/tree/post-03

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- toc -->

|

||||

|

||||

## بافر متن VGA

|

||||

برای چاپ یک کاراکتر روی صفحه در حالت متن VGA ، باید آن را در بافر متن سخت افزار VGA بنویسید. بافر متن VGA یک آرایه دو بعدی است که به طور معمول 25 ردیف و 80 ستون دارد که مستقیماً به صفحه نمایش داده(رندر) می شود. هر خانه آرایه یک کاراکتر صفحه نمایش را از طریق قالب زیر توصیف می کند:

|

||||

|

||||

Bit(s) | Value

|

||||

------ | ----------------

|

||||

0-7 | ASCII code point

|

||||

8-11 | Foreground color

|

||||

12-14 | Background color

|

||||

15 | Blink

|

||||

|

||||

اولین بایت کاراکتری در [کدگذاری ASCII] را نشان می دهد که باید چاپ شود. اگر بخواهیم دقیق باشیم ، دقیقاً ASCII نیست ، بلکه مجموعه ای از کاراکترها به نام [_کد صفحه 437_] با برخی کاراکتر های اضافی و تغییرات جزئی است. برای سادگی ، ما در این پست آنرا یک کاراکتر ASCII می نامیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[کدگذاری ASCII]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ASCII

|

||||

[_کد صفحه 437_]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_page_437

|

||||

|

||||

بایت دوم نحوه نمایش کاراکتر را مشخص می کند. چهار بیت اول رنگ پیش زمینه را مشخص می کند ، سه بیت بعدی رنگ پس زمینه و بیت آخر اینکه کاراکتر باید چشمک بزند یا نه. رنگ های زیر موجود است:

|

||||

|

||||

Number | Color | Number + Bright Bit | Bright Color

|

||||

------ | ---------- | ------------------- | -------------

|

||||

0x0 | Black | 0x8 | Dark Gray

|

||||

0x1 | Blue | 0x9 | Light Blue

|

||||

0x2 | Green | 0xa | Light Green

|

||||

0x3 | Cyan | 0xb | Light Cyan

|

||||

0x4 | Red | 0xc | Light Red

|

||||

0x5 | Magenta | 0xd | Pink

|

||||

0x6 | Brown | 0xe | Yellow

|

||||

0x7 | Light Gray | 0xf | White

|

||||

|

||||

بیت 4، بیت روشنایی است ، که به عنوان مثال آبی به آبی روشن تبدیل میکند. برای رنگ پس زمینه ، این بیت به عنوان بیت چشمک مورد استفاده قرار می گیرد.

|

||||

|

||||

بافر متن VGA از طریق [ورودی/خروجی حافظهنگاشتی] به آدرس`0xb8000` قابل دسترسی است. این بدان معنی است که خواندن و نوشتن در آن آدرس به RAM دسترسی ندارد ، بلکه مستقیماً دسترسی به بافر متن در سخت افزار VGA دارد. این بدان معنی است که می توانیم آن را از طریق عملیات حافظه عادی در آن آدرس بخوانیم و بنویسیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[ورودی/خروجی حافظهنگاشتی]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memory-mapped_I/O

|

||||

|

||||

توجه داشته باشید که ممکن است سخت افزار حافظهنگاشتی شده از تمام عملیات معمول RAM پشتیبانی نکند. به عنوان مثال ، یک دستگاه ممکن است فقط خواندن بایتی را پشتیبانی کرده و با خواندن `u64` یک مقدار زباله را برگرداند. خوشبختانه بافر متن [از خواندن و نوشتن عادی پشتیبانی می کند] ، بنابراین مجبور نیستیم با آن به روش خاصی برخورد کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[از خواندن و نوشتن عادی پشتیبانی می کند]: https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs140/projects/pintos/specs/freevga/vga/vgamem.htm#manip

|

||||

|

||||

## یک ماژول راست

|

||||

اکنون که از نحوه کار بافر VGA مطلع شدیم ، می توانیم یک ماژول Rust برای مدیریت چاپ ایجاد کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/main.rs

|

||||

mod vga_buffer;

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

برای محتوای این ماژول ما یک فایل جدید `src/vga_buffer.rs` ایجاد می کنیم. همه کدهای زیر وارد ماژول جدید ما می شوند (مگر اینکه طور دیگری مشخص شده باشد).

|

||||

|

||||

### رنگ ها

|

||||

اول ، ما رنگ های مختلف را با استفاده از یک enum نشان می دهیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[allow(dead_code)]

|

||||

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

|

||||

#[repr(u8)]

|

||||

pub enum Color {

|

||||

Black = 0,

|

||||

Blue = 1,

|

||||

Green = 2,

|

||||

Cyan = 3,

|

||||

Red = 4,

|

||||

Magenta = 5,

|

||||

Brown = 6,

|

||||

LightGray = 7,

|

||||

DarkGray = 8,

|

||||

LightBlue = 9,

|

||||

LightGreen = 10,

|

||||

LightCyan = 11,

|

||||

LightRed = 12,

|

||||

Pink = 13,

|

||||

Yellow = 14,

|

||||

White = 15,

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

ما در اینجا از [enum مانند C] برای مشخص کردن صریح عدد برای هر رنگ استفاده می کنیم. به دلیل ویژگی `repr(u8)` هر نوع enum به عنوان یک `u8` ذخیره می شود. در واقع 4 بیت کافی است ، اما Rust نوع `u4` ندارد.

|

||||

|

||||

[enum مانند C]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/custom_types/enum/c_like.html

|

||||

|

||||

به طور معمول کامپایلر برای هر نوع استفاده نشده اخطار می دهد. با استفاده از ویژگی `#[allow(dead_code)]` این هشدارها را برای enum `Color` غیرفعال می کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

توسط [deriving] کردن تریتهای [`Copy`], [`Clone`], [`Debug`], [`PartialEq`], و [`Eq`] ما [مفهوم کپی] را برای نوع فعال کرده و آن را قابل پرینت کردن میکنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[deriving]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/trait/derive.html

|

||||

[`Copy`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/marker/trait.Copy.html

|

||||

[`Clone`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/clone/trait.Clone.html

|

||||

[`Debug`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/fmt/trait.Debug.html

|

||||

[`PartialEq`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/cmp/trait.PartialEq.html

|

||||

[`Eq`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/cmp/trait.Eq.html

|

||||

[مفهوم کپی]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/1.30.0/book/first-edition/ownership.html#copy-types

|

||||

|

||||

برای نشان دادن یک کد کامل رنگ که رنگ پیش زمینه و پس زمینه را مشخص می کند ، یک [نوع جدید] بر روی `u8` ایجاد می کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

[نوع جدید]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/generics/new_types.html

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

|

||||

#[repr(transparent)]

|

||||

struct ColorCode(u8);

|

||||

|

||||

impl ColorCode {

|

||||

fn new(foreground: Color, background: Color) -> ColorCode {

|

||||

ColorCode((background as u8) << 4 | (foreground as u8))

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

ساختمان `ColorCode` شامل بایت کامل رنگ است که شامل رنگ پیش زمینه و پس زمینه است. مانند قبل ، ویژگی های `Copy` و` Debug` را برای آن derive می کنیم. برای اطمینان از اینکه `ColorCode` دقیقاً ساختار داده مشابه `u8` دارد ، از ویژگی [`repr(transparent)`] استفاده می کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[`repr(transparent)`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nomicon/other-reprs.html#reprtransparent

|

||||

|

||||

### بافر متن

|

||||

اکنون می توانیم ساختمانهایی را برای نمایش یک کاراکتر صفحه و بافر متن اضافه کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

|

||||

#[repr(C)]

|

||||

struct ScreenChar {

|

||||

ascii_character: u8,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode,

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

const BUFFER_HEIGHT: usize = 25;

|

||||

const BUFFER_WIDTH: usize = 80;

|

||||

|

||||

#[repr(transparent)]

|

||||

struct Buffer {

|

||||

chars: [[ScreenChar; BUFFER_WIDTH]; BUFFER_HEIGHT],

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

از آنجا که ترتیب فیلدهای ساختمانهای پیش فرض در Rust تعریف نشده است ، به ویژگی[`repr(C)`] نیاز داریم. این تضمین می کند که فیلد های ساختمان دقیقاً مانند یک ساختمان C ترسیم شده اند و بنابراین ترتیب درست را تضمین می کند. برای ساختمان `Buffer` ، ما دوباره از [`repr(transparent)`] استفاده می کنیم تا اطمینان حاصل شود که نحوه قرارگیری در حافظه دقیقا همان یک فیلد است.

|

||||

|

||||

[`repr(C)`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/nomicon/other-reprs.html#reprc

|

||||

|

||||

برای نوشتن در صفحه ، اکنون یک نوع نویسنده ایجاد می کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

pub struct Writer {

|

||||

column_position: usize,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode,

|

||||

buffer: &'static mut Buffer,

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

نویسنده همیشه در آخرین خط مینویسد و وقتی خط پر است (یا در `\n`) ، سطرها را به سمت بالا شیفت می دهد. فیلد `column_position` موقعیت فعلی در ردیف آخر را نگهداری می کند. رنگهای پیش زمینه و پس زمینه فعلی توسط `color_code` مشخص شده و یک ارجاع (رفرنس) به بافر VGA در `buffer` ذخیره می شود. توجه داشته باشید که ما در اینجا به [طول عمر مشخصی] نیاز داریم تا به کامپایلر بگوییم تا چه مدت این ارجاع معتبر است. ظول عمر [`'static`] مشخص می کند که ارجاع برای کل مدت زمان اجرای برنامه معتبر باشد (که برای بافر متن VGA درست است).

|

||||

|

||||

[طول عمر مشخصی]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch10-03-lifetime-syntax.html#lifetime-annotation-syntax

|

||||

[`'static`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch10-03-lifetime-syntax.html#the-static-lifetime

|

||||

|

||||

### چاپ کردن

|

||||

اکنون می توانیم از `Writer` برای تغییر کاراکترهای بافر استفاده کنیم. ابتدا یک متد برای نوشتن یک بایت ASCII ایجاد می کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

pub fn write_byte(&mut self, byte: u8) {

|

||||

match byte {

|

||||

b'\n' => self.new_line(),

|

||||

byte => {

|

||||

if self.column_position >= BUFFER_WIDTH {

|

||||

self.new_line();

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

let row = BUFFER_HEIGHT - 1;

|

||||

let col = self.column_position;

|

||||

|

||||

let color_code = self.color_code;

|

||||

self.buffer.chars[row][col] = ScreenChar {

|

||||

ascii_character: byte,

|

||||

color_code,

|

||||

};

|

||||

self.column_position += 1;

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

fn new_line(&mut self) {/* TODO */}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

اگر بایت، بایتِ [خط جدید] `\n` باشد، نویسنده چیزی چاپ نمی کند. در عوض متد `new_line` را فراخوانی می کند که بعداً آن را پیادهسازی خواهیم کرد. بایت های دیگر در حالت دوم match روی صفحه چاپ می شوند.

|

||||

|

||||

[خط جدید]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newline

|

||||

|

||||

هنگام چاپ بایت ، نویسنده بررسی می کند که آیا خط فعلی پر است یا نه. در صورت پُر بودن، برای نوشتن در خط ، باید متد `new_line` صدا زده شود. سپس یک `ScreenChar` جدید در بافر در موقعیت فعلی می نویسد. سرانجام ، موقعیت ستون فعلی یکی افزایش مییابد.

|

||||

|

||||

برای چاپ کل رشته ها، می توانیم آنها را به بایت تبدیل کرده و یکی یکی چاپ کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

pub fn write_string(&mut self, s: &str) {

|

||||

for byte in s.bytes() {

|

||||

match byte {

|

||||

// printable ASCII byte or newline

|

||||

0x20..=0x7e | b'\n' => self.write_byte(byte),

|

||||

// not part of printable ASCII range

|

||||

_ => self.write_byte(0xfe),

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

بافر متن VGA فقط از ASCII و بایت های اضافی [کد صفحه 437] پشتیبانی می کند. رشته های راست به طور پیش فرض [UTF-8] هستند ، بنابراین ممکن است حاوی بایت هایی باشند که توسط بافر متن VGA پشتیبانی نمی شوند. ما از یک match برای تفکیک بایت های قابل چاپ ASCII (یک خط جدید یا هر چیز دیگری بین یک کاراکتر فاصله و یک کاراکتر`~`) و بایت های غیر قابل چاپ استفاده می کنیم. برای بایت های غیر قابل چاپ ، یک کاراکتر `■` چاپ می کنیم که دارای کد شانزدهای (hex) `0xfe` بر روی سخت افزار VGA است.

|

||||

|

||||

[کد صفحه 437]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_page_437

|

||||

[UTF-8]: https://www.fileformat.info/info/unicode/utf8.htm

|

||||

|

||||

#### امتحاناش کنید!

|

||||

برای نوشتن چند کاراکتر بر روی صفحه ، می توانید یک تابع موقتی ایجاد کنید:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

pub fn print_something() {

|

||||

let mut writer = Writer {

|

||||

column_position: 0,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

};

|

||||

|

||||

writer.write_byte(b'H');

|

||||

writer.write_string("ello ");

|

||||

writer.write_string("Wörld!");

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

ابتدا یک Writer جدید ایجاد می کند که به بافر VGA در `0xb8000` اشاره دارد. سینتکس این ممکن است کمی عجیب به نظر برسد: اول ، ما عدد صحیح `0xb8000` را به عنوان [اشاره گر خام] قابل تغییر در نظر می گیریم. سپس با dereferencing کردن آن (از طریق "*") و بلافاصله ارجاع مجدد (از طریق `&mut`) آن را به یک مرجع قابل تغییر تبدیل می کنیم. این تبدیل به یک [بلوک `غیرایمن`] احتیاج دارد ، زیرا کامپایلر نمی تواند صحت اشارهگر خام را تضمین کند.

|

||||

|

||||

[اشاره گر خام]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch19-01-unsafe-rust.html#dereferencing-a-raw-pointer

|

||||

[بلوک `غیرایمن`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch19-01-unsafe-rust.html

|

||||

|

||||

سپس بایت `b'H'` را روی آن می نویسد. پیشوند `b` یک [بایت لیترال] ایجاد می کند ، که بیانگر یک کاراکتر ASCII است. با نوشتن رشته های `"ello "` و `"Wörld!"` ، ما متد `write_string` و واکنش به کاراکترهای غیر قابل چاپ را آزمایش می کنیم. برای دیدن خروجی ، باید تابع `print_something` را از تابع `_start` فراخوانی کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/main.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[no_mangle]

|

||||

pub extern "C" fn _start() -> ! {

|

||||

vga_buffer::print_something();

|

||||

|

||||

loop {}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

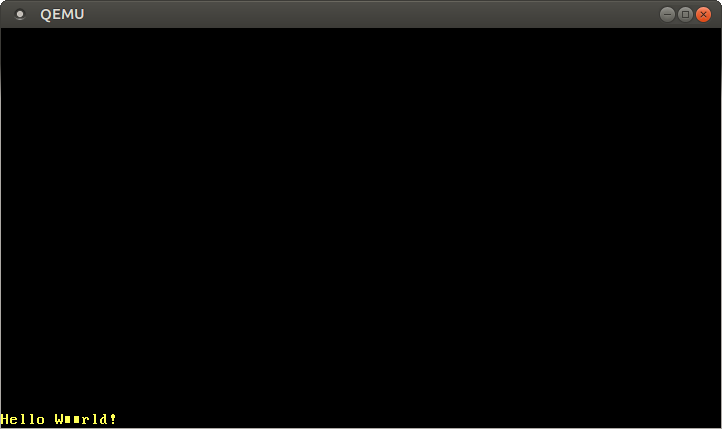

اکنون هنگامی که ما پروژه را اجرا می کنیم ، باید یک `Hello W■■rld!` در گوشه سمت چپ _پایین_ صفحه به رنگ زرد چاپ شود:

|

||||

|

||||

[بایت لیترال]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/tokens.html#byte-literals

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

توجه داشته باشید که `ö` به عنوان دو کاراکتر `■` چاپ شده است. به این دلیل که `ö` با دو بایت در [UTF-8] نمایش داده می شود ، که هر دو در محدوده قابل چاپ ASCII قرار نمی گیرند. در حقیقت ، این یک ویژگی اساسی UTF-8 است: هر بایت از مقادیر چند بایتی هرگز ASCII معتبر نیستند.

|

||||

|

||||

### فرّار

|

||||

ما الان دیدیم که پیام ما به درستی چاپ شده است. با این حال ، ممکن است با کامپایلرهای آینده Rust که به صورت تهاجمی تری(aggressively) بهینه می شوند ، کار نکند.

|

||||

|

||||

مشکل این است که ما فقط به `Buffer` می نویسیم و هرگز از آن نمیخوانیم. کامپایلر نمی داند که ما واقعاً به حافظه بافر VGA (به جای RAM معمولی) دسترسی پیدا می کنیم و در مورد اثر جانبی آن یعنی نمایش برخی کاراکتر ها روی صفحه چیزی نمی داند. بنابراین ممکن است تصمیم بگیرد که این نوشتن ها غیرضروری هستند و می تواند آن را حذف کند. برای جلوگیری از این بهینه سازی اشتباه ، باید این نوشتن ها را به عنوان _[فرّار]_ مشخص کنیم. این به کامپایلر می گوید که نوشتن عوارض جانبی دارد و نباید بهینه شود.

|

||||

|

||||

[فرّار]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volatile_(computer_programming)

|

||||

|

||||

به منظور استفاده از نوشتن های فرار برای بافر VGA ، ما از کتابخانه [volatile][volatile crate] استفاده می کنیم. این _crate_ (بسته ها در جهان Rust اینطور نامیده میشوند) نوع `Volatile` را که یک نوع wrapper هست با متد های `read` و `write` فراهم می کند. این متد ها به طور داخلی از توابع [read_volatile] و [write_volatile] کتابخانه اصلی استفاده می کنند و بنابراین تضمین می کنند که خواندن/ نوشتن با بهینه شدن حذف نمیشوند.

|

||||

|

||||

[volatile crate]: https://docs.rs/volatile

|

||||

[read_volatile]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/ptr/fn.read_volatile.html

|

||||

[write_volatile]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/ptr/fn.write_volatile.html

|

||||

|

||||

ما می توانیم وابستگی به کرت (crate) `volatile` را بوسیله اضافه کردن آن به بخش `dependencies` (وابستگی های) `Cargo.toml` اضافه کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in Cargo.toml

|

||||

|

||||

[dependencies]

|

||||

volatile = "0.2.6"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

`0.2.6` شماره نسخه [معنایی] است. برای اطلاعات بیشتر ، به راهنمای [تعیین وابستگی ها] مستندات کارگو (cargo) مراجعه کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

[معنایی]: https://semver.org/

|

||||

[تعیین وابستگی ها]: https://doc.crates.io/specifying-dependencies.html

|

||||

|

||||

بیایید از آن برای نوشتن فرار در بافر VGA استفاده کنیم. نوع `Buffer` خود را به صورت زیر بروزرسانی می کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

use volatile::Volatile;

|

||||

|

||||

struct Buffer {

|

||||

chars: [[Volatile<ScreenChar>; BUFFER_WIDTH]; BUFFER_HEIGHT],

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

به جای `ScreenChar` ، ما اکنون از `Volatile<ScreenChar>` استفاده می کنیم. (نوع `Volatile`، [generic] است و می تواند (تقریباً) هر نوع را در خود قرار دهد). این اطمینان می دهد که ما به طور تصادفی نمی توانیم از طریق نوشتن "عادی" در آن بنویسیم. در عوض ، اکنون باید از متد `write` استفاده کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[generic]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch10-01-syntax.html

|

||||

|

||||

این بدان معنی است که ما باید متد `Writer::write_byte` خود را به روز کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

pub fn write_byte(&mut self, byte: u8) {

|

||||

match byte {

|

||||

b'\n' => self.new_line(),

|

||||

byte => {

|

||||

...

|

||||

|

||||

self.buffer.chars[row][col].write(ScreenChar {

|

||||

ascii_character: byte,

|

||||

color_code,

|

||||

});

|

||||

...

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

...

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

به جای انتساب عادی با استفاده از `=` ، اکنون ما از متد `write` استفاده می کنیم. این تضمین می کند که کامپایلر هرگز این نوشتن را بهینه نخواهد کرد.

|

||||

|

||||

### ماکروهای قالببندی

|

||||

خوب است که از ماکروهای قالب بندی Rust نیز پشتیبانی کنید. به این ترتیب ، می توانیم انواع مختلفی مانند عدد صحیح یا شناور را به راحتی چاپ کنیم. برای پشتیبانی از آنها ، باید تریت [`core::fmt::Write`] را پیاده سازی کنیم. تنها متد مورد نیاز این تریت ،`write_str` است که کاملاً شبیه به متد `write_str` ما است ، فقط با نوع بازگشت `fmt::Result`:

|

||||

|

||||

[`core::fmt::Write`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/fmt/trait.Write.html

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

use core::fmt;

|

||||

|

||||

impl fmt::Write for Writer {

|

||||

fn write_str(&mut self, s: &str) -> fmt::Result {

|

||||

self.write_string(s);

|

||||

Ok(())

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

`Ok(())` فقط نتیجه `Ok` حاوی نوع `()` است.

|

||||

|

||||

اکنون ما می توانیم از ماکروهای قالب بندی داخلی راست یعنی `write!`/`writeln!` استفاده کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

pub fn print_something() {

|

||||

use core::fmt::Write;

|

||||

let mut writer = Writer {

|

||||

column_position: 0,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

};

|

||||

|

||||

writer.write_byte(b'H');

|

||||

writer.write_string("ello! ");

|

||||

write!(writer, "The numbers are {} and {}", 42, 1.0/3.0).unwrap();

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

حالا شما باید یک `Hello! The numbers are 42 and 0.3333333333333333` در پایین صفحه ببینید. فراخوانی `write!` یک `Result` را برمی گرداند که در صورت عدم استفاده باعث هشدار می شود ، بنابراین ما تابع [`unwrap`] را روی آن فراخوانی می کنیم که در صورت بروز خطا پنیک می کند. این در مورد ما مشکلی ندارد ، زیرا نوشتن در بافر VGA هرگز شکست نمیخورد.

|

||||

|

||||

[`unwrap`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/core/result/enum.Result.html#method.unwrap

|

||||

|

||||

### خطوط جدید

|

||||

در حال حاضر ، ما از خطوط جدید و کاراکتر هایی که دیگر در خط نمی گنجند چشم پوشی می کنیم. درعوض ما می خواهیم هر کاراکتر را یک خط به بالا منتقل کنیم (خط بالا حذف می شود) و دوباره از ابتدای آخرین خط شروع کنیم. برای انجام این کار ، ما یک پیاده سازی برای متد `new_line` در `Writer` اضافه می کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

fn new_line(&mut self) {

|

||||

for row in 1..BUFFER_HEIGHT {

|

||||

for col in 0..BUFFER_WIDTH {

|

||||

let character = self.buffer.chars[row][col].read();

|

||||

self.buffer.chars[row - 1][col].write(character);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

self.clear_row(BUFFER_HEIGHT - 1);

|

||||

self.column_position = 0;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

fn clear_row(&mut self, row: usize) {/* TODO */}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

ما تمام کاراکترهای صفحه را پیمایش می کنیم و هر کاراکتر را یک ردیف به بالا شیفت می دهیم. توجه داشته باشید که علامت گذاری دامنه (`..`) فاقد مقدار حد بالا است. ما همچنین سطر 0 را حذف می کنیم (اول محدوده از "1" شروع می شود) زیرا این سطر است که از صفحه به بیرون شیفت می شود.

|

||||

|

||||

برای تکمیل کد `newline` ، متد `clear_row` را اضافه می کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

fn clear_row(&mut self, row: usize) {

|

||||

let blank = ScreenChar {

|

||||

ascii_character: b' ',

|

||||

color_code: self.color_code,

|

||||

};

|

||||

for col in 0..BUFFER_WIDTH {

|

||||

self.buffer.chars[row][col].write(blank);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

این متد با جایگزینی تمام کاراکترها با یک کاراکتر فاصله ، یک سطر را پاک می کند.

|

||||

|

||||

## یک رابط گلوبال

|

||||

برای فراهم کردن یک نویسنده گلوبال که بتواند به عنوان رابط از سایر ماژول ها بدون حمل نمونه `Writer` در اطراف استفاده شود ، سعی می کنیم یک `WRITER` ثابت ایجاد کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

pub static WRITER: Writer = Writer {

|

||||

column_position: 0,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

};

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

با این حال ، اگر سعی کنیم اکنون آن را کامپایل کنیم ، خطاهای زیر رخ می دهد:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

error[E0015]: calls in statics are limited to constant functions, tuple structs and tuple variants

|

||||

--> src/vga_buffer.rs:7:17

|

||||

|

|

||||

7 | color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

|

||||

|

||||

error[E0396]: raw pointers cannot be dereferenced in statics

|

||||

--> src/vga_buffer.rs:8:22

|

||||

|

|

||||

8 | buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ dereference of raw pointer in constant

|

||||

|

||||

error[E0017]: references in statics may only refer to immutable values

|

||||

--> src/vga_buffer.rs:8:22

|

||||

|

|

||||

8 | buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ statics require immutable values

|

||||

|

||||

error[E0017]: references in statics may only refer to immutable values

|

||||

--> src/vga_buffer.rs:8:13

|

||||

|

|

||||

8 | buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ statics require immutable values

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

برای فهمیدن آنچه در اینجا اتفاق می افتد ، باید بدانیم که ثابت ها(Statics) در زمان کامپایل مقداردهی اولیه می شوند ، برخلاف متغیرهای عادی که در زمان اجرا مقداردهی اولیه می شوند. مولفهای(component) از کامپایلر Rust که چنین عبارات مقداردهی اولیه را ارزیابی می کند ، “[const evaluator]” نامیده می شود. عملکرد آن هنوز محدود است ، اما کارهای گسترده ای برای گسترش آن در حال انجام است ، به عنوان مثال در “[Allow panicking in constants]” RFC.

|

||||

|

||||

[const evaluator]: https://rustc-dev-guide.rust-lang.org/const-eval.html

|

||||

[Allow panicking in constants]: https://github.com/rust-lang/rfcs/pull/2345

|

||||

|

||||

مسئله در مورد `ColorCode::new` با استفاده از توابع [`const` functions] قابل حل است ، اما مشکل اساسی اینجاست که Rust's const evaluator قادر به تبدیل اشارهگرهای خام به رفرنس در زمان کامپایل نیست. شاید روزی جواب دهد ، اما تا آن زمان ، ما باید راه حل دیگری پیدا کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[`const` functions]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/unstable-book/language-features/const-fn.html

|

||||

|

||||

### استاتیکهای تنبل (Lazy Statics)

|

||||

یکبار مقداردهی اولیه استاتیکها با توابع غیر ثابت یک مشکل رایج در راست است. خوشبختانه ، در حال حاضر راه حل خوبی در کرتی به نام [lazy_static] وجود دارد. این کرت ماکرو `lazy_static!` را فراهم می کند که یک `استاتیک` را با تنبلی مقداردهی اولیه می کند. به جای محاسبه مقدار آن در زمان کامپایل ، `استاتیک` به تنبلی هنگام اولین دسترسی به آن، خود را مقداردهی اولیه میکند. بنابراین ، مقداردهی اولیه در زمان اجرا اتفاق می افتد تا کد مقدار دهی اولیه پیچیده و دلخواه امکان پذیر باشد.

|

||||

|

||||

[lazy_static]: https://docs.rs/lazy_static/1.0.1/lazy_static/

|

||||

|

||||

بیایید کرت `lazy_static` را به پروژه خود اضافه کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in Cargo.toml

|

||||

|

||||

[dependencies.lazy_static]

|

||||

version = "1.0"

|

||||

features = ["spin_no_std"]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

ما به ویژگی `spin_no_std` نیاز داریم ، زیرا به کتابخانه استاندارد پیوند نمی دهیم.

|

||||

|

||||

با استفاده از `lazy_static` ، می توانیم WRITER ثابت خود را بدون مشکل تعریف کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

use lazy_static::lazy_static;

|

||||

|

||||

lazy_static! {

|

||||

pub static ref WRITER: Writer = Writer {

|

||||

column_position: 0,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

};

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

با این حال ، این `WRITER` بسیار بی فایده است زیرا غیر قابل تغییر است. این بدان معنی است که ما نمی توانیم چیزی در آن بنویسیم (از آنجا که همه متد های نوشتن `&mut self` را در ورودی میگیرند). یک راه حل ممکن استفاده از [استاتیک قابل تغییر] است. اما پس از آن هر خواندن و نوشتن آن ناامن (unsafe) است زیرا می تواند به راحتی باعث data race و سایر موارد بد باشد. استفاده از `static mut` بسیار نهی شده است ، حتی پیشنهادهایی برای [حذف آن][remove static mut] وجود داشت. اما گزینه های دیگر چیست؟ ما می توانیم سعی کنیم از یک استاتیک تغییرناپذیر با نوع سلول مانند [RefCell] یا حتی [UnsafeCell] استفاده کنیم که [تغییر پذیری داخلی] را فراهم می کند. اما این انواع [Sync] نیستند (با دلیل کافی) ، بنابراین نمی توانیم از آنها در استاتیک استفاده کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[استاتیک قابل تغییر]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch19-01-unsafe-rust.html#accessing-or-modifying-a-mutable-static-variable

|

||||

[remove static mut]: https://internals.rust-lang.org/t/pre-rfc-remove-static-mut/1437

|

||||

[RefCell]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch15-05-interior-mutability.html#keeping-track-of-borrows-at-runtime-with-refcellt

|

||||

[UnsafeCell]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/cell/struct.UnsafeCell.html

|

||||

[تغییر پذیری داخلی]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch15-05-interior-mutability.html

|

||||

[Sync]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/marker/trait.Sync.html

|

||||

|

||||

### Spinlocks

|

||||

برای دستیابی به قابلیت تغییرپذیری داخلی همزمان (synchronized) ، کاربران کتابخانه استاندارد می توانند از [Mutex] استفاده کنند. هنگامی که منبع از قبل قفل شده است ، با مسدود کردن رشته ها ، امکان انحصار متقابل را فراهم می کند. اما هسته اصلی ما هیچ پشتیبانی از مسدود کردن یا حتی مفهومی از نخ ها ندارد ، بنابراین ما هم نمی توانیم از آن استفاده کنیم. با این وجود یک نوع کاملاً پایهای از mutex در علوم کامپیوتر وجود دارد که به هیچ ویژگی سیستم عاملی نیاز ندارد: [spinlock]. به جای مسدود کردن ، نخ ها سعی می کنند آن را بارها و بارها در یک حلقه قفل کنند و بنابراین زمان پردازنده را می سوزانند تا دوباره mutex آزاد شود.

|

||||

|

||||

[Mutex]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/std/sync/struct.Mutex.html

|

||||

[spinlock]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spinlock

|

||||

|

||||

برای استفاده از spinning mutex ، می توانیم [کرت spin] را به عنوان یک وابستگی اضافه کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

[کرت spin]: https://crates.io/crates/spin

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in Cargo.toml

|

||||

[dependencies]

|

||||

spin = "0.5.2"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

سپس می توانیم از spinning Mutex برای افزودن [تغییر پذیری داخلی] امن به `WRITER` استاتیک خود استفاده کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

use spin::Mutex;

|

||||

...

|

||||

lazy_static! {

|

||||

pub static ref WRITER: Mutex<Writer> = Mutex::new(Writer {

|

||||

column_position: 0,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

});

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

اکنون می توانیم تابع `print_something` را حذف کرده و مستقیماً از تابع`_start` خود چاپ کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/main.rs

|

||||

#[no_mangle]

|

||||

pub extern "C" fn _start() -> ! {

|

||||

use core::fmt::Write;

|

||||

vga_buffer::WRITER.lock().write_str("Hello again").unwrap();

|

||||

write!(vga_buffer::WRITER.lock(), ", some numbers: {} {}", 42, 1.337).unwrap();

|

||||

|

||||

loop {}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

برای اینکه بتوانیم از توابع آن استفاده کنیم ، باید تریت `fmt::Write` را وارد کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

### ایمنی

|

||||

توجه داشته باشید که ما فقط یک بلوک ناامن در کد خود داریم که برای ایجاد رفرنس `Buffer` با اشاره به `0xb8000` لازم است. پس از آن ، تمام عملیات ایمن هستند. Rust به طور پیش فرض از بررسی مرزها در دسترسی به آرایه استفاده می کند ، بنابراین نمی توانیم به طور اتفاقی خارج از بافر بنویسیم. بنابراین ، ما شرایط مورد نیاز را در سیستم نوع انجام میدهیم و قادر به ایجاد یک رابط ایمن به خارج هستیم.

|

||||

|

||||

### یک ماکروی println

|

||||

اکنون که یک نویسنده گلوبال داریم ، می توانیم یک ماکرو `println` اضافه کنیم که می تواند از هر کجا در کد استفاده شود. [سینتکس ماکروی] راست کمی عجیب است ، بنابراین ما سعی نمی کنیم ماکرو را از ابتدا بنویسیم. در عوض به سورس [ماکروی `println!`] در کتابخانه استاندارد نگاه می کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

[سینتکس ماکروی]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/book/ch19-06-macros.html#declarative-macros-with-macro_rules-for-general-metaprogramming

|

||||

[ماکروی `println!`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/std/macro.println!.html

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

#[macro_export]

|

||||

macro_rules! println {

|

||||

() => (print!("\n"));

|

||||

($($arg:tt)*) => (print!("{}\n", format_args!($($arg)*)));

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

ماکروها از طریق یک یا چند قانون تعریف می شوند که شبیه بازوهای `match` هستند. ماکرو `println` دارای دو قانون است: اولین قانون برای فراخوانی های بدون آرگمان است (به عنوان مثال: `println!()`) ، که به `print!("\n")` گسترش می یابد، بنابراین فقط یک خط جدید را چاپ می کند. قانون دوم برای فراخوانی هایی با پارامترهایی مانند `println!("Hello")` یا `println!("Number: {}", 4)` است. همچنین با فراخوانی کل آرگومان ها و یک خط جدید `\n` اضافی در انتها ، به فراخوانی ماکرو `print!` گسترش می یابد.

|

||||

|

||||

ویژگی `#[macro_export]` ماکرو را برای کل کرت (نه فقط ماژولی که تعریف شده است) و کرت های خارجی در دسترس قرار می دهد. همچنین ماکرو را در ریشه کرت قرار می دهد ، به این معنی که ما باید ماکرو را به جای `std::macros::println` از طریق `use std::println` وارد کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[ماکرو `print!`] به این صورت تعریف می شود:

|

||||

|

||||

[ماکرو `print!`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/std/macro.print!.html

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

#[macro_export]

|

||||

macro_rules! print {

|

||||

($($arg:tt)*) => ($crate::io::_print(format_args!($($arg)*)));

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

ماکرو به فراخوانی [تابع `_print`] در ماژول `io` گسترش می یابد. [متغیر `$crate`] تضمین می کند که ماکرو هنگام گسترش در `std` در زمان استفاده در کرت های دیگر، در خارج از کرت `std` نیز کار می کند.

|

||||

|

||||

[ماکرو `format_args`] از آرگمان های داده شده یک نوع [fmt::Arguments] را می سازد که به `_print` ارسال می شود. [تابع `_print`] از کتابخانه استاندارد،`print_to` را فراخوانی می کند ، که بسیار پیچیده است زیرا از دستگاه های مختلف `Stdout` پشتیبانی می کند. ما به این پیچیدگی احتیاج نداریم زیرا فقط می خواهیم در بافر VGA چاپ کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

[تابع `_print`]: https://github.com/rust-lang/rust/blob/29f5c699b11a6a148f097f82eaa05202f8799bbc/src/libstd/io/stdio.rs#L698

|

||||

[متغیر `$crate`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/1.30.0/book/first-edition/macros.html#the-variable-crate

|

||||

[ماکرو `format_args`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/std/macro.format_args.html

|

||||

[fmt::Arguments]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/fmt/struct.Arguments.html

|

||||

|

||||

برای چاپ در بافر VGA ، ما فقط ماکروهای `println!` و `print!` را کپی می کنیم ، اما آنها را اصلاح می کنیم تا از تابع `_print` خود استفاده کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[macro_export]

|

||||

macro_rules! print {

|

||||

($($arg:tt)*) => ($crate::vga_buffer::_print(format_args!($($arg)*)));

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

#[macro_export]

|

||||

macro_rules! println {

|

||||

() => ($crate::print!("\n"));

|

||||

($($arg:tt)*) => ($crate::print!("{}\n", format_args!($($arg)*)));

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

#[doc(hidden)]

|

||||

pub fn _print(args: fmt::Arguments) {

|

||||

use core::fmt::Write;

|

||||

WRITER.lock().write_fmt(args).unwrap();

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

چیزی که ما از تعریف اصلی `println` تغییر دادیم این است که فراخوانی ماکرو `print!` را با پیشوند `$crate` انجام می دهیم. این تضمین می کند که اگر فقط می خواهیم از `println` استفاده کنیم ، نیازی به وارد کردن ماکرو `print!` هم نداشته باشیم.

|

||||

|

||||

مانند کتابخانه استاندارد ، ویژگی `#[macro_export]` را به هر دو ماکرو اضافه می کنیم تا در همه جای کرت ما در دسترس باشند. توجه داشته باشید که این ماکروها را در فضای نام ریشه کرت قرار می دهد ، بنابراین وارد کردن آنها از طریق `use crate::vga_buffer::println` کار نمی کند. در عوض ، ما باید `use crate::println` را استفاده کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

تابع `_print` نویسنده (`WRITER`) استاتیک ما را قفل می کند و متد`write_fmt` را روی آن فراخوانی می کند. این متد از تریت `Write` است ، ما باید این تریت را وارد کنیم. اگر چاپ موفقیت آمیز نباشد ، `unwrap()` اضافی در انتها باعث پنیک میشود. اما از آنجا که ما همیشه `Ok` را در `write_str` برمی گردانیم ، این اتفاق نمی افتد.

|

||||

|

||||

از آنجا که ماکروها باید بتوانند از خارج از ماژول، `_print` را فراخوانی کنند، تابع باید عمومی (public) باشد. با این حال ، از آنجا که این جزئیات پیاده سازی را خصوصی (private) در نظر می گیریم، [ویژگی `doc(hidden)`] را اضافه می کنیم تا از مستندات تولید شده پنهان شود.

|

||||

|

||||

[ویژگی `doc(hidden)`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/rustdoc/the-doc-attribute.html#dochidden

|

||||

|

||||

### Hello World توسط `println`

|

||||

اکنون می توانیم از `println` در تابع `_start` استفاده کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/main.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[no_mangle]

|

||||

pub extern "C" fn _start() {

|

||||

println!("Hello World{}", "!");

|

||||

|

||||

loop {}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

توجه داشته باشید که ما مجبور نیستیم ماکرو را در تابع اصلی وارد کنیم ، زیرا در حال حاضر در فضای نام ریشه موجود است.

|

||||

|

||||

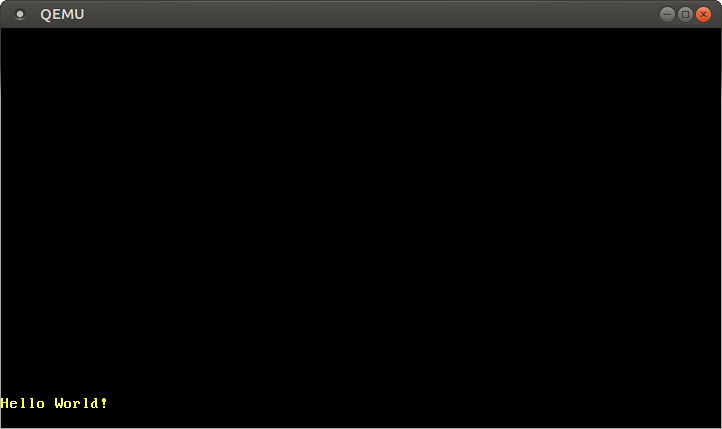

همانطور که انتظار می رفت ، اکنون یک _“Hello World!”_ روی صفحه مشاهده می کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### چاپ پیام های پنیک

|

||||

|

||||

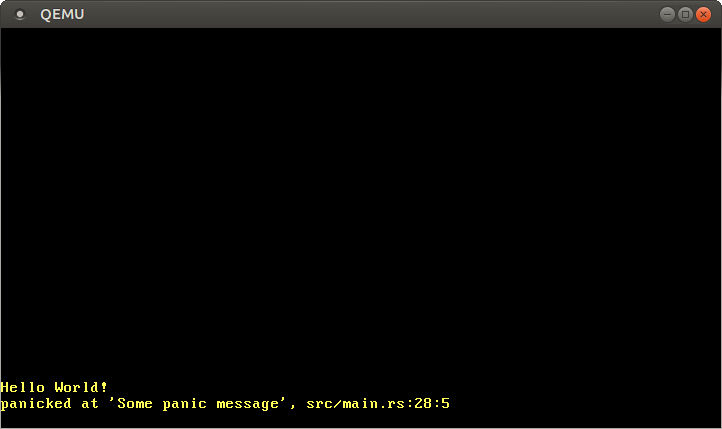

اکنون که ماکرو `println` را داریم ، می توانیم از آن در تابع پنیک برای چاپ پیام و مکان پنیک استفاده کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in main.rs

|

||||

|

||||

/// This function is called on panic.

|

||||

#[panic_handler]

|

||||

fn panic(info: &PanicInfo) -> ! {

|

||||

println!("{}", info);

|

||||

loop {}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

اکنون وقتی که `panic!("Some panic message");` را در تابع `_start` خود اضافه میکنیم ، خروجی زیر را می گیریم:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

بنابراین ما نه تنها میدانیم که یک پنیک رخ داده است ، بلکه پیام پنیک و اینکه در کجای کد رخ داده است را نیز میدانیم.

|

||||

|

||||

## خلاصه

|

||||

در این پست با ساختار بافر متن VGA و نحوه نوشتن آن از طریق نگاشت حافظه در آدرس `0xb8000` آشنا شدیم. ما یک ماژول راست ایجاد کردیم که عدم امنیت نوشتن را در این بافر نگاشت حافظه شده را محصور می کند و یک رابط امن و راحت به خارج ارائه می دهد.

|

||||

|

||||

همچنین دیدیم که به لطف کارگو ، اضافه کردن وابستگی به کتابخانه های دیگران چقدر آسان است. دو وابستگی که اضافه کردیم ، `lazy_static` و`spin` ، در توسعه سیستم عامل بسیار مفید هستند و ما در پست های بعدی از آنها در مکان های بیشتری استفاده خواهیم کرد.

|

||||

|

||||

## بعدی چیست؟

|

||||

در پست بعدی نحوه راه اندازی چارچوب تست واحد (Unit Test) راست توضیح داده شده است. سپس از این پست چند تست واحد اساسی برای ماژول بافر VGA ایجاد خواهیم کرد.

|

||||

@@ -1,697 +0,0 @@

|

||||

+++

|

||||

title = "VGA Text Mode"

|

||||

weight = 3

|

||||

path = "vga-text-mode"

|

||||

date = 2018-02-26

|

||||

|

||||

[extra]

|

||||

chapter = "Bare Bones"

|

||||

+++

|

||||

|

||||

The [VGA text mode] is a simple way to print text to the screen. In this post, we create an interface that makes its usage safe and simple, by encapsulating all unsafety in a separate module. We also implement support for Rust's [formatting macros].

|

||||

|

||||

[VGA text mode]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VGA-compatible_text_mode

|

||||

[formatting macros]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/fmt/#related-macros

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- more -->

|

||||

|

||||

This blog is openly developed on [GitHub]. If you have any problems or questions, please open an issue there. You can also leave comments [at the bottom]. The complete source code for this post can be found in the [`post-03`][post branch] branch.

|

||||

|

||||

[GitHub]: https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os

|

||||

[at the bottom]: #comments

|

||||

[post branch]: https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os/tree/post-03

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- toc -->

|

||||

|

||||

## The VGA Text Buffer

|

||||

To print a character to the screen in VGA text mode, one has to write it to the text buffer of the VGA hardware. The VGA text buffer is a two-dimensional array with typically 25 rows and 80 columns, which is directly rendered to the screen. Each array entry describes a single screen character through the following format:

|

||||

|

||||

Bit(s) | Value

|

||||

------ | ----------------

|

||||

0-7 | ASCII code point

|

||||

8-11 | Foreground color

|

||||

12-14 | Background color

|

||||

15 | Blink

|

||||

|

||||

The first byte represents the character that should be printed in the [ASCII encoding]. To be exact, it isn't exactly ASCII, but a character set named [_code page 437_] with some additional characters and slight modifications. For simplicity, we proceed to call it an ASCII character in this post.

|

||||

|

||||

[ASCII encoding]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ASCII

|

||||

[_code page 437_]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_page_437

|

||||

|

||||

The second byte defines how the character is displayed. The first four bits define the foreground color, the next three bits the background color, and the last bit whether the character should blink. The following colors are available:

|

||||

|

||||

Number | Color | Number + Bright Bit | Bright Color

|

||||

------ | ---------- | ------------------- | -------------

|

||||

0x0 | Black | 0x8 | Dark Gray

|

||||

0x1 | Blue | 0x9 | Light Blue

|

||||

0x2 | Green | 0xa | Light Green

|

||||

0x3 | Cyan | 0xb | Light Cyan

|

||||

0x4 | Red | 0xc | Light Red

|

||||

0x5 | Magenta | 0xd | Pink

|

||||

0x6 | Brown | 0xe | Yellow

|

||||

0x7 | Light Gray | 0xf | White

|

||||

|

||||

Bit 4 is the _bright bit_, which turns for example blue into light blue. For the background color, this bit is repurposed as the blink bit.

|

||||

|

||||

The VGA text buffer is accessible via [memory-mapped I/O] to the address `0xb8000`. This means that reads and writes to that address don't access the RAM, but directly the text buffer on the VGA hardware. This means that we can read and write it through normal memory operations to that address.

|

||||

|

||||

[memory-mapped I/O]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memory-mapped_I/O

|

||||

|

||||

Note that memory-mapped hardware might not support all normal RAM operations. For example, a device could only support byte-wise reads and return junk when an `u64` is read. Fortunately, the text buffer [supports normal reads and writes], so that we don't have to treat it in special way.

|

||||

|

||||

[supports normal reads and writes]: https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs140/projects/pintos/specs/freevga/vga/vgamem.htm#manip

|

||||

|

||||

## A Rust Module

|

||||

Now that we know how the VGA buffer works, we can create a Rust module to handle printing:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/main.rs

|

||||

mod vga_buffer;

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

For the content of this module we create a new `src/vga_buffer.rs` file. All of the code below goes into our new module (unless specified otherwise).

|

||||

|

||||

### Colors

|

||||

First, we represent the different colors using an enum:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[allow(dead_code)]

|

||||

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

|

||||

#[repr(u8)]

|

||||

pub enum Color {

|

||||

Black = 0,

|

||||

Blue = 1,

|

||||

Green = 2,

|

||||

Cyan = 3,

|

||||

Red = 4,

|

||||

Magenta = 5,

|

||||

Brown = 6,

|

||||

LightGray = 7,

|

||||

DarkGray = 8,

|

||||

LightBlue = 9,

|

||||

LightGreen = 10,

|

||||

LightCyan = 11,

|

||||

LightRed = 12,

|

||||

Pink = 13,

|

||||

Yellow = 14,

|

||||

White = 15,

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

We use a [C-like enum] here to explicitly specify the number for each color. Because of the `repr(u8)` attribute each enum variant is stored as an `u8`. Actually 4 bits would be sufficient, but Rust doesn't have an `u4` type.

|

||||

|

||||

[C-like enum]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/custom_types/enum/c_like.html

|

||||

|

||||

Normally the compiler would issue a warning for each unused variant. By using the `#[allow(dead_code)]` attribute we disable these warnings for the `Color` enum.

|

||||

|

||||

By [deriving] the [`Copy`], [`Clone`], [`Debug`], [`PartialEq`], and [`Eq`] traits, we enable [copy semantics] for the type and make it printable and comparable.

|

||||

|

||||

[deriving]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/trait/derive.html

|

||||

[`Copy`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/marker/trait.Copy.html

|

||||

[`Clone`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/clone/trait.Clone.html

|

||||

[`Debug`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/fmt/trait.Debug.html

|

||||

[`PartialEq`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/cmp/trait.PartialEq.html

|

||||

[`Eq`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/cmp/trait.Eq.html

|

||||

[copy semantics]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/1.30.0/book/first-edition/ownership.html#copy-types

|

||||

|

||||

To represent a full color code that specifies foreground and background color, we create a [newtype] on top of `u8`:

|

||||

|

||||

[newtype]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/generics/new_types.html

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

|

||||

#[repr(transparent)]

|

||||

struct ColorCode(u8);

|

||||

|

||||

impl ColorCode {

|

||||

fn new(foreground: Color, background: Color) -> ColorCode {

|

||||

ColorCode((background as u8) << 4 | (foreground as u8))

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

The `ColorCode` struct contains the full color byte, containing foreground and background color. Like before, we derive the `Copy` and `Debug` traits for it. To ensure that the `ColorCode` has the exact same data layout as an `u8`, we use the [`repr(transparent)`] attribute.

|

||||

|

||||

[`repr(transparent)`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nomicon/other-reprs.html#reprtransparent

|

||||

|

||||

### Text Buffer

|

||||

Now we can add structures to represent a screen character and the text buffer:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq)]

|

||||

#[repr(C)]

|

||||

struct ScreenChar {

|

||||

ascii_character: u8,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode,

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

const BUFFER_HEIGHT: usize = 25;

|

||||

const BUFFER_WIDTH: usize = 80;

|

||||

|

||||

#[repr(transparent)]

|

||||

struct Buffer {

|

||||

chars: [[ScreenChar; BUFFER_WIDTH]; BUFFER_HEIGHT],

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

Since the field ordering in default structs is undefined in Rust, we need the [`repr(C)`] attribute. It guarantees that the struct's fields are laid out exactly like in a C struct and thus guarantees the correct field ordering. For the `Buffer` struct, we use [`repr(transparent)`] again to ensure that it has the same memory layout as its single field.

|

||||

|

||||

[`repr(C)`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/nomicon/other-reprs.html#reprc

|

||||

|

||||

To actually write to screen, we now create a writer type:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

pub struct Writer {

|

||||

column_position: usize,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode,

|

||||

buffer: &'static mut Buffer,

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

The writer will always write to the last line and shift lines up when a line is full (or on `\n`). The `column_position` field keeps track of the current position in the last row. The current foreground and background colors are specified by `color_code` and a reference to the VGA buffer is stored in `buffer`. Note that we need an [explicit lifetime] here to tell the compiler how long the reference is valid. The [`'static`] lifetime specifies that the reference is valid for the whole program run time (which is true for the VGA text buffer).

|

||||

|

||||

[explicit lifetime]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch10-03-lifetime-syntax.html#lifetime-annotation-syntax

|

||||

[`'static`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch10-03-lifetime-syntax.html#the-static-lifetime

|

||||

|

||||

### Printing

|

||||

Now we can use the `Writer` to modify the buffer's characters. First we create a method to write a single ASCII byte:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

pub fn write_byte(&mut self, byte: u8) {

|

||||

match byte {

|

||||

b'\n' => self.new_line(),

|

||||

byte => {

|

||||

if self.column_position >= BUFFER_WIDTH {

|

||||

self.new_line();

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

let row = BUFFER_HEIGHT - 1;

|

||||

let col = self.column_position;

|

||||

|

||||

let color_code = self.color_code;

|

||||

self.buffer.chars[row][col] = ScreenChar {

|

||||

ascii_character: byte,

|

||||

color_code,

|

||||

};

|

||||

self.column_position += 1;

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

fn new_line(&mut self) {/* TODO */}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

If the byte is the [newline] byte `\n`, the writer does not print anything. Instead it calls a `new_line` method, which we'll implement later. Other bytes get printed to the screen in the second match case.

|

||||

|

||||

[newline]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newline

|

||||

|

||||

When printing a byte, the writer checks if the current line is full. In that case, a `new_line` call is required before to wrap the line. Then it writes a new `ScreenChar` to the buffer at the current position. Finally, the current column position is advanced.

|

||||

|

||||

To print whole strings, we can convert them to bytes and print them one-by-one:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

pub fn write_string(&mut self, s: &str) {

|

||||

for byte in s.bytes() {

|

||||

match byte {

|

||||

// printable ASCII byte or newline

|

||||

0x20..=0x7e | b'\n' => self.write_byte(byte),

|

||||

// not part of printable ASCII range

|

||||

_ => self.write_byte(0xfe),

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The VGA text buffer only supports ASCII and the additional bytes of [code page 437]. Rust strings are [UTF-8] by default, so they might contain bytes that are not supported by the VGA text buffer. We use a match to differentiate printable ASCII bytes (a newline or anything in between a space character and a `~` character) and unprintable bytes. For unprintable bytes, we print a `■` character, which has the hex code `0xfe` on the VGA hardware.

|

||||

|

||||

[code page 437]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_page_437

|

||||

[UTF-8]: https://www.fileformat.info/info/unicode/utf8.htm

|

||||

|

||||

#### Try it out!

|

||||

To write some characters to the screen, you can create a temporary function:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

pub fn print_something() {

|

||||

let mut writer = Writer {

|

||||

column_position: 0,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

};

|

||||

|

||||

writer.write_byte(b'H');

|

||||

writer.write_string("ello ");

|

||||

writer.write_string("Wörld!");

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

It first creates a new Writer that points to the VGA buffer at `0xb8000`. The syntax for this might seem a bit strange: First, we cast the integer `0xb8000` as an mutable [raw pointer]. Then we convert it to a mutable reference by dereferencing it (through `*`) and immediately borrowing it again (through `&mut`). This conversion requires an [`unsafe` block], since the compiler can't guarantee that the raw pointer is valid.

|

||||

|

||||

[raw pointer]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch19-01-unsafe-rust.html#dereferencing-a-raw-pointer

|

||||

[`unsafe` block]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch19-01-unsafe-rust.html

|

||||

|

||||

Then it writes the byte `b'H'` to it. The `b` prefix creates a [byte literal], which represents an ASCII character. By writing the strings `"ello "` and `"Wörld!"`, we test our `write_string` method and the handling of unprintable characters. To see the output, we need to call the `print_something` function from our `_start` function:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/main.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#[no_mangle]

|

||||

pub extern "C" fn _start() -> ! {

|

||||

vga_buffer::print_something();

|

||||

|

||||

loop {}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

When we run our project now, a `Hello W■■rld!` should be printed in the _lower_ left corner of the screen in yellow:

|

||||

|

||||

[byte literal]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/tokens.html#byte-literals

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Notice that the `ö` is printed as two `■` characters. That's because `ö` is represented by two bytes in [UTF-8], which both don't fall into the printable ASCII range. In fact, this is a fundamental property of UTF-8: the individual bytes of multi-byte values are never valid ASCII.

|

||||

|

||||

### Volatile

|

||||

We just saw that our message was printed correctly. However, it might not work with future Rust compilers that optimize more aggressively.

|

||||

|

||||

The problem is that we only write to the `Buffer` and never read from it again. The compiler doesn't know that we really access VGA buffer memory (instead of normal RAM) and knows nothing about the side effect that some characters appear on the screen. So it might decide that these writes are unnecessary and can be omitted. To avoid this erroneous optimization, we need to specify these writes as _[volatile]_. This tells the compiler that the write has side effects and should not be optimized away.

|

||||

|

||||

[volatile]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volatile_(computer_programming)

|

||||

|

||||

In order to use volatile writes for the VGA buffer, we use the [volatile][volatile crate] library. This _crate_ (this is how packages are called in the Rust world) provides a `Volatile` wrapper type with `read` and `write` methods. These methods internally use the [read_volatile] and [write_volatile] functions of the core library and thus guarantee that the reads/writes are not optimized away.

|

||||

|

||||

[volatile crate]: https://docs.rs/volatile

|

||||

[read_volatile]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/ptr/fn.read_volatile.html

|

||||

[write_volatile]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/ptr/fn.write_volatile.html

|

||||

|

||||

We can add a dependency on the `volatile` crate by adding it to the `dependencies` section of our `Cargo.toml`:

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in Cargo.toml

|

||||

|

||||

[dependencies]

|

||||

volatile = "0.2.6"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The `0.2.6` is the [semantic] version number. For more information, see the [Specifying Dependencies] guide of the cargo documentation.

|

||||

|

||||

[semantic]: https://semver.org/

|

||||

[Specifying Dependencies]: https://doc.crates.io/specifying-dependencies.html

|

||||

|

||||

Let's use it to make writes to the VGA buffer volatile. We update our `Buffer` type as follows:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

use volatile::Volatile;

|

||||

|

||||

struct Buffer {

|

||||

chars: [[Volatile<ScreenChar>; BUFFER_WIDTH]; BUFFER_HEIGHT],

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

Instead of a `ScreenChar`, we're now using a `Volatile<ScreenChar>`. (The `Volatile` type is [generic] and can wrap (almost) any type). This ensures that we can't accidentally write to it through a “normal” write. Instead, we have to use the `write` method now.

|

||||

|

||||

[generic]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch10-01-syntax.html

|

||||

|

||||

This means that we have to update our `Writer::write_byte` method:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

pub fn write_byte(&mut self, byte: u8) {

|

||||

match byte {

|

||||

b'\n' => self.new_line(),

|

||||

byte => {

|

||||

...

|

||||

|

||||

self.buffer.chars[row][col].write(ScreenChar {

|

||||

ascii_character: byte,

|

||||

color_code,

|

||||

});

|

||||

...

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

...

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Instead of a normal assignment using `=`, we're now using the `write` method. This guarantees that the compiler will never optimize away this write.

|

||||

|

||||

### Formatting Macros

|

||||

It would be nice to support Rust's formatting macros, too. That way, we can easily print different types like integers or floats. To support them, we need to implement the [`core::fmt::Write`] trait. The only required method of this trait is `write_str` that looks quite similar to our `write_string` method, just with a `fmt::Result` return type:

|

||||

|

||||

[`core::fmt::Write`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/fmt/trait.Write.html

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

use core::fmt;

|

||||

|

||||

impl fmt::Write for Writer {

|

||||

fn write_str(&mut self, s: &str) -> fmt::Result {

|

||||

self.write_string(s);

|

||||

Ok(())

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

The `Ok(())` is just a `Ok` Result containing the `()` type.

|

||||

|

||||

Now we can use Rust's built-in `write!`/`writeln!` formatting macros:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

pub fn print_something() {

|

||||

use core::fmt::Write;

|

||||

let mut writer = Writer {

|

||||

column_position: 0,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

};

|

||||

|

||||

writer.write_byte(b'H');

|

||||

writer.write_string("ello! ");

|

||||

write!(writer, "The numbers are {} and {}", 42, 1.0/3.0).unwrap();

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Now you should see a `Hello! The numbers are 42 and 0.3333333333333333` at the bottom of the screen. The `write!` call returns a `Result` which causes a warning if not used, so we call the [`unwrap`] function on it, which panics if an error occurs. This isn't a problem in our case, since writes to the VGA buffer never fail.

|

||||

|

||||

[`unwrap`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/core/result/enum.Result.html#method.unwrap

|

||||

|

||||

### Newlines

|

||||

Right now, we just ignore newlines and characters that don't fit into the line anymore. Instead we want to move every character one line up (the top line gets deleted) and start at the beginning of the last line again. To do this, we add an implementation for the `new_line` method of `Writer`:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

fn new_line(&mut self) {

|

||||

for row in 1..BUFFER_HEIGHT {

|

||||

for col in 0..BUFFER_WIDTH {

|

||||

let character = self.buffer.chars[row][col].read();

|

||||

self.buffer.chars[row - 1][col].write(character);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

self.clear_row(BUFFER_HEIGHT - 1);

|

||||

self.column_position = 0;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

fn clear_row(&mut self, row: usize) {/* TODO */}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

We iterate over all screen characters and move each character one row up. Note that the range notation (`..`) is exclusive the upper bound. We also omit the 0th row (the first range starts at `1`) because it's the row that is shifted off screen.

|

||||

|

||||

To finish the newline code, we add the `clear_row` method:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

impl Writer {

|

||||

fn clear_row(&mut self, row: usize) {

|

||||

let blank = ScreenChar {

|

||||

ascii_character: b' ',

|

||||

color_code: self.color_code,

|

||||

};

|

||||

for col in 0..BUFFER_WIDTH {

|

||||

self.buffer.chars[row][col].write(blank);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

This method clears a row by overwriting all of its characters with a space character.

|

||||

|

||||

## A Global Interface

|

||||

To provide a global writer that can be used as an interface from other modules without carrying a `Writer` instance around, we try to create a static `WRITER`:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// in src/vga_buffer.rs

|

||||

|

||||

pub static WRITER: Writer = Writer {

|

||||

column_position: 0,

|

||||

color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

};

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

However, if we try to compile it now, the following errors occur:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

error[E0015]: calls in statics are limited to constant functions, tuple structs and tuple variants

|

||||

--> src/vga_buffer.rs:7:17

|

||||

|

|

||||

7 | color_code: ColorCode::new(Color::Yellow, Color::Black),

|

||||

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

|

||||

|

||||

error[E0396]: raw pointers cannot be dereferenced in statics

|

||||

--> src/vga_buffer.rs:8:22

|

||||

|

|

||||

8 | buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ dereference of raw pointer in constant

|

||||

|

||||

error[E0017]: references in statics may only refer to immutable values

|

||||

--> src/vga_buffer.rs:8:22

|

||||

|

|

||||

8 | buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ statics require immutable values

|

||||

|

||||

error[E0017]: references in statics may only refer to immutable values

|

||||

--> src/vga_buffer.rs:8:13

|

||||

|

|

||||

8 | buffer: unsafe { &mut *(0xb8000 as *mut Buffer) },

|

||||

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ statics require immutable values

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

To understand what's happening here, we need to know that statics are initialized at compile time, in contrast to normal variables that are initialized at run time. The component of the Rust compiler that evaluates such initialization expressions is called the “[const evaluator]”. Its functionality is still limited, but there is ongoing work to expand it, for example in the “[Allow panicking in constants]” RFC.

|

||||

|

||||

[const evaluator]: https://rustc-dev-guide.rust-lang.org/const-eval.html

|

||||

[Allow panicking in constants]: https://github.com/rust-lang/rfcs/pull/2345

|

||||

|

||||

The issue about `ColorCode::new` would be solvable by using [`const` functions], but the fundamental problem here is that Rust's const evaluator is not able to convert raw pointers to references at compile time. Maybe it will work someday, but until then, we have to find another solution.

|

||||

|

||||