mirror of

https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os.git

synced 2025-12-17 23:07:50 +00:00

Rename second-edition subfolder to `edition-2

This commit is contained in:

@@ -0,0 +1,6 @@

|

||||

+++

|

||||

title = "Extra Posts for Minimal Rust Kernel"

|

||||

sort_by = "weight"

|

||||

insert_anchor_links = "left"

|

||||

render = false

|

||||

+++

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,29 @@

|

||||

+++

|

||||

title = "Disable the Red Zone"

|

||||

weight = 1

|

||||

path = "red-zone"

|

||||

template = "edition-2/extra.html"

|

||||

+++

|

||||

|

||||

The [red zone] is an optimization of the [System V ABI] that allows functions to temporarily use the 128 bytes below its stack frame without adjusting the stack pointer:

|

||||

|

||||

[red zone]: https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2011/09/06/stack-frame-layout-on-x86-64#the-red-zone

|

||||

[System V ABI]: https://wiki.osdev.org/System_V_ABI

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- more -->

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The image shows the stack frame of a function with `n` local variables. On function entry, the stack pointer is adjusted to make room on the stack for the return address and the local variables.

|

||||

|

||||

The red zone is defined as the 128 bytes below the adjusted stack pointer. The function can use this area for temporary data that's not needed across function calls. Thus, the two instructions for adjusting the stack pointer can be avoided in some cases (e.g. in small leaf functions).

|

||||

|

||||

However, this optimization leads to huge problems with exceptions or hardware interrupts. Let's assume that an exception occurs while a function uses the red zone:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The CPU and the exception handler overwrite the data in red zone. But this data is still needed by the interrupted function. So the function won't work correctly anymore when we return from the exception handler. This might lead to strange bugs that [take weeks to debug].

|

||||

|

||||

[take weeks to debug]: https://forum.osdev.org/viewtopic.php?t=21720

|

||||

|

||||

To avoid such bugs when we implement exception handling in the future, we disable the red zone right from the beginning. This is achieved by adding the `"disable-redzone": true` line to our target configuration file.

|

||||

@@ -0,0 +1,92 @@

|

||||

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

|

||||

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.0//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/2001/PR-SVG-20010719/DTD/svg10.dtd">

|

||||

<svg width="17cm" height="11cm" viewBox="-60 -21 340 212" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink">

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03111" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="90" y="65.9389">

|

||||

<tspan x="90" y="65.9389"></tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="204" y1="70" x2="176.236" y2="70"/>

|

||||

<polyline style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" points="185.118,65 175.118,70 185.118,75 "/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="7.90222" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="208" y="72.75">

|

||||

<tspan x="208" y="72.75">Old Stack Pointer</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<text font-size="7.90222" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="75" y="230">

|

||||

<tspan x="75" y="230"></tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="-20" y1="70" x2="-4" y2="70"/>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="-20" y1="190" x2="-4" y2="190"/>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #000000" x1="-12" y1="72.2361" x2="-12" y2="187.764"/>

|

||||

<polyline style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" points="-7,81.118 -12,71.118 -17,81.118 "/>

|

||||

<polyline style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" points="-17,178.882 -12,188.882 -7,178.882 "/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #000000" x1="0" y1="-20" x2="0" y2="0"/>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #000000" x1="170" y1="-20" x2="170" y2="0"/>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #00ff00" x="0" y="0" width="170" height="20"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="0" y="0" width="170" height="20"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03097" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="85" y="13.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="85" y="13.125">Return Address</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03097" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="84" y="4">

|

||||

<tspan x="84" y="4"></tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #dddddd" x="0" y="20" width="170" height="20"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="0" y="20" width="170" height="20"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03111" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="85" y="33.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="85" y="33.125">Local Variable 1</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #cccccc" x="0" y="40" width="170" height="32"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #000000" x="0" y="40" width="170" height="32"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03097" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="85" y="59.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="85" y="59.125">Local Variables 2..n</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="0" y1="40" x2="170" y2="40"/>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="0" y1="72" x2="120" y2="72"/>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #ff3333" x="0" y="70" width="170" height="120"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="0" y="70" width="170" height="120"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03111" style="fill: #ffffff;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="40" y="179.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="40" y="179.125">Red Zone</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<text font-size="7.9021" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:end;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="-20" y="132.75">

|

||||

<tspan x="-20" y="132.75">128 bytes</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #ffc200" x="30" y="70" width="140" height="30"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="30" y="70" width="140" height="30"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03097" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="100" y="88.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="100" y="88.125">Exception Stack Frame</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #ffe000" x="30" y="100" width="140" height="30"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="30" y="100" width="140" height="30"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03097" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="100" y="118.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="100" y="118.125">Register Backup</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #c6db97" x="30" y="130" width="140" height="30"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="30" y="130" width="140" height="30"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="8.46654" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="100" y="147.925">

|

||||

<tspan x="100" y="147.925">Handler Function Stack Frame</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #ff3333" x1="30" y1="70" x2="30" y2="160"/>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #ff3333" x1="30" y1="160" x2="170" y2="160"/>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="204" y1="160" x2="176.236" y2="160"/>

|

||||

<polyline style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" points="185.118,155 175.118,160 185.118,165 "/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="7.90222" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="208" y="162.635">

|

||||

<tspan x="208" y="162.635">New Stack Pointer</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

</svg>

|

||||

|

After Width: | Height: | Size: 6.2 KiB |

@@ -0,0 +1,62 @@

|

||||

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

|

||||

<!DOCTYPE svg PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD SVG 1.0//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/2001/PR-SVG-20010719/DTD/svg10.dtd">

|

||||

<svg width="14cm" height="9cm" viewBox="-60 -21 270 172" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink">

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03111" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="90" y="65.9389">

|

||||

<tspan x="90" y="65.9389"></tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="154" y1="70" x2="126.236" y2="70"/>

|

||||

<polyline style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" points="135.118,65 125.118,70 135.118,75 "/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="7.90222" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="158" y="72.75">

|

||||

<tspan x="158" y="72.75">Stack Pointer</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<text font-size="7.90222" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="75" y="230">

|

||||

<tspan x="75" y="230"></tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="-20" y1="70" x2="-4" y2="70"/>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="-20" y1="150" x2="-4" y2="150"/>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #000000" x1="-12" y1="72.2361" x2="-12" y2="147.764"/>

|

||||

<polyline style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" points="-7,81.118 -12,71.118 -17,81.118 "/>

|

||||

<polyline style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" points="-17,138.882 -12,148.882 -7,138.882 "/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #000000" x1="0" y1="-20" x2="0" y2="0"/>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #000000" x1="120" y1="-20" x2="120" y2="0"/>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #00ff00" x="0" y="0" width="120" height="20"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="0" y="0" width="120" height="20"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03097" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="60" y="13.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="60" y="13.125">Return Address</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03097" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:start;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="84" y="4">

|

||||

<tspan x="84" y="4"></tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #dddddd" x="0" y="20" width="120" height="20"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="0" y="20" width="120" height="20"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03111" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="60" y="33.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="60" y="33.125">Local Variable 1</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #cccccc" x="0" y="40" width="120" height="32"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke-dasharray: 4; stroke: #000000" x="0" y="40" width="120" height="32"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03097" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="60" y="59.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="60" y="59.125">Local Variables 2..n</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="0" y1="40" x2="120" y2="40"/>

|

||||

<line style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x1="0" y1="72" x2="120" y2="72"/>

|

||||

<g>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: #ff3333" x="0" y="70" width="120" height="80"/>

|

||||

<rect style="fill: none; fill-opacity:0; stroke-width: 1; stroke: #000000" x="0" y="70" width="120" height="80"/>

|

||||

</g>

|

||||

<text font-size="9.03111" style="fill: #ffffff;text-anchor:middle;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="60" y="113.125">

|

||||

<tspan x="60" y="113.125">Red Zone</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

<text font-size="7.9021" style="fill: #000000;text-anchor:end;font-family:sans-serif;font-style:normal;font-weight:normal" x="-20" y="112.75">

|

||||

<tspan x="-20" y="112.75">128 bytes</tspan>

|

||||

</text>

|

||||

</svg>

|

||||

|

After Width: | Height: | Size: 4.2 KiB |

@@ -0,0 +1,44 @@

|

||||

+++

|

||||

title = "Disable SIMD"

|

||||

weight = 2

|

||||

path = "disable-simd"

|

||||

template = "edition-2/extra.html"

|

||||

+++

|

||||

|

||||

[Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD)] instructions are able to perform an operation (e.g. addition) simultaneously on multiple data words, which can speed up programs significantly. The `x86_64` architecture supports various SIMD standards:

|

||||

|

||||

[Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD)]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIMD

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- more -->

|

||||

|

||||

- [MMX]: The _Multi Media Extension_ instruction set was introduced in 1997 and defines eight 64 bit registers called `mm0` through `mm7`. These registers are just aliases for the registers of the [x87 floating point unit].

|

||||

- [SSE]: The _Streaming SIMD Extensions_ instruction set was introduced in 1999. Instead of re-using the floating point registers, it adds a completely new register set. The sixteen new registers are called `xmm0` through `xmm15` and are 128 bits each.

|

||||

- [AVX]: The _Advanced Vector Extensions_ are extensions that further increase the size of the multimedia registers. The new registers are called `ymm0` through `ymm15` and are 256 bits each. They extend the `xmm` registers, so e.g. `xmm0` is the lower half of `ymm0`.

|

||||

|

||||

[MMX]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MMX_(instruction_set)

|

||||

[x87 floating point unit]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X87

|

||||

[SSE]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streaming_SIMD_Extensions

|

||||

[AVX]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Vector_Extensions

|

||||

|

||||

By using such SIMD standards, programs can often speed up significantly. Good compilers are able to transform normal loops into such SIMD code automatically through a process called [auto-vectorization].

|

||||

|

||||

[auto-vectorization]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automatic_vectorization

|

||||

|

||||

However, the large SIMD registers lead to problems in OS kernels. The reason is that the kernel has to backup all registers that it uses to memory on each hardware interrupt, because they need to have their original values when the interrupted program continues. So if the kernel uses SIMD registers, it has to backup a lot more data (512–1600 bytes), which noticeably decreases performance. To avoid this performance loss, we want to disable the `sse` and `mmx` features (the `avx` feature is disabled by default).

|

||||

|

||||

We can do that through the the `features` field in our target specification. To disable the `mmx` and `sse` features we add them prefixed with a minus:

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

"features": "-mmx,-sse"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Floating Point

|

||||

Unfortunately for us, the `x86_64` architecture uses SSE registers for floating point operations. Thus, every use of floating point with disabled SSE causes an error in LLVM. The problem is that Rust's core library already uses floats (e.g., it implements traits for `f32` and `f64`), so avoiding floats in our kernel does not suffice.

|

||||

|

||||

Fortunately, LLVM has support for a `soft-float` feature, emulates all floating point operations through software functions based on normal integers. This makes it possible to use floats in our kernel without SSE, it will just be a bit slower.

|

||||

|

||||

To turn on the `soft-float` feature for our kernel, we add it to the `features` line in our target specification, prefixed with a plus:

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

"features": "-mmx,-sse,+soft-float"

|

||||

```

|

||||

503

blog/content/edition-2/posts/02-minimal-rust-kernel/index.fa.md

Normal file

503

blog/content/edition-2/posts/02-minimal-rust-kernel/index.fa.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,503 @@

|

||||

+++

|

||||

title = "یک هسته مینیمال با Rust"

|

||||

weight = 2

|

||||

path = "fa/minimal-rust-kernel"

|

||||

date = 2018-02-10

|

||||

|

||||

[extra]

|

||||

chapter = "Bare Bones"

|

||||

# Please update this when updating the translation

|

||||

translation_based_on_commit = "7212ffaa8383122b1eb07fe1854814f99d2e1af4"

|

||||

# GitHub usernames of the people that translated this post

|

||||

translators = ["hamidrezakp", "MHBahrampour"]

|

||||

rtl = true

|

||||

+++

|

||||

|

||||

در این پست ما برای معماری x86 یک هسته مینیمال ۶۴ بیتی به زبان راست میسازیم. با استفاده از باینری مستقل Rust از پست قبل، یک دیسک ایمیج قابل بوت میسازیم، که متنی را در صفحه چاپ کند.

|

||||

|

||||

[باینری مستقل Rust]: @/edition-2/posts/01-freestanding-rust-binary/index.md

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- more -->

|

||||

|

||||

این بلاگ بصورت آزاد روی [گیتهاب] توسعه داده شده است. اگر شما مشکل یا سوالی دارید، لطفاً آنجا یک ایشو باز کنید. شما همچنین میتوانید [در زیر] این پست کامنت بگذارید. منبع کد کامل این پست را میتوانید در بِرَنچ [`post-02`][post branch] پیدا کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

[گیتهاب]: https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os

|

||||

[در زیر]: #comments

|

||||

[post branch]: https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os/tree/post-02

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- toc -->

|

||||

|

||||

## فرآیند بوت شدن

|

||||

وقتی یک رایانه را روشن میکنید، شروع به اجرای کد فِرْموِر (کلمه: firmware) ذخیره شده در [ROM] مادربرد میکند. این کد یک [power-on self-test] انجام میدهد، رم موجود را تشخیص داده، و پردازنده و سخت افزار را پیش مقداردهی اولیه میکند. پس از آن به یک دنبال دیسک قابل بوت میگردد و شروع به بوت کردن هسته سیستم عامل میکند.

|

||||

|

||||

[ROM]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Read-only_memory

|

||||

[power-on self-test]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power-on_self-test

|

||||

|

||||

در x86، دو استاندارد فِرْموِر (کلمه: firmware) وجود دارد: «سامانهٔ ورودی/خروجیِ پایه» (**[BIOS]**) و استاندارد جدیدتر «رابط فِرْموِر توسعه یافته یکپارچه» (**[UEFI]**). استاندارد BIOS قدیمی و منسوخ است، اما ساده است و از دهه ۱۹۸۰ تاکنون در هر دستگاه x86 کاملاً پشتیبانی میشود. در مقابل، UEFI مدرنتر است و ویژگیهای بسیار بیشتری دارد، اما راه اندازی آن پیچیدهتر است (حداقل به نظر من).

|

||||

|

||||

[BIOS]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BIOS

|

||||

[UEFI]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unified_Extensible_Firmware_Interface

|

||||

|

||||

در حال حاضر، ما فقط پشتیبانی BIOS را ارائه میدهیم، اما پشتیبانی از UEFI نیز برنامهریزی شده است. اگر میخواهید در این زمینه به ما کمک کنید، [ایشو گیتهاب](https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os/issues/349) را بررسی کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

### بوت شدن BIOS

|

||||

|

||||

تقریباً همه سیستمهای x86 از بوت شدن BIOS پشتیبانی میکنند، از جمله سیستمهای جدیدترِ مبتنی بر UEFI که از BIOS شبیهسازی شده استفاده میکنند. این عالی است، زیرا شما میتوانید از منطق بوت یکسانی در تمام سیستمهای قرنهای گذشته استفاده کنید. اما این سازگاری گسترده در عین حال بزرگترین نقطه ضعف راهاندازی BIOS است، زیرا این بدان معناست که پردازنده قبل از بوت شدن در یک حالت سازگاری 16 بیتی به نام [real mode] قرار داده میشود تا بوتلودرهای قدیمی از دهه 1980 همچنان کار کنند.

|

||||

|

||||

اما بیایید از ابتدا شروع کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

وقتی یک رایانه را روشن میکنید، BIOS را از حافظه فلش مخصوصی که روی مادربرد قرار دارد بارگذاری میکند. BIOS روالهای خودآزمایی و مقداردهی اولیه سخت افزار را اجرا می کند، سپس به دنبال دیسکهای قابل بوت میگردد. اگر یکی را پیدا کند، کنترل به _بوتلودرِ_ آن منتقل میشود، که یک قسمت ۵۱۲ بایتی از کد اجرایی است و در ابتدای دیسک ذخیره شده است. بیشتر بوتلودرها از ۵۱۲ بایت بزرگتر هستند، بنابراین بوتلودرها معمولاً به یک قسمت کوچک ابتدایی تقسیم میشوند که در ۵۱۲ بایت جای میگیرد و قسمت دوم که متعاقباً توسط قسمت اول بارگذاری میشود.

|

||||

|

||||

بوتلودر باید محل ایمیج هسته را بر روی دیسک تعیین کرده و آن را در حافظه بارگذاری کند. همچنین ابتدا باید CPU را از [real mode] (ترجمه: حالت واقعی) 16 بیتی به [protected mode] (ترجمه: حالت محافظت شده) 32 بیتی و سپس به [long mode] (ترجمه: حالت طولانی) 64 بیتی سوییچ کند، جایی که ثباتهای 64 بیتی و کل حافظه اصلی در آن در دسترس هستند. کار سوم آن پرسوجو درباره اطلاعات خاص (مانند نگاشت حافظه) از BIOS و انتقال آن به هسته سیستم عامل است.

|

||||

|

||||

[real mode]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_mode

|

||||

[protected mode]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protected_mode

|

||||

[long mode]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_mode

|

||||

[memory segmentation]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X86_memory_segmentation

|

||||

|

||||

نوشتن بوتلودر کمی دشوار است زیرا به زبان اسمبلی و بسیاری از مراحل غیر بصیرانه مانند "نوشتن این مقدار جادویی در این ثبات پردازنده" نیاز دارد. بنابراین ما در این پست ایجاد بوتلودر را پوشش نمیدهیم و در عوض ابزاری به نام [bootimage] را ارائه میدهیم که بوتلودر را به طور خودکار به هسته شما اضافه میکند.

|

||||

|

||||

[bootimage]: https://github.com/rust-osdev/bootimage

|

||||

|

||||

اگر علاقهمند به ساخت بوتلودر هستید: با ما همراه باشید، مجموعهای از پستها در این زمینه از قبل برنامهریزی شده است! <!-- , check out our “_[Writing a Bootloader]_” posts, where we explain in detail how a bootloader is built. -->

|

||||

|

||||

#### استاندارد بوت چندگانه

|

||||

|

||||

برای جلوگیری از این که هر سیستم عاملی بوتلودر خود را پیادهسازی کند، که فقط با یک سیستم عامل سازگار است، [بنیاد نرم افزار آزاد] در سال 1995 یک استاندارد بوتلودر آزاد به نام [Multiboot] ایجاد کرد. این استاندارد یک رابط بین بوتلودر و سیستم عامل را تعریف میکند، به طوری که هر بوتلودر سازگار با Multiboot میتواند هر سیستم عامل سازگار با Multiboot را بارگذاری کند. پیادهسازی مرجع [GNU GRUB] است که محبوبترین بوتلودر برای سیستمهای لینوکس است.

|

||||

|

||||

[بنیاد نرم افزار آزاد]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_Software_Foundation

|

||||

[Multiboot]: https://wiki.osdev.org/Multiboot

|

||||

[GNU GRUB]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GNU_GRUB

|

||||

|

||||

برای سازگار کردن هسته با Multiboot، کافیست یک به اصطلاح [Multiboot header] را در ابتدای فایل هسته اضافه کنید. با این کار بوت کردن سیستم عامل در GRUB بسیار آسان خواهد شد. با این حال، GRUB و استاندارد Multiboot نیز دارای برخی مشکلات هستند:

|

||||

|

||||

[Multiboot header]: https://www.gnu.org/software/grub/manual/multiboot/multiboot.html#OS-image-format

|

||||

|

||||

- آنها فقط از حالت محافظت شده 32 بیتی پشتیبانی میکنند. این بدان معناست که شما برای تغییر به حالت طولانی 64 بیتی هنوز باید پیکربندی CPU را انجام دهید.

|

||||

- آنها برای ساده سازی بوتلودر طراحی شدهاند نه برای ساده سازی هسته. به عنوان مثال، هسته باید با [اندازه صفحه پیش فرض تنظیم شده] پیوند داده شود، زیرا GRUB در غیر اینصورت نمیتواند هدر Multiboot را پیدا کند. مثال دیگر این است که [اطلاعات بوت]، که به هسته منتقل میشوند، به جای ارائه انتزاعات تمیز و واضح، شامل ساختارها با وابستگی زیاد به معماری هستند.

|

||||

- هر دو استاندارد GRUB و Multiboot بصورت ناقص مستند شدهاند.

|

||||

- برای ایجاد یک ایمیج دیسکِ قابل بوت از فایل هسته، GRUB باید روی سیستم میزبان نصب شود. این امر باعث دشوارتر شدنِ توسعه در ویندوز یا Mac میشود.

|

||||

|

||||

[اندازه صفحه پیش فرض تنظیم شده]: https://wiki.osdev.org/Multiboot#Multiboot_2

|

||||

[اطلاعات بوت]: https://www.gnu.org/software/grub/manual/multiboot/multiboot.html#Boot-information-format

|

||||

|

||||

به دلیل این اشکالات ما تصمیم گرفتیم از GRUB یا استاندارد Multiboot استفاده نکنیم. با این حال، ما قصد داریم پشتیبانی Multiboot را به ابزار [bootimage] خود اضافه کنیم، به طوری که امکان بارگذاری هسته شما بر روی یک سیستم با بوتلودر GRUB نیز وجود داشته باشد. اگر علاقهمند به نوشتن هسته سازگار با Multiboot هستید، [نسخه اول] مجموعه پستهای این وبلاگ را بررسی کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

[نسخه اول]: @/edition-1/_index.md

|

||||

|

||||

### UEFI

|

||||

|

||||

(ما در حال حاضر پشتیبانی UEFI را ارائه نمیدهیم، اما خیلی دوست داریم این کار را انجام دهیم! اگر میخواهید کمک کنید، لطفاً در [ایشو گیتهاب](https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os/issues/349) به ما بگویید.)

|

||||

|

||||

## یک هسته مینیمال

|

||||

|

||||

اکنون که تقریباً میدانیم چگونه یک کامپیوتر بوت میشود، وقت آن است که هسته مینیمال خودمان را ایجاد کنیم. هدف ما ایجاد دیسک ایمیجی میباشد که “!Hello World” را هنگام بوت شدن چاپ کند. برای این منظور از [باینری مستقل Rust] که در پست قبل دیدید استفاده میکنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

همانطور که ممکن است به یاد داشته باشید، باینری مستقل را از طریق `cargo` ایجاد کردیم، اما با توجه به سیستم عامل، به نامهای ورودی و پرچمهای کامپایل مختلف نیاز داشتیم. به این دلیل که `cargo` به طور پیش فرض برای سیستم میزبان بیلد میکند، بطور مثال سیستمی که از آن برای نوشتن هسته استفاده میکنید. این چیزی نیست که ما برای هسته خود بخواهیم، زیرا منطقی نیست که هسته سیستم عاملمان را روی یک سیستم عامل دیگر اجرا کنیم. در عوض، ما میخواهیم هسته را برای یک _سیستم هدف_ کاملاً مشخص کامپایل کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

### نصب Rust Nightly

|

||||

|

||||

راست دارای سه کانال انتشار است: _stable_, _beta_, and _nightly_ (ترجمه از چپ به راست: پایدار، بتا و شبانه). کتاب Rust تفاوت بین این کانالها را به خوبی توضیح میدهد، بنابراین یک دقیقه وقت بگذارید و [آن را بررسی کنید](https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/appendix-07-nightly-rust.html#choo-choo-release-channels-and-riding-the-trains). برای ساخت یک سیستم عامل به برخی از ویژگیهای آزمایشی نیاز داریم که فقط در کانال شبانه موجود است، بنابراین باید نسخه شبانه Rust را نصب کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

برای مدیریت نصبهای Rust من به شدت [rustup] را توصیه میکنم. به شما این امکان را میدهد که کامپایلرهای شبانه، بتا و پایدار را در کنار هم نصب کنید و بروزرسانی آنها را آسان میکند. با rustup شما میتوانید از یک کامپایلر شبانه برای دایرکتوری جاری استفاده کنید، کافیست دستور `rustup override set nightly` را اجرا کنید. همچنین میتوانید فایلی به نام `rust-toolchain` را با محتوای `nightly` در دایرکتوری ریشه پروژه اضافه کنید. با اجرای `rustc --version` میتوانید چک کنید که نسخه شبانه را دارید یا نه. شماره نسخه باید در پایان شامل `nightly-` باشد.

|

||||

|

||||

[rustup]: https://www.rustup.rs/

|

||||

|

||||

کامپایلر شبانه به ما امکان میدهد با استفاده از به اصطلاح _feature flags_ در بالای فایل، از ویژگیهای مختلف آزمایشی استفاده کنیم. به عنوان مثال، میتوانیم [`asm!` macro] آزمایشی را برای اجرای دستورات اسمبلیِ اینلاین (تلفظ: inline) با اضافه کردن `[feature(asm)]!#` به بالای فایل `main.rs` فعال کنیم. توجه داشته باشید که این ویژگیهای آزمایشی، کاملاً ناپایدار هستند، به این معنی که نسخههای آتی Rust ممکن است بدون هشدار قبلی آنها را تغییر داده یا حذف کند. به همین دلیل ما فقط در صورت لزوم از آنها استفاده خواهیم کرد.

|

||||

|

||||

[`asm!` macro]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/unstable-book/library-features/asm.html

|

||||

|

||||

### مشخصات هدف

|

||||

|

||||

کارگو (کلمه: cargo) سیستمهای هدف مختلف را از طریق `target--` پشتیبانی میکند. سیستم هدف توسط یک به اصطلاح _[target triple]_ (ترجمه: هدف سه گانه) توصیف شده است، که معماری CPU، فروشنده، سیستم عامل، و [ABI] را شامل میشود. برای مثال، هدف سه گانه `x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu` یک سیستم را توصیف میکند که دارای سیپییو `x86_64`، بدون فروشنده مشخص و یک سیستم عامل لینوکس با GNU ABI است. Rust از [هدفهای سه گانه مختلفی][platform-support] پشتیبانی میکند، شامل `arm-linux-androideabi` برای اندروید یا [`wasm32-unknown-unknown` برای وباسمبلی](https://www.hellorust.com/setup/wasm-target/).

|

||||

|

||||

[target triple]: https://clang.llvm.org/docs/CrossCompilation.html#target-triple

|

||||

[ABI]: https://stackoverflow.com/a/2456882

|

||||

[platform-support]: https://forge.rust-lang.org/release/platform-support.html

|

||||

[custom-targets]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/rustc/targets/custom.html

|

||||

|

||||

برای سیستم هدف خود، به برخی از پارامترهای خاص پیکربندی نیاز داریم (به عنوان مثال، فاقد سیستم عامل زیرین)، بنابراین هیچ یک از [اهداف سه گانه موجود][platform-support] مناسب نیست. خوشبختانه Rust به ما اجازه میدهد تا [هدف خود][custom-targets] را از طریق یک فایل JSON تعریف کنیم. به عنوان مثال، یک فایل JSON که هدف `x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu` را توصیف میکند به این شکل است:

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

{

|

||||

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu",

|

||||

"data-layout": "e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

|

||||

"arch": "x86_64",

|

||||

"target-endian": "little",

|

||||

"target-pointer-width": "64",

|

||||

"target-c-int-width": "32",

|

||||

"os": "linux",

|

||||

"executables": true,

|

||||

"linker-flavor": "gcc",

|

||||

"pre-link-args": ["-m64"],

|

||||

"morestack": false

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

اکثر فیلدها برای LLVM مورد نیاز هستند تا بتواند کد را برای آن پلتفرم ایجاد کند. برای مثال، فیلد [`data-layout`] اندازه انواع مختلف عدد صحیح، مُمَیزِ شناور و انواع اشارهگر را تعریف میکند. سپس فیلدهایی وجود دارد که Rust برای کامپایل شرطی از آنها استفاده میکند، مانند `target-pointer-width`. نوع سوم فیلدها نحوه ساخت crate (تلفظ: کرِیت) را تعریف میکنند. مثلا، فیلد `pre-link-args` آرگومانهای منتقل شده به [لینکر] را مشخص میکند.

|

||||

|

||||

[`data-layout`]: https://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html#data-layout

|

||||

[لینکر]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linker_(computing)

|

||||

|

||||

ما همچنین سیستمهای `x86_64` را با هسته خود مورد هدف قرار میدهیم، بنابراین مشخصات هدف ما بسیار شبیه به مورد بالا خواهد بود. بیایید با ایجاد یک فایل `x86_64-blog_os.json` شروع کنیم (هر اسمی را که دوست دارید انتخاب کنید) با محتوای مشترک:

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

{

|

||||

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-none",

|

||||

"data-layout": "e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

|

||||

"arch": "x86_64",

|

||||

"target-endian": "little",

|

||||

"target-pointer-width": "64",

|

||||

"target-c-int-width": "32",

|

||||

"os": "none",

|

||||

"executables": true

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

توجه داشته باشید که ما OS را در `llvm-target` و همچنین فیلد `os` را به `none` تغییر دادیم، زیرا ما هسته را روی یک bare metal اجرا میکنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

همچنین موارد زیر که مربوط به ساخت (ترجمه: build-related) هستند را اضافه میکنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

"linker-flavor": "ld.lld",

|

||||

"linker": "rust-lld",

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

به جای استفاده از لینکر پیش فرض پلتفرم (که ممکن است از اهداف لینوکس پشتیبانی نکند)، ما از لینکر کراس پلتفرم [LLD] استفاده میکنیم که برای پیوند دادن هسته ما با Rust ارائه میشود.

|

||||

|

||||

[LLD]: https://lld.llvm.org/

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

"panic-strategy": "abort",

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

این تنظیم مشخص میکند که هدف از [stack unwinding] درهنگام panic پشتیبانی نمیکند، بنابراین به جای آن خود برنامه باید مستقیماً متوقف شود. این همان اثر است که آپشن `panic = "abort"` در فایل Cargo.toml دارد، پس میتوانیم آن را از فایل Cargo.toml حذف کنیم.(توجه داشته باشید که این آپشنِ هدف همچنین زمانی اعمال میشود که ما کتابخانه `هسته` را مجددا در ادامه همین پست کامپایل میکنیم. بنابراین حتماً این گزینه را اضافه کنید، حتی اگر ترجیح می دهید گزینه Cargo.toml را حفظ کنید.)

|

||||

|

||||

[stack unwinding]: https://www.bogotobogo.com/cplusplus/stackunwinding.php

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

"disable-redzone": true,

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

ما در حال نوشتن یک هسته هستیم، بنابراین بالاخره باید وقفهها را مدیریت کنیم. برای انجام ایمن آن، باید بهینهسازی اشارهگر پشتهای خاصی به نام _“red zone”_ (ترجمه: منطقه قرمز) را غیرفعال کنیم، زیرا در غیر این صورت باعث خراب شدن پشته میشود. برای اطلاعات بیشتر، به پست جداگانه ما در مورد [غیرفعال کردن منطقه قرمز] مراجعه کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

[غیرفعال کردن منطقه قرمز]: @/edition-2/posts/02-minimal-rust-kernel/disable-red-zone/index.md

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

"features": "-mmx,-sse,+soft-float",

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

فیلد `features` ویژگیهای هدف را فعال/غیرفعال میکند. ما ویژگیهای `mmx` و `sse` را با گذاشتن یک منفی در ابتدای آنها غیرفعال کردیم و ویژگی `soft-float` را با اضافه کردن یک مثبت به ابتدای آن فعال کردیم. توجه داشته باشید که بین پرچمهای مختلف نباید فاصلهای وجود داشته باشد، در غیر این صورت LLVM قادر به تفسیر رشته ویژگیها نیست.

|

||||

|

||||

ویژگیهای `mmx` و `sse` پشتیبانی از دستورالعملهای [Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD)] را تعیین میکنند، که اغلب میتواند سرعت برنامهها را به میزان قابل توجهی افزایش دهد. با این حال، استفاده از ثباتهای بزرگ SIMD در هسته سیستم عامل منجر به مشکلات عملکردی میشود. دلیل آن این است که هسته قبل از ادامه یک برنامهی متوقف شده، باید تمام رجیسترها را به حالت اولیه خود برگرداند. این بدان معناست که هسته در هر فراخوانی سیستم یا وقفه سخت افزاری باید حالت کامل SIMD را در حافظه اصلی ذخیره کند. از آنجا که حالت SIMD بسیار بزرگ است (512-1600 بایت) و وقفهها ممکن است اغلب اتفاق بیفتند، این عملیات ذخیره و بازیابی اضافی به طور قابل ملاحظهای به عملکرد آسیب میرساند. برای جلوگیری از این، SIMD را برای هسته خود غیرفعال میکنیم (نه برای برنامههایی که از روی آن اجرا می شوند!).

|

||||

|

||||

[Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD)]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIMD

|

||||

|

||||

یک مشکل در غیرفعال کردن SIMD این است که عملیاتهای مُمَیزِ شناور (ترجمه: floating point) در `x86_64` به طور پیش فرض به ثباتهای SIMD نیاز دارد. برای حل این مشکل، ویژگی `soft-float` را اضافه میکنیم، که از طریق عملکردهای نرمافزاری مبتنی بر اعداد صحیح عادی، تمام عملیات مُمَیزِ شناور را شبیهسازی میکند.

|

||||

|

||||

For more information, see our post on [disabling SIMD](@/edition-2/posts/02-minimal-rust-kernel/disable-simd/index.md).

|

||||

|

||||

#### کنار هم قرار دادن

|

||||

فایل مشخصات هدف ما اکنون به این شکل است:

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

{

|

||||

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-none",

|

||||

"data-layout": "e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

|

||||

"arch": "x86_64",

|

||||

"target-endian": "little",

|

||||

"target-pointer-width": "64",

|

||||

"target-c-int-width": "32",

|

||||

"os": "none",

|

||||

"executables": true,

|

||||

"linker-flavor": "ld.lld",

|

||||

"linker": "rust-lld",

|

||||

"panic-strategy": "abort",

|

||||

"disable-redzone": true,

|

||||

"features": "-mmx,-sse,+soft-float"

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### ساخت هسته

|

||||

|

||||

عملیات کامپایل کردن برای هدف جدید ما از قراردادهای لینوکس استفاده خواهد کرد (کاملاً مطمئن نیستم که چرا، تصور میکنم این فقط پیش فرض LLVM باشد). این بدان معنی است که ما به یک نقطه ورود به نام `start_` نیاز داریم همانطور که در [پست قبلی] توضیح داده شد:

|

||||

|

||||

[پست قبلی]: @/edition-2/posts/01-freestanding-rust-binary/index.md

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

// src/main.rs

|

||||

|

||||

#![no_std] // don't link the Rust standard library

|

||||

#![no_main] // disable all Rust-level entry points

|

||||

|

||||

use core::panic::PanicInfo;

|

||||

|

||||

/// This function is called on panic.

|

||||

#[panic_handler]

|

||||

fn panic(_info: &PanicInfo) -> ! {

|

||||

loop {}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

#[no_mangle] // don't mangle the name of this function

|

||||

pub extern "C" fn _start() -> ! {

|

||||

// this function is the entry point, since the linker looks for a function

|

||||

// named `_start` by default

|

||||

loop {}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

توجه داشته باشید که بدون توجه به سیستم عامل میزبان، باید نقطه ورود را `start_` بنامید.

|

||||

|

||||

اکنون میتوانیم با نوشتن نام فایل JSON بعنوان `target--`، هسته خود را برای هدف جدید بسازیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

> cargo build --target x86_64-blog_os.json

|

||||

|

||||

error[E0463]: can't find crate for `core`

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

شکست میخورد! این خطا به ما میگوید که کامپایلر Rust دیگر [کتابخانه `core`] را پیدا نمیکند. این کتابخانه شامل انواع اساسی Rust مانند `Result` ، `Option` و iterators است، و به طور ضمنی به همه کریتهای `no_std` لینک است.

|

||||

|

||||

[کتابخانه `core`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/core/index.html

|

||||

|

||||

مشکل این است که کتابخانه core همراه با کامپایلر Rust به عنوان یک کتابخانه _precompiled_ (ترجمه: از پیش کامپایل شده) توزیع میشود. بنابراین فقط برای میزبانهای سهگانه پشتیبانی شده مجاز است (مثلا، `x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu`) اما برای هدف سفارشی ما صدق نمیکند. اگر میخواهیم برای سیستمهای هدف دیگر کدی را کامپایل کنیم، ابتدا باید `core` را برای این اهداف دوباره کامپایل کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

#### آپشن `build-std`

|

||||

|

||||

اینجاست که [ویژگی `build-std`] کارگو وارد میشود. این امکان را میدهد تا بجای استفاده از نسخههای از پیش کامپایل شده با نصب Rust، بتوانیم `core` و کریت سایر کتابخانههای استاندارد را در صورت نیاز دوباره کامپایل کنیم. این ویژگی بسیار جدید بوده و هنوز تکمیل نشده است، بنابراین بعنوان «ناپایدار» علامت گذاری شده و فقط در [نسخه شبانه کامپایلر Rust] در دسترس میباشد.

|

||||

|

||||

[ویژگی `build-std`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/cargo/reference/unstable.html#build-std

|

||||

[نسخه شبانه کامپایلر Rust]: #installing-rust-nightly

|

||||

|

||||

برای استفاده از این ویژگی، ما نیاز داریم تا یک فایل [پیکربندی کارگو] در `cargo/config.toml.` با محتوای زیر بسازیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in .cargo/config.toml

|

||||

|

||||

[unstable]

|

||||

build-std = ["core", "compiler_builtins"]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

این به کارگو میگوید که باید `core` و کتابخانه `compiler_builtins` را دوباره کامپایل کند. مورد دوم لازم است زیرا یک وابستگی از `core` است. به منظور کامپایل مجدد این کتابخانهها، کارگو نیاز به دسترسی به کد منبع Rust دارد که میتوانیم آن را با `rustup component add rust-src` نصب کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

<div class="note">

|

||||

|

||||

**یادداشت:** کلید پیکربندی `unstable.build-std` به نسخهای جدیدتر از نسخه 2020-07-15 شبانه Rust نیاز دارد.

|

||||

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

|

||||

پس از تنظیم کلید پیکربندی `unstable.build-std` و نصب مولفه `rust-src`، میتوانیم مجددا دستور بیلد (کلمه: build) را اجرا کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

> cargo build --target x86_64-blog_os.json

|

||||

Compiling core v0.0.0 (/…/rust/src/libcore)

|

||||

Compiling rustc-std-workspace-core v1.99.0 (/…/rust/src/tools/rustc-std-workspace-core)

|

||||

Compiling compiler_builtins v0.1.32

|

||||

Compiling blog_os v0.1.0 (/…/blog_os)

|

||||

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.29 secs

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

میبینیم که `cargo build` دوباره `core` و `rustc-std-workspace-core` (یک وابستگی از `compiler_builtins`)، و کتابخانه `compiler_builtins` را برای سیستم هدف سفارشیمان کامپایل میکند.

|

||||

|

||||

#### موارد ذاتیِ مربوط به مموری

|

||||

|

||||

کامپایلر Rust فرض میکند که مجموعه خاصی از توابع داخلی برای همه سیستمها در دسترس است. اکثر این توابع توسط کریت `compiler_builtins` ارائه میشود که ما آن را به تازگی مجددا کامپایل کردیم. با این حال، برخی از توابع مربوط به حافظه در آن کریت وجود دارد که به طور پیشفرض فعال نیستند زیرا به طور معمول توسط کتابخانه C موجود در سیستم ارائه میشوند. این توابع شامل `memset` میباشد که مجموعه تمام بایتها را در یک بلوک حافظه بر روی یک مقدار مشخص قرار میدهد، `memcpy` که یک بلوک حافظه را در دیگری کپی میکند و `memcmp` که دو بلوک حافظه را با یکدیگر مقایسه میکند. اگرچه ما در حال حاضر به هیچ یک از این توابع برای کامپایل هسته خود نیازی نداریم، اما به محض افزودن کدهای بیشتر به آن، این توابع مورد نیاز خواهند بود (برای مثال، هنگام کپی کردن یک ساختمان).

|

||||

|

||||

از آنجا که نمیتوانیم به کتابخانه C سیستم عامل لینک دهیم، به روشی جایگزین برای ارائه این توابع به کامپایلر نیاز داریم. یک رویکرد ممکن برای این کار میتواند پیادهسازی توابع `memset` و غیره و اعمال صفت `[no_mangle]#` (برای جلوگیری از تغییر نام خودکار در هنگام کامپایل کردن) بر روی آنها اعمال باشد. با این حال، این خطرناک است زیرا کوچکترین اشتباهی در اجرای این توابع میتواند منجر به یک رفتار تعریف نشده شود. به عنوان مثال، ممکن است هنگام پیادهسازی `memcpy` با استفاده از حلقه `for` یک بازگشت بیپایان داشته باشید زیرا حلقههای `for` به طور ضمنی مِتُد تریتِ (کلمه: trait) [`IntoIterator::into_iter`] را فراخوانی میکنند، که ممکن است دوباره `memcpy` را فراخوانی کند. بنابراین بهتر است به جای آن از پیاده سازیهای تست شده موجود، مجدداً استفاده کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

[`IntoIterator::into_iter`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/core/iter/trait.IntoIterator.html#tymethod.into_iter

|

||||

|

||||

خوشبختانه کریت `compiler_builtins` از قبل شامل پیاده سازی تمام توابع مورد نیازمان است، آنها فقط به طور پیش فرض غیرفعال هستند تا با پیاده سازی های کتابخانه C تداخلی نداشته باشند. ما میتوانیم آنها را با تنظیم پرچم [`build-std-features`] کارگو بر روی `["compiler-builtins-mem"]` فعال کنیم. مانند پرچم `build-std`، این پرچم میتواند به عنوان پرچم `Z-` در خط فرمان استفاده شود یا در جدول `unstable` در فایل `cargo/config.toml.` پیکربندی شود. از آنجا که همیشه میخواهیم با این پرچم بیلد کنیم، گزینه پیکربندی فایل منطقیتر است:

|

||||

|

||||

[`build-std-features`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/cargo/reference/unstable.html#build-std-features

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in .cargo/config.toml

|

||||

|

||||

[unstable]

|

||||

build-std-features = ["compiler-builtins-mem"]

|

||||

```

|

||||

پشتیبانی برای ویژگی `compiler-builtins-mem` [به تازگی اضافه شده](https://github.com/rust-lang/rust/pull/77284)، پس حداقل به نسخه شبانه `2020-09-30` نیاز دارید.

|

||||

|

||||

در پشت صحنه، این پرچم [ویژگی `mem`] از کریت `compiler_builtins` را فعال میکند. اثرش این است که صفت `[no_mangle]#` بر روی [پیادهسازی `memcpy` و بقیه موارد] از کریت اعمال میشود، که آنها در دسترس لینکر قرار میدهد. شایان ذکر است که این توابع در حال حاضر [بهینه نشدهاند]، بنابراین ممکن است عملکرد آنها در بهترین حالت نباشد، اما حداقل صحیح هستند. برای `x86_64` ، یک pull request باز برای [بهینه سازی این توابع با استفاده از دستورالعملهای خاص اسمبلی][memcpy rep movsb] وجود دارد.

|

||||

|

||||

[ویژگی `mem`]: https://github.com/rust-lang/compiler-builtins/blob/eff506cd49b637f1ab5931625a33cef7e91fbbf6/Cargo.toml#L51-L52

|

||||

[پیادهسازی `memcpy` و بقیه موارد]: (https://github.com/rust-lang/compiler-builtins/blob/eff506cd49b637f1ab5931625a33cef7e91fbbf6/src/mem.rs#L12-L69)

|

||||

[بهینه نشدهاند]: https://github.com/rust-lang/compiler-builtins/issues/339

|

||||

[memcpy rep movsb]: https://github.com/rust-lang/compiler-builtins/pull/365

|

||||

|

||||

با این تغییر، هسته ما برای همه توابع مورد نیاز کامپایلر، پیاده سازی معتبری دارد، بنابراین حتی اگر کد ما پیچیدهتر باشد نیز باز کامپایل میشود.

|

||||

|

||||

#### تنظیم یک هدف پیش فرض

|

||||

|

||||

برای اینکه نیاز نباشد در هر فراخوانی `cargo build` پارامتر `target--` را وارد کنیم، میتوانیم هدف پیشفرض را بازنویسی کنیم. برای این کار، ما کد زیر را به [پیکربندی کارگو] در فایل `cargo/config.toml.` اضافه میکنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

[پیکربندی کارگو]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/config.html

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in .cargo/config.toml

|

||||

|

||||

[build]

|

||||

target = "x86_64-blog_os.json"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

این به `cargo` میگوید در صورتی که صریحاً از `target--` استفاده نکردیم، از هدف ما یعنی `x86_64-blog_os.json` استفاده کند. در واقع اکنون میتوانیم هسته خود را با یک `cargo build` ساده بسازیم. برای اطلاعات بیشتر در مورد گزینههای پیکربندی کارگو، [اسناد رسمی][پیکربندی کارگو] را بررسی کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

اکنون میتوانیم هسته را برای یک هدف bare metal با یک `cargo build` ساده بسازیم. با این حال، نقطه ورود `start_` ما، که توسط بوت لودر فراخوانی میشود، هنوز خالی است. وقت آن است که از طریق آن، چیزی را در خروجی نمایش دهیم.

|

||||

|

||||

### چاپ روی صفحه

|

||||

|

||||

سادهترین راه برای چاپ متن در صفحه در این مرحله [بافر متن VGA] است. این یک منطقه خاص حافظه است که به سخت افزار VGA نگاشت (مَپ) شده و حاوی مطالب نمایش داده شده روی صفحه است. به طور معمول از 25 خط تشکیل شده است که هر کدام شامل 80 سلول کاراکتر هستند. هر سلول کاراکتر یک کاراکتر ASCII را با برخی از رنگهای پیش زمینه و پس زمینه نشان میدهد. خروجی صفحه به این شکل است:

|

||||

|

||||

[بافر متن VGA]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VGA-compatible_text_mode

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

ما در پست بعدی، جایی که اولین درایور کوچک را برای آن مینویسیم، در مورد قالب دقیق بافر متن VGA بحث خواهیم کرد. برای چاپ “!Hello World”، فقط باید بدانیم که بافر در آدرس `0xb8000` قرار دارد و هر سلول کاراکتر از یک بایت ASCII و یک بایت رنگ تشکیل شده است.

|

||||

|

||||

پیادهسازی مشابه این است:

|

||||

|

||||

```rust

|

||||

static HELLO: &[u8] = b"Hello World!";

|

||||

|

||||

#[no_mangle]

|

||||

pub extern "C" fn _start() -> ! {

|

||||

let vga_buffer = 0xb8000 as *mut u8;

|

||||

|

||||

for (i, &byte) in HELLO.iter().enumerate() {

|

||||

unsafe {

|

||||

*vga_buffer.offset(i as isize * 2) = byte;

|

||||

*vga_buffer.offset(i as isize * 2 + 1) = 0xb;

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

loop {}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

ابتدا عدد صحیح `0xb8000` را در یک اشارهگر خام (ترجمه: raw pointer) میریزیم. سپس روی بایتهای [رشته بایت][byte string] [استاتیک][static] `HELLO` [پیمایش][iterate] میکنیم. ما از متد [`enumerate`] برای اضافه کردن متغیر درحال اجرای `i` استفاده میکنیم. در بدنه حلقه for، از متد [`offset`] برای نوشتن بایت رشته و بایت رنگ مربوطه استفاده میکنیم (`0xb` فیروزهای روشن است).

|

||||

|

||||

[iterate]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/book/ch13-02-iterators.html

|

||||

[static]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch10-03-lifetime-syntax.html#the-static-lifetime

|

||||

[`enumerate`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/core/iter/trait.Iterator.html#method.enumerate

|

||||

[byte string]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/tokens.html#byte-string-literals

|

||||

[اشارهگر خام]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/book/ch19-01-unsafe-rust.html#dereferencing-a-raw-pointer

|

||||

[`offset`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.pointer.html#method.offset

|

||||

|

||||

توجه داشته باشید که یک بلوک [`unsafe`] همیشه هنگام نوشتن در حافظه مورد استفاده قرار میگیرد. دلیل این امر این است که کامپایلر Rust نمیتواند معتبر بودن اشارهگرهای خام که ایجاد میکنیم را ثابت کند. آنها میتوانند به هر کجا اشاره کنند و منجر به خراب شدن دادهها شوند. با قرار دادن آنها در یک بلوک `unsafe`، ما در اصل به کامپایلر میگوییم که کاملاً از معتبر بودن عملیات اطمینان داریم. توجه داشته باشید که یک بلوک `unsafe`، بررسیهای ایمنی Rust را خاموش نمیکند. فقط به شما این امکان را میدهد که [پنج کار اضافی] انجام دهید.

|

||||

|

||||

[`unsafe`]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/book/ch19-01-unsafe-rust.html

|

||||

[پنج کار اضافی]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/book/ch19-01-unsafe-rust.html#unsafe-superpowers

|

||||

|

||||

می خواهم تأکید کنم که **این روشی نیست که ما بخواهیم در Rust کارها را از طریق آن پبش ببریم!** به هم ریختگی هنگام کار با اشارهگرهای خام در داخل بلوکهای ناامن بسیار محتمل و ساده است، به عنوان مثال، اگر مواظب نباشیم به راحتی میتوانیم فراتر از انتهای بافر بنویسیم.

|

||||

|

||||

بنابراین ما میخواهیم تا آنجا که ممکن است استفاده از `unsafe` را به حداقل برسانیم. Rust با ایجاد انتزاعهای ایمن به ما توانایی انجام این کار را میدهد. به عنوان مثال، ما میتوانیم یک نوع بافر VGA ایجاد کنیم که تمام کدهای ناامن را در خود قرار داده و اطمینان حاصل کند که انجام هرگونه اشتباه از خارج از این انتزاع _غیرممکن_ است. به این ترتیب، ما فقط به حداقل مقادیر ناامن نیاز خواهیم داشت و میتوان اطمینان داشت که [ایمنی حافظه] را نقض نمیکنیم. در پست بعدی چنین انتزاع ایمن بافر VGA را ایجاد خواهیم کرد.

|

||||

|

||||

[ایمنی حافظه]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memory_safety

|

||||

|

||||

## اجرای هسته

|

||||

|

||||

حال یک هسته اجرایی داریم که کار محسوسی را انجام میدهد، پس زمان اجرای آن فرا رسیده است. ابتدا، باید هسته کامپایل شده خود را با پیوند دادن آن به یک بوتلودر، به یک دیسک ایمیج قابل بوت تبدیل کنیم. سپس میتوانیم دیسک ایمیج را در ماشین مجازی [QEMU] اجرا یا با استفاده از یک درایو USB آن را بر روی سخت افزار واقعی بوت کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

### ساخت دیسک ایمیج

|

||||

|

||||

برای تبدیل هسته کامپایل شده به یک دیسک ایمیج قابل بوت، باید آن را با یک بوت لودر پیوند دهیم. همانطور که در [بخش مربوط به بوت شدن (لینک باید اپدیت شود)] آموختیم، بوت لودر مسئول مقداردهی اولیه پردازنده و بارگیری هسته میباشد.

|

||||

|

||||

[بخش مربوط به بوت شدن]: #the-boot-process

|

||||

|

||||

به جای نوشتن یک بوت لودر مخصوص خودمان، که به تنهایی یک پروژه است، از کریت [`bootloader`] استفاده میکنیم. این کریت بوتلودر اصلی BIOS را بدون هیچگونه وابستگی به C، فقط با استفاده از Rust و اینلاین اسمبلی پیاده سازی میکند. برای استفاده از آن برای راه اندازی هسته، باید وابستگی به آن را ضافه کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

[`bootloader`]: https://crates.io/crates/bootloader

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in Cargo.toml

|

||||

|

||||

[dependencies]

|

||||

bootloader = "0.9.8"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

افزودن بوتلودر به عنوان وابستگی برای ایجاد یک دیسک ایمیج قابل بوت کافی نیست. مشکل این است که ما باید هسته خود را با بوت لودر پیوند دهیم، اما کارگو از [اسکریپت های بعد از بیلد] پشتیبانی نمیکند.

|

||||

|

||||

[اسکریپت های بعد از بیلد]: https://github.com/rust-lang/cargo/issues/545

|

||||

|

||||

برای حل این مشکل، ما ابزاری به نام `bootimage` ایجاد کردیم که ابتدا هسته و بوت لودر را کامپایل میکند و سپس آنها را به یکدیگر پیوند میدهد تا یک ایمیج دیسک قابل بوت ایجاد کند. برای نصب ابزار، دستور زیر را در ترمینال خود اجرا کنید:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

cargo install bootimage

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

برای اجرای `bootimage` و ساختن بوتلودر، شما باید `llvm-tools-preview` که یک مولفه rustup میباشد را نصب داشته باشید. شما میتوانید این کار را با اجرای دستور `rustup component add llvm-tools-preview` انجام دهید.

|

||||

|

||||

پس از نصب `bootimage` و اضافه کردن مولفه `llvm-tools-preview`، ما میتوانیم یک دیسک ایمیج قابل بوت را با اجرای این دستور ایجاد کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

> cargo bootimage

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

میبینیم که این ابزار، هسته ما را با استفاده از `cargo build` دوباره کامپایل میکند، بنابراین به طور خودکار هر تغییری که ایجاد میکنید را دربر میگیرد. پس از آن بوتلودر را کامپایل میکند که ممکن است مدتی طول بکشد. مانند تمام کریتهای وابسته ، فقط یک بار بیلد میشود و سپس کش (کلمه: cache) میشود، بنابراین بیلدهای بعدی بسیار سریعتر خواهد بود. سرانجام، `bootimage`، بوتلودر و هسته شما را با یک دیسک ایمیج قابل بوت ترکیب میکند.

|

||||

|

||||

پس از اجرای این دستور، شما باید یک دیسک ایمیج قابل بوت به نام `bootimage-blog_os.bin` در مسیر `target/x86_64-blog_os/debug` ببینید. شما میتوانید آن را در یک ماشین مجازی بوت کنید یا آن را در یک درایو USB کپی کرده و روی یک سخت افزار واقعی بوت کنید. (توجه داشته باشید که این یک ایمیج CD نیست، بنابراین رایت کردن آن روی CD بیفایده است چرا که ایمیج CD دارای قالب متفاوتی است).

|

||||

|

||||

#### چگونه کار می کند؟

|

||||

|

||||

ابزار `bootimage` مراحل زیر را در پشت صحنه انجام می دهد:

|

||||

|

||||

- کرنل ما را به یک فایل [ELF] کامپایل میکند.

|

||||

- وابستگی بوتلودر را به عنوان یک اجرایی مستقل (ترجمه: standalone executable) کامپایل میکند.

|

||||

- بایتهای فایل ELF هسته را به بوتلودر پیوند میدهد.

|

||||

|

||||

[ELF]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executable_and_Linkable_Format

|

||||

[rust-osdev/bootloader]: https://github.com/rust-osdev/bootloader

|

||||

|

||||

وقتی بوت شد، بوتلودر فایل ضمیمه شده ELF را خوانده و تجزیه میکند. سپس بخشهای (ترجمه: segments) برنامه را به آدرسهای مجازی در جداول صفحه نگاشت (مپ) میکند، بخش `bss.` را صفر کرده و یک پشته را تنظیم میکند. در آخر، آدرس نقطه ورود (تابع `start_`) را خوانده و به آن پرش میکند.

|

||||

|

||||

### بوت کردن در QEMU

|

||||

|

||||

اکنون میتوانیم دیسک ایمیج را در یک ماشین مجازی بوت کنیم. برای راه اندازی آن در [QEMU]، دستور زیر را اجرا کنید:

|

||||

|

||||

[QEMU]: https://www.qemu.org/

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

> qemu-system-x86_64 -drive format=raw,file=target/x86_64-blog_os/debug/bootimage-blog_os.bin

|

||||

warning: TCG doesn't support requested feature: CPUID.01H:ECX.vmx [bit 5]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

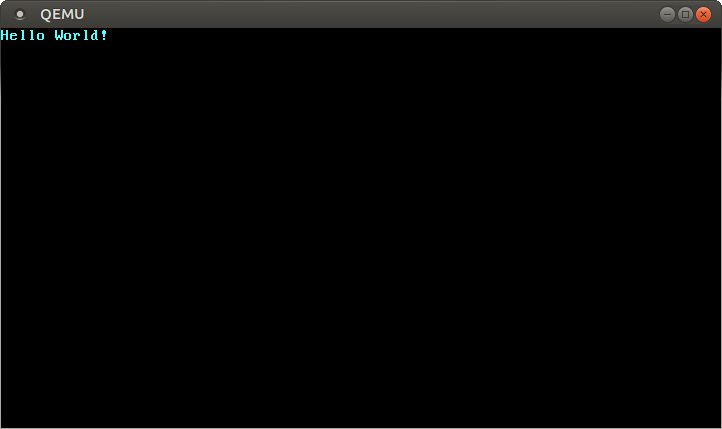

این یک پنجره جداگانه با این شکل باز میکند:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

میبینیم که “!Hello World” بر روی صفحه قابل مشاهده است.

|

||||

|

||||

### ماشین واقعی

|

||||

|

||||

همچنین میتوانید آن را بر روی یک درایو USB رایت و بر روی یک دستگاه واقعی بوت کنید:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

> dd if=target/x86_64-blog_os/debug/bootimage-blog_os.bin of=/dev/sdX && sync

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

در اینجا `sdX` نام دستگاه USB شماست. **مراقب باشید** که نام دستگاه را به درستی انتخاب کنید، زیرا همه دادههای موجود در آن دستگاه بازنویسی میشوند.

|

||||

|

||||

پس از رایت کردن ایمیج در USB، میتوانید با بوت کردن، آن را بر روی سخت افزار واقعی اجرا کنید. برای راه اندازی از طریق USB احتمالاً باید از یک منوی بوت ویژه استفاده کنید یا ترتیب بوت را در پیکربندی BIOS تغییر دهید. توجه داشته باشید که این در حال حاضر برای دستگاههای UEFI کار نمیکند، زیرا کریت `bootloader` هنوز پشتیبانی UEFI را ندارد.

|

||||

|

||||

### استفاده از `cargo run`

|

||||

|

||||

برای سهولت اجرای هسته در QEMU، میتوانیم کلید پیکربندی `runner` را برای کارگو تنظیم کنیم:

|

||||

|

||||

```toml

|

||||

# in .cargo/config.toml

|

||||

|

||||

[target.'cfg(target_os = "none")']

|

||||

runner = "bootimage runner"

|

||||

```

|

||||

جدول `'target.'cfg(target_os = "none")` برای همه اهدافی که فیلد `"os"` فایل پیکربندی هدف خود را روی `"none"` تنظیم کردهاند، اعمال میشود. این شامل هدف `x86_64-blog_os.json` نیز میشود. `runner` دستوری را که باید برای `cargo run` فراخوانی شود مشخص میکند. دستور پس از بیلد موفقیت آمیز با مسیر فایل اجرایی که به عنوان اولین آرگومان داده شده، اجرا میشود. برای جزئیات بیشتر به [اسناد کارگو][پیکربندی کارگو] مراجعه کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

دستور `bootimage runner` بصورت مشخص طراحی شده تا بعنوان یک `runner` قابل اجرا مورد استفاده قرار بگیرد. فایل اجرایی داده شده را به بوتلودر پروژه پیوند داده و سپس QEMU را اجرا میکند. برای جزئیات بیشتر و گزینههای پیکربندی احتمالی، به [توضیحات `bootimage`] مراجعه کنید.

|

||||

|

||||

[توضیحات `bootimage`]: https://github.com/rust-osdev/bootimage

|

||||

|

||||

اکنون میتوانیم از `cargo run` برای کامپایل هسته خود و راه اندازی آن در QEMU استفاده کنیم.

|

||||

|

||||

## مرحله بعد چیست؟

|

||||

|

||||

در پست بعدی، ما بافر متن VGA را با جزئیات بیشتری بررسی خواهیم کرد و یک رابط امن برای آن مینویسیم. همچنین پشتیبانی از ماکرو `println` را نیز اضافه خواهیم کرد.

|

||||

501

blog/content/edition-2/posts/02-minimal-rust-kernel/index.ja.md

Normal file

501

blog/content/edition-2/posts/02-minimal-rust-kernel/index.ja.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,501 @@

|

||||

+++

|

||||

title = "Rustでつくる最小のカーネル"

|

||||

weight = 2

|

||||

path = "ja/minimal-rust-kernel"

|

||||

date = 2018-02-10

|

||||

|

||||

[extra]

|

||||

chapter = "Bare Bones"

|

||||

# Please update this when updating the translation

|

||||

translation_based_on_commit = "7212ffaa8383122b1eb07fe1854814f99d2e1af4"

|

||||

# GitHub usernames of the people that translated this post

|

||||

translators = ["woodyZootopia", "JohnTitor"]

|

||||

+++

|

||||

|

||||

この記事では、Rustで最小限の64bitカーネルを作ります。前の記事で作った[フリースタンディングなRustバイナリ][freestanding Rust binary]を下敷きにして、何かを画面に出力する、ブータブルディスクイメージを作ります。

|

||||

|

||||

[freestanding Rust binary]: @/edition-2/posts/01-freestanding-rust-binary/index.ja.md

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- more -->

|

||||

|

||||

このブログの内容は [GitHub] 上で公開・開発されています。何か問題や質問などがあれば issue をたててください (訳注: リンクは原文(英語)のものになります)。また[こちら][at the bottom]にコメントを残すこともできます。この記事の完全なソースコードは[`post-02` ブランチ][post branch]にあります。

|

||||

|

||||

[GitHub]: https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os

|

||||

[at the bottom]: #comments

|

||||

[post branch]: https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os/tree/post-02

|

||||

|

||||

<!-- toc -->

|

||||

|

||||

## <ruby>起動<rp> (</rp><rt>Boot</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>のプロセス

|

||||

コンピュータを起動すると、マザーボードの [ROM] に保存されたファームウェアのコードを実行し始めます。このコードは、[<ruby>起動時の自己テスト<rp> (</rp><rt>power-on self test</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>][power-on self-test]を実行し、使用可能なRAMを検出し、CPUとハードウェアを<ruby>事前初期化<rp> (</rp><rt>pre-initialize</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>します。その後、<ruby>ブータブル<rp> (</rp><rt>bootable</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>ディスクを探し、オペレーティングシステムのカーネルを<ruby>起動<rp> (</rp><rt>boot</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>します。

|

||||

|

||||

[ROM]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/Read_only_memory

|

||||

[power-on self-test]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_On_Self_Test

|

||||

|

||||

x86には2つのファームウェアの標準規格があります:"Basic Input/Output System" (**[BIOS]**) と、より新しい "Unified Extensible Firmware Interface" (**[UEFI]**) です。BIOS規格は古く時代遅れですが、シンプルでありすべてのx86のマシンで1980年代からよくサポートされています。対して、UEFIはより現代的でずっと多くの機能を持っていますが、セットアップが複雑です(少なくとも私はそう思います)。

|

||||

|

||||

[BIOS]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_Input/Output_System

|

||||

[UEFI]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unified_Extensible_Firmware_Interface

|

||||

|

||||

今の所、このブログではBIOSしかサポートしていませんが、UEFIのサポートも計画中です。お手伝いいただける場合は、[GitHubのissue](https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os/issues/349)をご覧ください。

|

||||

|

||||

### BIOSの起動

|

||||

ほぼすべてのx86システムがBIOSによる起動をサポートしています。これは近年のUEFIベースのマシンも例外ではなく、それらはエミュレートされたBIOSを使います。前世紀のすべてのマシンにも同じブートロジックが使えるなんて素晴らしいですね。しかし、この広い互換性は、BIOSによる起動の最大の欠点でもあるのです。というのもこれは、1980年代の化石のようなブートローダーを動かすために、CPUが[<ruby>リアルモード<rp> (</rp><rt>real mode</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>][real mode]と呼ばれる16bit互換モードにされてしまうということを意味しているからです。

|

||||

|

||||

まあ順を追って見ていくこととしましょう。

|

||||

|

||||

コンピュータは起動時にマザーボードにある特殊なフラッシュメモリからBIOSを読み込みます。BIOSは自己テストとハードウェアの初期化ルーチンを実行し、ブータブルディスクを探します。ディスクが見つかると、 **<ruby>ブートローダー<rp> (</rp><rt>bootloader</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>** と呼ばれる、その先頭512バイトに保存された実行可能コードへと操作権が移ります。多くのブートローダーのサイズは512バイトより大きいため、通常は512バイトに収まる小さな最初のステージと、その最初のステージによって読み込まれる第2ステージに分けられています。

|

||||

|

||||

ブートローダーはディスク内のカーネルイメージの場所を特定し、メモリに読み込まなければなりません。また、CPUを16bitの[リアルモード][real mode]から32bitの[<ruby>プロテクトモード<rp> (</rp><rt>protected mode</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>][protected mode]へ、そして64bitの[<ruby>ロングモード<rp> (</rp><rt>long mode</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>][long mode]――64bitレジスタとすべてのメインメモリが利用可能になります――へと変更しなければなりません。3つ目の仕事は、特定の情報(例えばメモリーマップなどです)をBIOSから聞き出し、OSのカーネルに渡すことです。

|

||||

|

||||

[real mode]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/リアルモード

|

||||

[protected mode]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/プロテクトモード

|

||||

[long mode]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_mode

|

||||

[memory segmentation]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X86_memory_segmentation

|

||||

|

||||

ブートローダーを書くのにはアセンブリ言語を必要とするうえ、「何も考えずにプロセッサーのこのレジスタにこの値を書き込んでください」のような勉強の役に立たない作業がたくさんあるので、ちょっと面倒くさいです。ですのでこの記事ではブートローダーの制作については飛ばして、代わりに[bootimage]という、自動でカーネルの前にブートローダを置いてくれるツールを使いましょう。

|

||||

|

||||

[bootimage]: https://github.com/rust-osdev/bootimage

|

||||

|

||||

自前のブートローダーを作ることに興味がある人もご期待下さい、これに関する記事も計画中です!

|

||||

|

||||

#### Multiboot標準規格

|

||||

すべてのオペレーティングシステムが、自身にのみ対応しているブートローダーを実装するということを避けるために、1995年に[フリーソフトウェア財団][Free Software Foundation]が[Multiboot]というブートローダーの公開標準規格を策定しています。この標準規格では、ブートローダーとオペレーティングシステムのインターフェースが定義されており、Multibootに準拠したブートローダーであれば、同じくそれに準拠したすべてのオペレーティングシステムが読み込めるようになっています。そのリファレンス実装として、Linuxシステムで一番人気のブートローダーである[GNU GRUB]があります。

|

||||

|

||||

[Free Software Foundation]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/フリーソフトウェア財団

|

||||

[Multiboot]: https://wiki.osdev.org/Multiboot

|

||||

[GNU GRUB]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/GNU_GRUB

|

||||

|

||||

カーネルをMultibootに準拠させるには、カーネルファイルの先頭にいわゆる[Multiboot header]を挿入するだけで済みます。このおかげで、OSをGRUBで起動するのはとても簡単です。しかし、GRUBとMultiboot標準規格にはいくつか問題もあります:

|

||||

|

||||

[Multiboot header]: https://www.gnu.org/software/grub/manual/multiboot/multiboot.html#OS-image-format

|

||||

|

||||

- これらは32bitプロテクトモードしかサポートしていません。そのため、64bitロングモードに変更するためのCPUの設定は依然行う必要があります。

|

||||

- これらは、カーネルではなくブートローダーがシンプルになるように設計されています。例えば、カーネルは[通常とは異なるデフォルトページサイズ][adjusted default page size]でリンクされる必要があり、そうしないとGRUBはMultiboot headerを見つけることができません。他にも、カーネルに渡される[<ruby>ブート情報<rp> (</rp><rt>boot information</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>][boot information]は、クリーンな抽象化を与えてくれず、アーキテクチャ依存の構造を多く含んでいます。

|

||||

- GRUBもMultiboot標準規格もドキュメントが充実していません。

|

||||

- カーネルファイルからブータブルディスクイメージを作るには、ホストシステムにGRUBがインストールされている必要があります。これにより、MacとWindows上での開発は比較的難しくなっています。

|

||||

|

||||

[adjusted default page size]: https://wiki.osdev.org/Multiboot#Multiboot_2

|

||||

[boot information]: https://www.gnu.org/software/grub/manual/multiboot/multiboot.html#Boot-information-format

|

||||

|

||||

これらの欠点を考慮し、私達はGRUBとMultiboot標準規格を使わないことに決めました。しかし、あなたのカーネルをGRUBシステム上で読み込めるように、私達の[bootimage]ツールにMultibootのサポートを追加することも計画しています。Multiboot準拠なカーネルを書きたい場合は、このブログシリーズの[第1版][first edition]をご覧ください。

|

||||

|

||||

[first edition]: @/edition-1/_index.md

|

||||

|

||||

### UEFI

|

||||

|

||||

(今の所UEFIのサポートは提供していませんが、ぜひともしたいと思っています!お手伝いいただける場合は、 [GitHub issue](https://github.com/phil-opp/blog_os/issues/349)で教えてください。)

|

||||

|

||||

## 最小のカーネル

|

||||

どのようにコンピュータが起動するのかについてざっくりと理解できたので、自前で最小のカーネルを書いてみましょう。目標は、起動したら画面に"Hello, World!"と出力するようなディスクイメージを作ることです。というわけで、前の記事の[<ruby>独立した<rp> (</rp><rt>freestanding</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>Rustバイナリ][freestanding Rust binary]をもとにして作っていきます。

|

||||

|

||||

覚えていますか、この独立したバイナリは`cargo`を使ってビルドしましたが、オペレーティングシステムに依って異なるエントリポイント名とコンパイルフラグが必要なのでした。これは`cargo`は標準では **ホストシステム**(あなたの使っているシステム)向けにビルドするためです。例えばWindows上で走るカーネルというのはあまり意味がなく、私達の望む動作ではありません。代わりに、明確に定義された **ターゲットシステム** 向けにコンパイルできると理想的です。

|

||||

|

||||

### RustのNightly版をインストールする

|

||||

Rustには**stable**、**beta**、**nightly**の3つのリリースチャンネルがあります。Rust Bookはこれらの3つのチャンネルの違いをとても良く説明しているので、一度[確認してみてください](https://doc.rust-jp.rs/book-ja/appendix-07-nightly-rust.html)。オペレーティングシステムをビルドするには、nightlyチャンネルでしか利用できないいくつかの実験的機能を使う必要があるので、Rustのnightly版をインストールすることになります。

|

||||

|

||||

Rustの実行環境を管理するのには、[rustup]を強くおすすめします。nightly、beta、stable版のコンパイラをそれぞれインストールすることができますし、アップデートするのも簡単です。現在のディレクトリにnightlyコンパイラを使うようにするには、`rustup override set nightly`と実行してください。もしくは、`rust-toolchain`というファイルに`nightly`と記入してプロジェクトのルートディレクトリに置くことでも指定できます。Nightly版を使っていることは、`rustc --version`と実行することで確かめられます。表示されるバージョン名の末尾に`-nightly`とあるはずです。

|

||||

|

||||

[rustup]: https://www.rustup.rs/

|

||||

|

||||

nightlyコンパイラでは、いわゆる**feature flag**をファイルの先頭につけることで、いろいろな実験的機能を使うことを選択できます。例えば、`#![feature(asm)]`を`main.rs`の先頭につけることで、インラインアセンブリのための実験的な[`asm!`マクロ][`asm!` macro]を有効化することができます。ただし、これらの実験的機能は全くもって<ruby>不安定<rp> (</rp><rt>unstable</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>であり、将来のRustバージョンにおいては事前の警告なく変更されたり取り除かれたりする可能性があることに注意してください。このため、絶対に必要なときにのみこれらを使うことにします。

|

||||

|

||||

[`asm!` macro]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/unstable-book/library-features/asm.html

|

||||

|

||||

### ターゲットの仕様

|

||||

Cargoは`--target`パラメータを使ってさまざまなターゲットをサポートします。ターゲットはいわゆる[target <ruby>triple<rp> (</rp><rt>3つ組</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>][target triple]によって表されます。これはCPUアーキテクチャ、製造元、オペレーティングシステム、そして[ABI]を表します。例えば、`x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu`というtarget tripleは、`x86_64`のCPU、製造元不明、GNU ABIのLinuxオペレーティングシステム向けのシステムを表します。Rustは[多くのtarget triple][platform-support]をサポートしており、その中にはAndroidのための`arm-linux-androideabi`や[WebAssemblyのための`wasm32-unknown-unknown`](https://www.hellorust.com/setup/wasm-target/)などがあります。

|

||||

|

||||

[target triple]: https://clang.llvm.org/docs/CrossCompilation.html#target-triple

|

||||

[ABI]: https://stackoverflow.com/a/2456882

|

||||

[platform-support]: https://forge.rust-lang.org/release/platform-support.html

|

||||

[custom-targets]: https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/rustc/targets/custom.html

|

||||

|

||||

しかしながら、私達のターゲットシステムには、いくつか特殊な設定パラメータが必要になります(例えば、その下ではOSが走っていない、など)。なので、[既存のtarget triple][platform-support]はどれも当てはまりません。ありがたいことに、RustではJSONファイルを使って[独自のターゲット][custom-targets]を定義できます。例えば、`x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu`というターゲットを表すJSONファイルはこんな感じです。

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

{

|

||||

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu",

|

||||

"data-layout": "e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

|

||||

"arch": "x86_64",

|

||||

"target-endian": "little",

|

||||

"target-pointer-width": "64",

|

||||

"target-c-int-width": "32",

|

||||

"os": "linux",

|

||||

"executables": true,

|

||||

"linker-flavor": "gcc",

|

||||

"pre-link-args": ["-m64"],

|

||||

"morestack": false

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

ほとんどのフィールドはLLVMがそのプラットフォーム向けのコードを生成するために必要なものです。例えば、[`data-layout`]フィールドは種々の整数、浮動小数点数、ポインタ型の大きさを定義しています。次に、`target-pointer-width`のような、条件付きコンパイルに用いられるフィールドがあります。第3の種類のフィールドはクレートがどのようにビルドされるべきかを定義します。例えば、`pre-link-args`フィールドは[<ruby>リンカ<rp> (</rp><rt>linker</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>][linker]に渡される引数を指定しています。

|

||||

|

||||

[`data-layout`]: https://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html#data-layout

|

||||

[linker]: https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/リンケージエディタ

|

||||

|

||||

私達のカーネルも`x86_64`のシステムをターゲットとするので、私達のターゲット仕様も上のものと非常によく似たものになるでしょう。`x86_64-blog_os.json`というファイル(お好きな名前を選んでください)を作り、共通する要素を埋めるところから始めましょう。

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

{

|

||||

"llvm-target": "x86_64-unknown-none",

|

||||

"data-layout": "e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128",

|

||||

"arch": "x86_64",

|

||||

"target-endian": "little",

|

||||

"target-pointer-width": "64",

|

||||

"target-c-int-width": "32",

|

||||

"os": "none",

|

||||

"executables": true

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

<ruby>ベアメタル<rp> (</rp><rt>bare metal</rt><rp>) </rp></ruby>環境で実行するので、`llvm-target`のOSを変え、`os`フィールドを`none`にしたことに注目してください。

|

||||

|

||||

以下の、ビルドに関係する項目を追加します。

|

||||